Black Swan

Sub-Zero Sucker Punch

During the cold weeks that follow the winter holidays, a low-pressure warm front moves quickly into the New England region, along with a high-pressure Arctic cold front. The two masses collide, causing heavy rains that turn to ice by the time they reach the ground.

Layers of ice blanket an area from Maine to Maryland and as far west as Ohio, making it look like a world made of pure crystal.

Northeasterners shrug and hunker down for a few days of wild weather. A thinner layer of ice reaches west to St. Louis and south to Charlotte. Southeasterners grumble about the polar vortex interfering with their routine.

By the second day, trees fall and rooftops groan under the weight of nearly 3 inches of ice. Dozens of transmission towers buckle and collapse. Local power lines fall, pulling utility poles down across roadways.

Utility companies shift into crisis mode to assess the damage, which has plunged some homes and businesses into darkness. Utility crews from Georgia and Tennessee are dispatched to help get repair work underway, which is slowed by treacherous road conditions.

The worst, though, is yet to come.

Three days after the first storm hits, a second storm arrives, about 500 miles south. It wallops the Southeast and moves on up the Eastern seaboard, dropping another 2-plus inches of ice over two days. Heavy ice puts a death grip on everything from Memphis to Atlanta and on up through Washington, D.C.

The aging utility infrastructure can’t withstand the ice and winds. The fact that at least half of the Southeast’s utility workers had been deployed north makes matters worse — far worse. Four million customers in Georgia and Alabama alone are without power.

Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta is virtually paralyzed, stranding travelers and causing massive delays across the country. Gas stations shut down because pumps are inoperable.

Retailers with backup generators press on as long as they can, but shelves empty quickly of food and other essential goods. Some stores operate on a cash-only basis because payment systems are down.

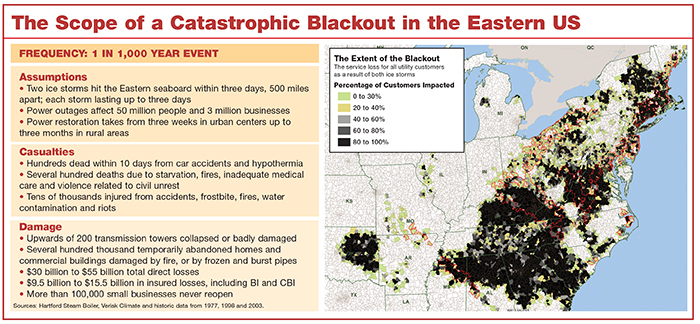

On the East Coast, more than 50 million people and 3 million businesses are without power. More than 200 transmission towers are badly damaged. Water supply across the entire East Coast is at risk, as treatment plants and pumping stations begin to lose backup power. Cell network circuits become congested, causing delays and weak signals. Some networks fail altogether.

Despite icy roads, millions leave their homes, seeking warmth and shelter. Some die from carbon monoxide poisoning or from blazes caused by open fires in their homes, attempting to keep warm. Many fires burn unchecked, resulting in widespread property damage.

Despite icy roads, millions leave their homes, seeking warmth and shelter. Some die from carbon monoxide poisoning or from blazes caused by open fires in their homes, attempting to keep warm. Many fires burn unchecked, resulting in widespread property damage.

States of emergency are declared for affected major cities. The National Guard is brought in to help clear roads, escort people to emergency shelters, and help maintain civil order among the increasingly frightened and desperate public.

Trees continue to fall for weeks, making power recovery achingly slow. It takes three to four weeks to get to 90 percent recovery for urban centers. Some outlying areas go without power for as long as three months.

Businesses struggle to reopen due to damage and lack of workers, as many have not returned to the area from wherever they sought shelter, or can’t get through to certain areas due to safety hazards.

Hundreds die from hypothermia, starvation, fires, auto accidents and small, localized riots. Tens of thousands more suffer injuries or become seriously ill. The very young, elderly and the poor are hardest hit.

No Escaping Loss

This scenario was created using the Blackout Risk Model, developed through a partnership of Hartford Steam Boiler and Verisk Climate, led by Robin Luo, vice president at HSB; Clifton Lancaster, senior risk analyst at HSB; and Kyle Beatty, president of Verisk Climate.

HSB and Verisk estimate that the frequency of each individual ice storm would be one in 150 years to 200 years. The two storms combined represent a frequency of one in 1,000 years or more.

This scenario loosely resembles a juxtaposition of two historic North American blackout events.

In January 1998, ice pummeled Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick for six straight days, destroying 130 transmission towers and leaving more than 4 million people without power — some for up to a month.

The insured losses from that storm totaled $1.6 billion, according to the Insurance Bureau of Canada. The total economic costs were estimated between $5 billion and $7 billion.

The second event occurred in August 2013, when a simple circuit overload led to cascading blackouts throughout North America, leaving 50 million people in the United States and Canada without power for up to six days. The estimated total economic cost of the outage was between $6 billion and $8 billion.

Combining the duration, ice load and frigid temperatures of the 1998 event with the coverage footprint of the 2013 event would result in a catastrophe exponentially more devastating than any blackout in North American history.

