Black Swan

Toxic Tornado

It is a warm, humid spring day in Dallas/Fort Worth when strong thunderstorms begin to develop alongside a high-altitude weather system that includes strong winds and convective energy coming from the Rocky Mountains.

By mid-afternoon, the atmosphere reaches a tipping point. A massive supercell thunderstorm along the weather front produces large, damaging hail and what is later designated as an EF5 tornado, with winds in excess of 200 mph.

The most recent tornado of this size as designated by the National Weather Service was on May 20, 2013, when an EF5 struck Moore, Okla., killing 24 people, flattening neighborhoods and schools, and injuring more than 350 people.

This Texas tornado is much, much worse.

Video: An EF5 tornado in May 2013 flattened much of Moore, Okla.

Moving in the usual southwest to northeast direction, it creates a damage path about 1 mile wide and nearly 200 miles long, and directly strikes the Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant in Glen Rose, Texas, about 40 miles west of Fort Worth and 60 miles west of Dallas.

The power plant’s reactor was built to withstand winds up to 300 mph, but it can’t withstand what happens after the tornado throws around multiple gas-filled tanker trucks, which explode and kill numerous workers.

Matthew Nielsen, director of Americas product management at RMS, created the model for our Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant black swan scenario.

Debris fills the air as the powerful winds destroy much of the plant’s emergency equipment, making it impossible to maintain proper conditions and temperature within the reactor. The remaining power plant workers feverishly try to manually shut down the nuclear reactor before it melts down. They can’t.

When the reactor’s heat exceeds the ability of the plant’s processes to cool it down, radioactive gases begin to snake their way into the funnel stacks. The radioactive contamination is carried by the ferocious winds directly toward Dallas/Fort Worth.

Communication fails as area power lines go down, so it is difficult to warn the 7 million residents of the Metroplex, as Dallas/Fort Worth is known. Residents know the tornado has been sighted and try to prepare, but they don’t know that deadly airborne toxins are being carried toward them.

The Damage

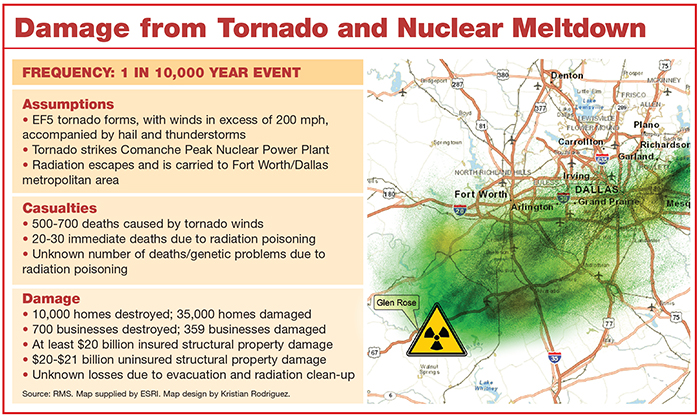

About 10,000 homes and 700 commercial structures in the direct path of the tornado are completely destroyed and another 35,000 suffer damage, according to a model built by RMS. Roofs are ripped off apartment houses and multi-family dwellings. Vehicles are tossed around like toys, and with the storm striking at rush hour, workers on the roads are exposed to flying debris and high winds.

Even with residents sheltering in basements and safe rooms, fatalities reach into the 500-700 range — putting this event in line to be the deadliest tornado in U.S. history, after the Tri-State tornado of 1925, which killed 695 people in Missouri, Illinois and Indiana.

But it is the unseen radioactive contamination that ultimately makes the deadliest mark on the area.

Immediate fatalities from radiation poisoning number about two dozen, but as the contaminated rainfall seeps into the ground soil and water supply, the long-term health of the residents — and their descendants — is jeopardized. So, too, are the cattle and other agricultural products of Texas, which leads the nation in the number of ranches and farms it holds.

Chernobyl and Fukushima are the only events of a similar nature, even though the United States has seen its own recent near misses.

The radioactivity causes large swaths of area to be cordoned off, making it difficult to repair transmission and power lines as well as homes and businesses.

