Black Swan

Bigger Than the Big One

When it starts at 2:12 p.m. on an October Thursday, residents of California old enough to remember previous big quakes assure themselves that they’ve been through this before.

But in another 10 seconds or so, they see that they are profoundly wrong.

The shaking, stronger than anything ever measured in the United States, goes on and on, not for seconds, but for minutes. Panic builds to horror as people are thrown to the ground, stoned by debris from crumbling office buildings or crushed in their cars under collapsed freeway overpasses.

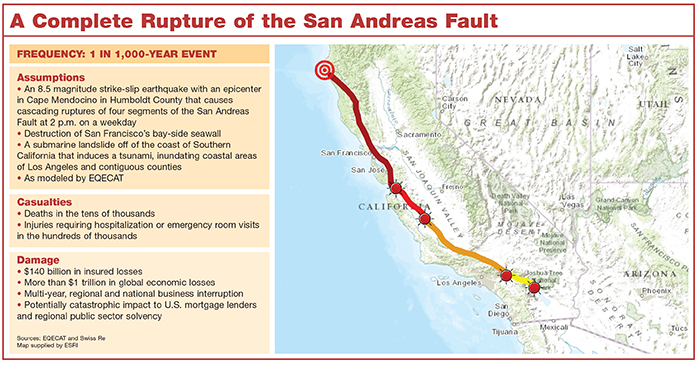

This is a quake even bigger than “The Big One,” which modelers tend to peg as something in the 7.6 to 8.0 range on the Richter scale. This is an 8.5 magnitude quake on the San Andreas Fault with an epicenter at Cape Mendocino in Humboldt County, about 250 miles north of San Francisco.

According to modeling firm EQECAT, a subsidiary of CoreLogic, the rupture in Humboldt County triggers a cascade of four contiguous San Andreas Fault segment ruptures that end in Southern California at Indio in the Salton Sea.

It was fire that destroyed much of San Francisco in the legendary 1906 earthquake, but it is salt water this time that plays a substantial role in the undoing of that great city and its bigger cousin, Los Angeles.

In Southern California, the quake provokes a submarine landslide, 100 miles or so in length and miles wide, that runs from the coastal waters of Santa Barbara down to San Luis Rey in San Diego County.

That immense shifting of underwater soil in turn pushes water toward land in a tsunami that runs a mile or so inland in places, damaging large oil refineries in El Segundo and Torrance, and creating an environmental disaster.

Hundreds of billions of dollars of Southern California’s high-priced residential and commercial real estate is erased in 10 minutes. Thousands die within that same time span.

The Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach, the two biggest U.S. container ports, are shut down, severely damaged by the shaking and the tsunami.

To the north, the “Achilles heel” of San Francisco, its bay-side seawall, ruptures in multiple places, spilling bay water into the city.

The four-mile seawall, which runs from Hyde Street and Fisherman’s Wharf in the north to Pier 54 and Channel Street in the south, was cobbled together in 21 sections from 1878 to 1924. The land mass filled in behind the seawall is composed of sand, clay and gravel in places and liquefies under a quake of this magnitude, undermining the city’s Embarcadero roadway and severing crucial utility and public transportation connections.

San Francisco is far better prepared for seismic activity than any U.S. city. But when the seawall fails, the surging bay water undermines downtown office buildings already weakened by the shaking, and several of them collapse.

The destruction of the seawall shuts down the Transbay Tube, the underwater Bay Area Rapid Transit rail connection between San Francisco and Oakland, stranding hundreds of thousands of commuters in the broken cities.

Damage to the Bay Bridge shuts down first-responder access from the east. Damage to the Golden Gate Bridge cuts off aid from the north.

With emergency responders in the rest of the state frantically working to save their own populations, the city is sealed off from help, stricken and flood ravaged. Its residents tend to the injured and dying as best they can as spiraling smoke obscures the sun and sirens wail unceasingly.

The Fallout

According to EQECAT, the insured losses from a cascading San Andreas rupture measuring 8.5 on the Richter scale would amount to $140 billion.

Before the Tohoku quake of March 2011, scientists thought that an 8.5 on the San Andreas was inconceivable, according to Mahmoud Khater, chief science and technology officer with EQECAT. But before Tohoku, no one thought that the fault in Japan could produce a 9.0. The most it was thought capable of was an 8.4.

Tragically, the world now knows better, after more than 16,000 Japanese deaths and more than $30 billion in insured losses.

“It is really Tohoku that has altered the scientific and actuarial thinking,” Khater said.

The importance of the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles to trade with technology suppliers in Asia is just one piece of the extended business interruption and contingent business interruption aftermath of an 8.5 on the San Andreas that would lead to global economic losses of $1 trillion.

“We clearly agree that it would be a multi-year event,” said Jamie Miller, head of North American property for Swiss Re.

EQECAT estimates that there is $2.2 trillion in residential and commercial property exposure in California. The company said fatalities from the event we envision would run into the tens of thousands.

As gruesome as tens of thousands of deaths would be, and as daunting to the insurance industry as $140 billion in insured losses may appear, Miller and his colleagues at Swiss Re fear that even greater economic calamity awaits, should this event occur.