Some experts downplay the amount of property damage typical for an ice storm, but others say the level of property damage wouldn’t be far behind Hurricane Katrina or Superstorm Sandy.

Because of the duration of the power outage and the extreme volume of ice involved, homes and businesses left abandoned would likely succumb to frozen and bursting pipes. Collapsing roofs would lead to additional damage.

Overtaxed emergency responders likely wouldn’t be able to prevent damage caused by the inevitable looting and civil unrest. Fires started by those desperate for warmth could easily burn out of control, consuming neighboring properties in the process, especially in urban centers.

Contaminated water supplies would cause lasting problems that would take months to remedy. Lack of running water would create sanitation hazards.

Industries needing refrigeration, such as restaurants, supermarkets and pharmaceutical companies would suffer heavy losses. Manufacturing would also suffer due to a dependence on power and the difficulty and expense of temporarily relocating equipment.

Of course, that only scratches the surface of business income losses for companies up and down the East Coast, as well as key suppliers and customers across the country.

“Whether you’re impacted directly from the weather or indirectly, I don’t know how anyone escapes some sort of tragedy or economic loss from this,” said Wes Dupont, executive vice president and general counsel of Allied World Assurance Co. Holdings.

Even with power mostly restored in three to four weeks, there would be several more months of clean-up before normal operations resume. Some companies would have difficulty luring back clients that had switched suppliers in the interim.

Small businesses would no doubt be hard hit.

“Small to midsize companies, those that are not able to invest [in a standby power system] … they’re going to struggle,” said Mark Madar, director of risk management and regulatory compliance at CBIZ Risk & Advisory Services. “The companies that do not have a multi-location presence, especially your mom-and-pop types of businesses, they’re the ones who are going to take the hit here.”

But Lou Gritzo, FM Global’s vice president and research manager, said it would be a mistake to downplay the vulnerability of larger companies in this scenario.

“It’s the weakest link scenario,” said Gritzo. “The bigger effects are going to be these cascading failures where one or two pieces of the operation can’t recover and then the entire company experiences the consequences.

“That in turn affects other companies all over the country and all over the world. I think that’s where the biggest impact is going to be,” he said.

Mind the Gaps

For many companies, having a solid business interruption plan will make the difference in whether they make it through such a crisis. More than two in five (43 percent) businesses that experience a disaster and have no emergency plan don’t reopen, according to The Hartford. Of those that do reopen, only 29 percent are still operating two years later.

Even the most sophisticated disaster plan, however, will not shield companies from some degree of loss in an event of this magnitude. Unfortunately for some, the claims process is unlikely to be straightforward.

“The bigger effects are going to be these cascading failures where one or two pieces of the operation can’t recover and then the entire company experiences the consequences. That in turn affects other companies all over the country and all over the world.” —Lou Gritzo, vice president and research manager, FM Global

Blackouts can be a monkey wrench in the works. Companies may assume they’re covered for business losses in the event of a power outage because they have business interruption (BI) coverage — or time element coverage — on their property policies.

But in most cases, BI must be tied to physical damage to an insured’s assets. Several commercial property policies specifically exclude coverage resulting from a utility service interruption that originates away from the insured’s premises.

Standard BI coverage won’t be triggered for businesses that don’t suffer direct physical damage but were forced to close or relocate because of lack of employees or power, or orders from civil authorities to stay away due to safety hazards.

Some larger, sophisticated insurance buyers will have policies that include the necessary extensions needed to trigger the cover, but smaller firms may be left unprotected.

“I think [utility service interruption coverage] is spotty when it comes to small commercial businesses, who would need to ask for those extensions, as well as clients who are on standard boilerplate preprinted forms as opposed to a manuscripted form,” said Duncan Ellis, U.S. property practice leader for Marsh.

Another wording nuance to be aware of, he said, is that some language may provide for damage caused by a power outage, as in the case of a critical manufacturing load destroyed by loss of power in the middle of the process. But the BI side of the policy still may not have an extension for loss of income incurred after the outage.

Even for companies with the right coverage extensions, time durations vary. Some policies may not cover losses related to a service interruption that goes beyond a week or two. In general, many companies could find that their BI losses far exceed limits.

Insurers would see a high volume of contingent business interruption claims from those whose key customers or suppliers were compromised by the event. But the wording of CBI policies is similar to BI policies, and many insureds will find their coverage declaimed.

Companies with a regional base also may face push back from carriers on business income claims, said Mike LoGiudice, managing director of insurance and litigation support for CBIZ Valuation Group. “I might say, ‘I should have done [this amount of business] but for the property loss.’ ”

But the carriers may argue that regardless of damage, your customers would still be out of business themselves, so you wouldn’t have had any income. “They would take into effect the negative impact on your customers,” he said. “It would be a battle.”

____________________________________________________________________

Additional 2014 black swan stories:

When the 8.5 magnitude earthquake hits, sea water will devastate much of Los Angeles and San Francisco, and a million destroyed homes will create a failed mortgage and public sector revenue tsunami.

When a nuclear reactor melts down due to a powerful tornado, deadly contamination rains down on a metropolitan area.