“The hard truth is that many businesses will close and many people will move from the area,” said Todd Macumber, president of international risk services, Hub International.

Chernobyl and Fukushima are the only events of a similar nature, even though the United States has seen its own recent near misses.

In 2011, a tornado knocked out power to the Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant near Huntsville, Ala., requiring the shut down of its three reactors. The plant fired up backup diesel generators until power was restored. The storm also disabled the plant’s sirens, which are needed to warn nearby residents in a crisis.

That same year, a tornado barely missed damaging 2.5 million pounds of radioactive waste at the Surrey Power Station in southeastern Virginia, although it touched down in the plant’s electrical switchyard and disabled power to the cooling pumps. The operators needed to activate backup diesel generators to run the two reactors until power was restored.

Twenty-eight years after the radioactive disaster at Chernobyl in 1986, some parts of the Ukraine remain a toxic wasteland. And in Japan, an initial evacuation area of about 2 miles surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was soon widened to about 12.5 miles.

About 300 tons of highly radioactive water has leaked from storage tanks at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station.

Now, three years after three of Fukushima’s six reactors melted down, the area is still unlivable and 40 miles away, diagnoses in children of thyroid cancer, which is caused by radiation poisoning, are skyrocketing, according to some reports.

Nearly 16,000 people died in the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan, causing the meltdown. About 160,000 people were evacuated, 130,000 buildings were destroyed and $210 billion in damage was sustained.

The Texas scenario has a lot of variables, said Matthew Nielsen, director of Americas product management at RMS, who created the model for our Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant black swan scenario.

The likelihood of a tornado, with thunderstorms and hail, causing massive structural damage is about 1 in 200 years, he said. Such an event would result in at least $20 billion in insured losses and uninsured losses of about the same amount.

But a tornado following the exact path as this scenario — striking the power plant and heading into the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex — has a much, much smaller chance — about 1 in 10,000 years.

“Given the fact that tornadoes are very rare, it isn’t something that I think people should be screaming and running around frantically about,” Nielsen said. “But it’s certainly something that could happen.”

As for losses due to the radiation? “There’s not a lot of historical data points that we can confidently say that that portion would be x or y billion,” he said.

The Recovery

Any rebuilding will be delayed by the threat posed by radioactive contamination, which may spread over a large area via the thunderstorms and storm water runoff.

From an insurance perspective, all personal and commercial lines of insurance have a nuclear energy hazard exclusion. American Nuclear Insurers (ANI) provides third-party liability insurance for all power reactors in the United States.

“We are responsible for the insurance coverage protecting the operators from claims alleging bodily injury or property damage offsite from [radioactive] materials,” said Michael Cass, vice president and general counsel at ANI, a joint underwriting association with 20 insurance company members.

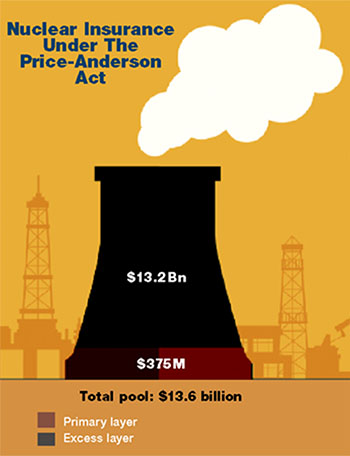

The ANI was created under the Price-Anderson Act of 1957 and provides a primary policy limit of $375 million for claims due to offsite consequences from the release of radioactive materials from the 100 operating nuclear power plants in the United States. It also covers some plants that are shut down or in the process of being decommissioned, he said.

The ANI was created under the Price-Anderson Act of 1957 and provides a primary policy limit of $375 million for claims due to offsite consequences from the release of radioactive materials from the 100 operating nuclear power plants in the United States. It also covers some plants that are shut down or in the process of being decommissioned, he said.

The ANI also covers costs related to emergency response and evacuation, including food, clothing and shelter, he said.

