15 Things You Must Know About Insuring Mega-Projects: The Core Insurance Instruments

The skyline of San Francisco, whose Millennium Tower is allegedly still sinking.

America has entered the era of the “mega project.” While the term is notably rather loose in industry definition, it generally refers to projects in excess of $1 billion and encompasses large-scale infrastructure work, such as airports, bridges, tunnels and highway systems, power and rail, to commercial use structures like skyscrapers and hospital complexes.

This is the second part in a three-part series. As highlighted in Part One, case studies on the Orlando International Airport (OIA) and the Los Angeles World Airport (LAWA) both show relevancy as we continue to discuss the 15 things you should know about risk and insurance before taking on a construction project of this magnitude.

(For items 1-4, see Part One.)

5) Owner Required Insurance

Generally, the contractor or prime contracting entity carries two primary forms of insurance coverage: commercial general liability (CGL), which provides coverage for bodily injury and property damage from a covered loss, and professional liability, which covers errors and omissions in the performance of professional services, such as design, engineering and some forms of consulting and construction management.

Most mega-projects also include ancillary coverage, such as automobile, workers’ compensation and other specialty lines of insurance, which may be applicable to the project, like pollution for example.

Often the CGL coverage is rolled into a more comprehensive insurance program called a “wrap,” or more formally, a contractor control insurance program (CCIP). A CCIP provides CGL and excess coverage for the contractor and enrolled subcontractors and suppliers and typically rolls in the ancillary policies.

6) Commercial General Liability

A textbook definition of CGL coverage is “a standard insurance policy issued to business organizations to protect them against liability claims for bodily injury and property damage arising out of premises, operations, products and completed operations.” Contrary to the expectation of many owners and even industry professionals, a CGL does not provide coverage for construction defects.

While courts vary on this point, at best a CGL policy provides coverage for damages flowing from a covered loss, like subcontractor defective work for example.

Sarah Guo, associate

construction law and litigation group, Nelson Mullins Broad and Cassel

The archetype example for this key distinction is a simple window leak case where the leaking arises from defective installation by a subcontractor. If the leak causes damage to property, (say carpeting, finishes and perhaps contents of the building), there generally is insurance coverage for this ensuing damage. If the leaks are caught before damages ensue, the cost to repair the defective window installation is not covered by the CGL.

As discussed in part one, OIA set commensurate thresholds for CGL coverage by its construction managers during the procurement process, but made it an evaluative scoring component for the contractors to provide a narration of a proposed risk management and insurance coverage plan. The expectation was that most contractors would propose a comprehensive wrap policy in the form of a CCIP.

OIA evaluated the possibility of an owner’s controlled insurance policy (OCIP) but chose not to take on the administrative burdens. Instead it decided to push that effort and cost on the contractors, many of whom had well-established programs.

Ultimately, one of the CM@Risk contractors bound CCIP coverage in thresholds of $100 million, while another CM@Risk contractor bound straight CGL at $100 million in addition to the ancillary coverage required by the contract.

LAWA required specific CGL limits commensurate with the risks involved at each stage as its Landside Access Modernization Program (LAMP) APM, or automated people mover, is being procured on a DBFOM basis.

The developer is required to have CGL limits of $2 million per occurrence and $4 million general aggregate and $4 million as a completed operations aggregate. Additionally, the developer must also obtain railroad protective liability and property damage insurance when performing railroad-related services during construction, set at $5 million per occurrence and $10 million as a general annual aggregate.

This additional insurance policy is to be made primary to the CGL policy.

Furthermore, LAWA required its developer to obtain an excess liability policy through the entire term of the agreement of $200 million per occurrence and in the aggregate and $150 million for products/completed operations in the aggregate. The $150 million policy tail takes into account the more limited risk associated with the operations and management stage of the project.

Contrary to the expectation of many owners and even industry professionals, a CGL does not provide coverage for construction defects.

Generally, selecting insurance limits proportionate with each stage of the project minimizes the expense of unnecessary coverage while ensuring adequate coverage when the associated dangers are enhanced.

Owners may want to consider the overall amount of CGL coverage against the overall cost of a project to determine wither there is sufficient coverage. For situations where coverage appears to be inadequate, additional risk-mitigation “tools,” discussed below, should be used to offset the risk.

As there are numerous interpretations of CGL policies weaving through the courts, some even denying coverage for subcontractor error, it is further evident that while CGL policies are an important part of the insurance coverage matrix, they are not the end-all. Coverage must be supplemented by additional instruments, including surety bonds, which is discussed below.

7) Professional Liability

Professional liability insurance provides coverage for errors and omissions caused by members of the design team and other entities providing professional services, such as scheduling, estimating and building information modeling (BIM).