Alex Kaplan, vice president, global partnerships, public sector business with Swiss Re, points to the low take-up rate of personal lines earthquake insurance in California, the weak financial condition of the federal and local governments, and how that combination could balloon into a national economic calamity.

“You talk about firefighting and other ongoing expenses that aren’t passed on through insurance, coupled with less homeowners to pay for it. That to me is the black swan.” — Jamie Miller, head of North American property, Swiss Re

Consider, under Kaplan’s direction, that only 12 percent of homeowners in California carry earthquake insurance.

Modelers say 1 million homes would be severely damaged in the 8.5 quake.

“That’s 880,000 homes that are uninsured and 660,000 of those homes have mortgages,” Kaplan said.

Not only will there be hundreds of billions of dollars in damage but as a result of the earthquake, the rate of mortgage defaults and credit losses in California will spike, he said.

“Keep in mind that California has one-sixth of all underwater mortgages,” he added.

In addition, the federal government will be unable to sufficiently bail out local governments in California, which will suffer greatly reduced property tax collections just as public services such as police and fire protection are stretched to the limit.

“FEMA’s current funding scheme is inadequate to handle something like this,” Kaplan said.

From 2005 through 2011, the agency’s average disaster appropriation was $1.75 billion per year, Kaplan said. But spending on supplemental appropriations amounted to an average of $4.6 billion per year.

“There is no probabilistic modeling that goes into how the federal government allocates funds,” Kaplan said.

“You talk about firefighting and other ongoing expenses that aren’t passed on through insurance, coupled with less homeowners to pay for it,” Miller said.

“That to me is the black swan.”

Mitigation and Recovery

For years — since the Loma Prieta quake that struck the Bay Area in 1989, and the Northridge quake that hit Los Angeles in 1994 — governments in California have taken aggressive measures to limit the damage that would occur in a major quake and to make California cities more resilient.

In April, with a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, San Francisco appointed the world’s first Chief Resiliency Officer, Patrick Otellini. The Rockefeller program will eventually fund 100 such positions worldwide.

“We have a mentality that we need to get over and that is we are the biggest country in the world with the deepest capital markets and The Big One wouldn’t be that big of a deal. I don’t think that’s true.” — Alex Kaplan, vice president, Swiss Re

In the new position, Otellini is putting to work his 10 years of experience in the private sector helping businesses negotiate the City of San Francisco’s permitting and code requirements process and his more recent job, which he still holds, as the director of the city’s Earthquake Implementation Program.

The host of initiatives he is working on include measuring the vulnerability of the city’s seawall and creating a plan to improve it, coordinating the various utilities whose services the city depends on to increase their post-disaster resiliency, and implementation of a program designed to speed up occupancy of hotels and other businesses post-quake provided they have been inspected by city-approved engineers.

Under Otellini’s direction, the city’s Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance last year that required owners to retrofit and make more earthquake-proof rental properties with wood frame construction, built before 1978, and having five or more residential units with two or more stories over a “soft story” — a story with large open spaces like a garage or retail space with large windows.

The city’s experience in 1989 told it that housing stock would be totally destroyed should The Big One hit.

Otellini said there are 60,000 residents living in rent-controlled housing who would lose that protection in a big quake had the city not taken action.

“Not to mention the impact on our city services and the fact that these buildings tend to be very defining of the architecture of San Francisco,” he said.

Although it’s not regulating a big piece of the city’s overall commercial and residential building stock, the measure is an example of how governments can begin to pick off lower hanging fruit and make their cities incrementally more resilient.

The Los Angeles City Council took note of the San Francisco measure and passed its own ordinance. The two city governments are now working together on a number of resiliency initiatives and to make state politicians more aware of what else needs to be done.

“I am very excited about that dialogue,” Otellini said.

The efforts of Otellini and others will lessen the cost of The Big One and bring businesses and communities back quicker, said Swiss Re’s Kaplan.

“I am very impressed with how public entities from the city level, to the state level, to the federal level are thinking about the physical resilience of a particular region,” Kaplan said.

“How do you retrofit the buildings, how do you communicate the risk, and they have done a tremendous job of enhancing that over the years,” he said.

“What I am still concerned about is the financial resilience, how are you going to fund these losses?” he asked.

Kaplan said he now sees U.S. cities taking a much more engaged approach to which insurance or insurance-linked securities solutions could help to remove the volatility from public sector balance sheets in the case of a disaster.

“The Mexican government is highly sophisticated in that regard and we see it is starting to happen in the U.S.,” Kaplan said.

“We have a mentality that we need to get over and that is we are the biggest country in the world with the deepest capital markets and The Big One wouldn’t be that big of a deal,” Kaplan said.

“I don’t think that’s true.”

____________________________________________________________________

Additional 2014 black swan stories:

When a nuclear reactor melts down due to a powerful tornado, deadly contamination rains down on a metropolitan area.

A double dose of ice storms batter the Eastern seaboard, plunging 50 million people and three million businesses into a polar vortex of darkness and desperation.