The joint underwriting association also administers an additional excess layer of about $13.2 billion, the costs of which would be borne by the power plant operators, and would be apportioned equally among them.

For any claims above $13.6 billion (which includes both the primary and excess layers), the Price-Anderson Act requires the U.S. Congress to “take steps to come up with a scheme to provide full compensation to the public and to continue claims payments,” Cass said.

“They could assess or tax the energy industry in some fashion or form. It doesn’t say that specifically, but that is what is alluded to.”

None of the insurance companies that are ANI members would be adversely affected if such a black swan event were to occur, he said.

“There would be a loss reserve recorded on their balance sheets, per participation in our pool, but we do have funds set aside for these catastrophic events where we wouldn’t be requiring any additional funds,” Cass said.

Damage to the power plant itself would be covered by Nuclear Electric Insurance Ltd., which insures electric utilities and energy companies in the United States. Current limits are $1.5 billion per site on the primary program, and up to $1.5 billion per site in its excess program.

Allan Koenig, vice president, corporate communications at Energy Future Holdings, which operates Comanche Peak, said the plant is robustly protected. It has two independent systems that can provide off-site power as well as backup diesel generators, to allow the units to be safety shut down in the event of natural catastrophes.

He also noted the plant has safety shields for fuel storage casks, a 45-inch-thick steel-reinforced concrete containment building wall, and fire protection redundancies.

As for the affected businesses and homeowners, they may be left in a swirling vortex of coverage confusion. The situation would have the flavor of what happened after Superstorm Sandy, when coverage often depended on whether damage was caused by flooding or wind surge.

The question for Texas insureds would be whether the damage was caused by the tornado or by the radioactivity.

“It’s an incredibly complex question and a complex issue that is really only solvable and resolvable if and when the incident occurs,” said John Butler, vice president of the environmental practice at Hub International.

“What it boils down to is the chicken and the egg scenario,” he said. “What came first? Either event has the ability on its own to create a total loss.”

Resilience and redundancy should be the key takeaways from this, said Peter Boynton, founding co-director of the Kostas Research Institute for Homeland Security at Northeastern University in suburban Boston.

“If we can retain a percentage of the critical function of whatever system we are talking about, the difference between 0 percent and 30 percent when the bad thing happens is huge.” — Peter Boynton, founding co-director of the Kostas Research Institute for Homeland Security, Northeastern University

Instead of viewing catastrophic events from an emergency management perspective, where the discussion revolves around what was — or was not — managed well, it’s better to look at the way design can lead to “continuity of function,” he said.

When Boynton was head of emergency management for the state of Connecticut, he managed the statewide response in 2011 to Hurricane Irene, which knocked out 70 percent of the state’s electric grid, leaving residents unable to access many gas stations, ATMs and grocery stores.

If the state had designed a “resiliency approach” prior to the event, it could have built in a pre-determined amount of redundancy into the system so that, say, an additional 20 percent or 30 percent of the grid remained viable.

“If we can retain a percentage of the critical function of whatever system we are talking about, the difference between 0 percent and 30 percent when the bad thing happens is huge,” Boynton said.

In the Texas scenario, if the crisis planning included a redundancy for warning nearby residents even when the power and communication lines failed — such as by using satellites to create a minimal level of continuity — the amount of death and destruction could have been lessened.

“Otherwise, we really are setting ourselves up for an impossible discussion,” he said. “You can’t just pick up these pieces at the moment of crisis. You have to understand how system design can play a role.”

Analyzing such a black swan scenario is a useful exercise, said Justin VanOpdorp, manager, quantitative analysis, at Lockton.

“Can this actually happen? Yes. Will it? Maybe not,” he said. “I think what it does is, it helps to think through it just to be prepared for those situations when they do arise.”

____________________________________________________________________

Additional 2014 black swan stories:

When the 8.5 magnitude earthquake hits, sea water will devastate much of Los Angeles and San Francisco, and a million destroyed homes will create a failed mortgage and public sector revenue tsunami.

A double dose of ice storms batter the Eastern seaboard, plunging 50 million people and three million businesses into a polar vortex of darkness and desperation.