Owners tend not to think about professional liability insurance also for their contractors.

In this era of integrated project delivery, however, professional liability is necessary for design-build, construction management at risk, public-private partnerships and other delivery methods where the prime contracting entity has some role in the design process or provides other professional consulting. The need is axiomatic in design-build, but owners should require that the professional liability be provided by the prime entity, which often is the contractor, in addition to professional liability insurance at all tiers of service providers.

Professional liability provided by the design team in a subcontractor or even joint venture capacity, may and often does not suffice.

Construction management, especially where a robust pre-construction services program is involved, requires professional liability to cover any errors and omissions arising from design and constructibility reviews, BIM, scheduling, estimating and any other form of professional service provided. The value of construction management at risk is in fact these professional services — otherwise it is just ordinary general contracting.

At OIA, professional liability coverages were set in accordance with the specific disciplines, recognizing that coverages beyond $25 million for architecture and $5 million for engineering sub-disciplines were either impossible to attain for many firms or would severely limited the competitive playing field during procurement.

The owner, therefore, shopped the underwriters for an owner-procured umbrella policy over and above all professional services for the project, including consultants and construction managers.

The result was an owner’s protective professional indemnity (OPPI) insurance policy, providing additional coverage in bands of $20 to 25 million up to a total tower of $125 million. The benefit was a project-specific umbrella with lengthy tail coverage.

This structure used at OIA is especially beneficial given that many professional services firms simply cannot obtain or qualify for coverage in thresholds that are commensurate with mega-project risk — indeed even some of the largest architectural firms in the country carry a maximum of $25 million in professional liability insurance.

Therefore, the owner should look at supplemental coverage through other options, including consideration of OPPI.

For LAWA’s LAMP APM, the developer was required to obtain professional liability insurance of $50 million per occurrence for the lead designer and any other party involved in the design.

By anchoring its professional liability insurance requirement to the number of design professionals involved with the design, LAWA factors in the differing compositions of design teams and each design professionals’ obtain coverage. Requiring professional liability insurance in such a fashion is likely limited to large-scale projects where there is uncertainty as to a proposing entity’s structure, prior to the disclosure of insurance requirements.

However, as with any policy limit, LAWA would carry the risk of recovery beyond this professional liability insurance limit.

8) Owner Procured Insurance/Builder’s Risk

Generally, the project owner carries two critical forms of insurance coverage: Builder’s risk, which covers certain losses suffered during construction, and property casualty, which typically follows the builder’s risk, covering liability and certain losses post-completion.

Owners can transfer the builder’s risk requirement to the contractor, but larger public entities and owners should consider controlling the builder’s risk, which can often be an adjunct to existing property coverage policies.

Additional policies for owner-consideration include OCIP, which is in lieu of contractor-supplied CGL or CCIP coverage, and OPPI, which is essentially an umbrella policy over the design and construction professional’s liability policies.

Builder’s risk is project-specific insurance that protects an owner’s interest in materials, fixtures and equipment being used in the construction or renovation of a building or structure should those items sustain physical loss or damage from a covered cause.

In layperson’s terms, this coverage insures the project from damage caused by casualty events like fire, wind, lightning and other perils not expressly excluded.

Standard builder’s risk is not intended to coverage losses arising from design and construction defects, although special variants of builder’s risk are available for such coverage (e.g., LEG-2 and LEG-3).

Builder’s risk coverage also generally ends once the project achieves completion. It does not provide any form of tail or extended coverage.

Robert Alfert, partner, co-chair of construction law and litigation group, Nelson Mullins Broad and Cassel

OIA chose to procure its own builder’s risk coverage, utilizing its property insurance leverage to better its position relative to coverage scope, exclusions and cost. Given the complexity of the program, with multiple phases, components and project participants, OIA evaluated and selected the specific LEG-3 project endorsement, which provided specific and expanded coverage beyond casualty events, covering within some limitations, architectural, error and contractor defective work and ensuing damages.

Generally, LEG-3 coverage is broader and excludes only the costs of improvements to the original design, specification or materials. At project completion, OIA’s property policy takes over.

Contrarily, LAWA required the P3 concessionaire to procure a policy with a limit of $250 million per occurrence for its builder’s risk coverage, with additional Builder’s Risk coverage in the form of LEG-2.

LEG-2 provides additional coverage for resulting damage from defect, excluding the cost of remediation and remediation that would have been incurred if the property was fixed prior to the loss. This type of coverage differs from LEG-3 in that while LEG-2 excludes from coverage the “pure” costs of correcting the error, LEG-3 only excludes from coverage the costs that improve the original work or design — therefore providing broader coverage than a LEG-2 endorsement.

In managing its risks, LAWA also maintains general all-risk property insurance for $2.5 billion, which includes $250.0 million sub-limits for boiler and machinery, $25.0 million for earthquake perils, insurance coverage of $1.3 billion for general aviation liability perils and $1.0 billion for war and allied perils (terrorism).

Following the design and construction phase of the LAMP APM, LAWA requires that the developer obtain property insurance during the operations and management period of $250 million per occurrence, with specific sub-limits and insured perils to be covered by the policy.

LEG-2 and LEG-3 coverage emerged as defect exclusions and are often used in large-scale infrastructure projects around the globe, but surprisingly, they are not often seen on U.S. projects.

Given the magnitude mega-projects and all attendant risks, owners should strongly consider the additional builder’s risk coverage options available through LEG-2 and LEG-3 endorsements.

The additional costs typically weigh in favor of usage, even though these endorsements create some overlap in the overall coverage matrix provided by CGL, professional liability insurance and surety bonds.

9) Owner Controlled Insurance Programs — Commonly Known as OCIPS

An OCIP is in material respect identical to a CCIP, as discussed above.

The OCIP is a program established by the owner, where the owner procures the CGL coverage and, if a full wrap is desired, also procures the automobile coverage, workers’ comp, pollution and any other ancillary policy that the owner wishes to added to the matrix.

The advantage is that the owner controls the program, the costs and responsibility for ensuring the policies remain in effect for all appropriate timeframes; and is notified of any changes or modifications in coverage, etc.

The owner also administrates the program, though most owner’s employ a third-party firm to handle the administration. The OCIP obviates the need for the contractor and subcontractors to procure any insurance. OCIP are more effective for owner-entities that build with regularity, say a school board, as opposed to an owner that does not building with any degree of frequency.

10) Owner’s Protective Professional Indemnity

Surprisingly used only sparingly, and perhaps one of the best forms of additional coverage that an owner can obtain in addition to LEG-2 and LEG-3 endorsements, is an OPPI.

OPPI is essentially an umbrella policy that sits on top of the professional liability policies carried by the designers, consultants and contractors working on the project. It is generally project-specific, so the coverage limits are exclusively for the project itself.

Image courtesy of Nelson Mullins Broad and Cassel

Compare that to the professional liability policies provided by the contracting parties, which tend to be corporate policies covering all work, and on a declining basis, renewed annually. OPPI also offers the distinct advantage of being customized to suit the duration and post-completion risk on the project.

While coverages vary depending on underwriters, it is possible to obtain policies that insure the project through design and construction and then for a period of years following completion, up to 10 years in some instances (thus paralleling with some state statutes of limitations and periods of repose).

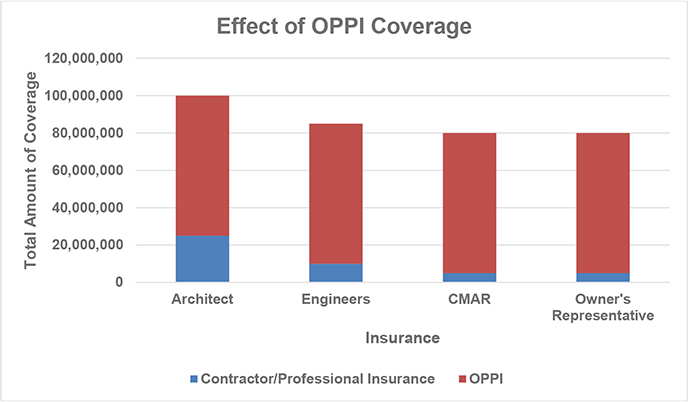

An example of how OPPI can be structured is as follows: An owner hires an architect with $25 million in professional liability coverage, engineers with coverage up to $10 million and a CM@Risk contractor with $5 million.

Given the risk on a $2 billion project, the owner decides to purchase an umbrella to provide maximum coverage up to $100 million. The OPPI is purchased in bands totaling $75 million. That provides $100 million over the architect, $85 million over the engineers and $80 million cover the CM.

Of course, the owner could structure it as well where the total coverage is $100 million for the entire team. The policies are customizable. OPPI kicks in once the underlying policy is exhausted or no longer available.

Beyond these core insurance instruments, the inherent risk of mega-projects can also be mitigated in part through the use of performance bonds and alternative security, as further discussed in Part 3. &

Part One: Initial Consideration for Owners

The U.S. has entered the era of the mega-project. Insurance must respond accordingly.

Part Two: The Core Insurance Instruments

A deeper dive into the insurance products available for construction mega-projects.

Part Three: Performance Bonds and Alternative Security

Part Three: Performance Bonds and Alternative Security

Promoting a more customized approach to risk management on mega-projects.