2018 Most Dangerous Emerging Risks

The Growing Insurance Gap Is A Serious Threat to Us All

Amid discussion of presidential Tweets and Hollywood harassment, catastrophes dominated much of the news cycles of late 2017.

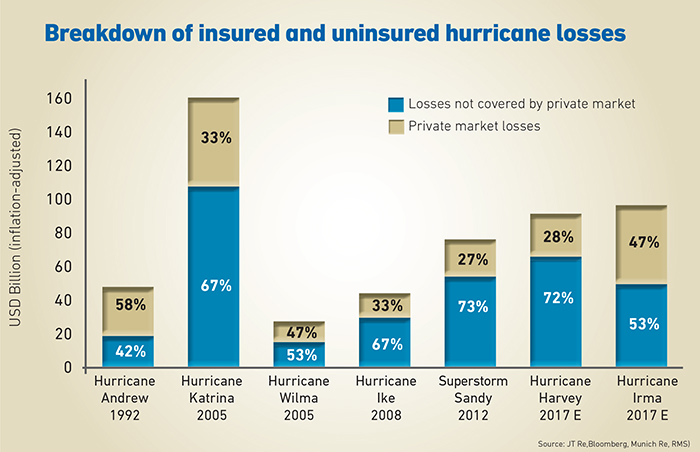

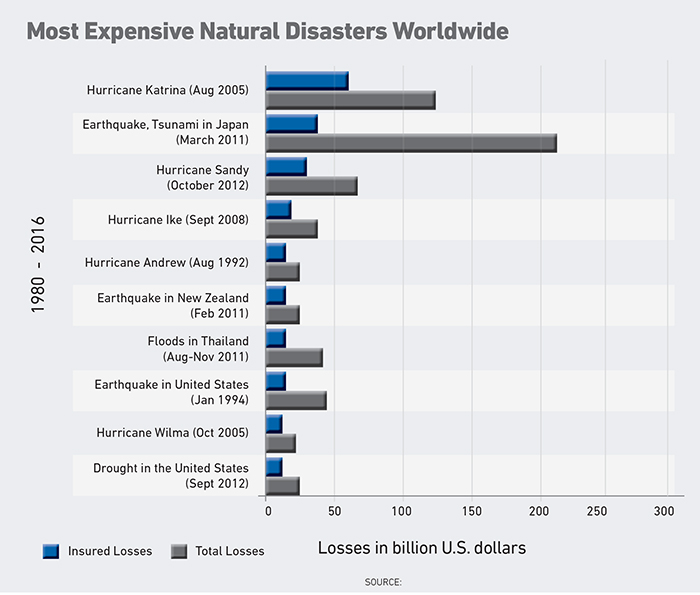

It was a record-setting year. Irma was the longest-lived Category 5 storm in the past 50 years. Harvey set a new U.S. rainfall record for a tropical cyclone. October wildfires in California were the most damaging ever endured by the state. Globally, the overall tally for natural-disaster losses amounted to $330 billion, the second-highest figure on record — 60 percent of it uninsured.

Climate change, sea level rise, increasing global temperatures … these factors and more are increasingly impacting the frequency and intensity of catastrophe-level events. Growth in population and property values are exacerbating the severity of the losses.

“These events, if anything, are getting stronger and more frequent,” said Patrick Daley, Head of Large Property for The Hartford. Even normalizing for increased property values, “any kind of bar chart you look at over the last 40 years or so, demonstrates that.”

All of which makes the protection gap — the difference between total economic and insured losses — an area of great concern, in terms of the country’s ability to rebound from disasters, both physically and economically.

“You need look no further than some of the events we saw in 2017 to see that when you have higher penetration rates for properties that are insured, the recovery is significantly faster,” said Daley.

“That’s a very big deal, and it’s something we don’t talk enough about in the industry, something we can bring to bear and should be talking more about.”

The property insurance protection gap has risen steadily over the past 40 years. In the past decade, cumulative total damage to global property as a result of natural disaster events was $1.8 trillion. At least 70 percent of those losses were not covered, according a 2015 Swiss Re study titled “Underinsurance of Property Risks: Closing the Gap.”

The property insurance protection gap has risen steadily over the past 40 years. In the past decade, cumulative total damage to global property as a result of natural disaster events was $1.8 trillion. At least 70 percent of those losses were not covered, according a 2015 Swiss Re study titled “Underinsurance of Property Risks: Closing the Gap.”

In the U.S., the problem is felt most acutely for special perils such as flood or earthquake coverage. In the event of a mega-earthquake along the San Andreas fault, experts warn that only 9 percent to 13 percent of properties carry earthquake coverage.

A dramatic example of the flood protection gap is still playing out in Texas. Less than 20 percent of homes in the Houston area were covered for flood when Harvey hit.

Nationally, there are more than 29 million properties that are at moderate to high risk of flooding, but are not subject to mandatory flood coverage because they fall outside of Special Flood Hazard Areas, according to a CoreLogic analysis. More than five million of those properties are in Florida — more than half (54 percent) of the state’s total properties. Texas and California each have three million properties at risk. Arizona is far smaller, but 68 percent of its properties are at risk, as well as 49 percent in Louisiana.

Trouble in the Gap

Some are tallying the combined losses of Harvey, Irma and Maria at up to $250 billion. Scientists are already predicting that the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season will be a repeat of 2017 — or worse.

California mega-quake losses are more speculative. For an 8.2 quake, some say a figure close to $300 billion isn’t out of the realm of possibility.

“Two or three times what happened in Harvey is a likely outcome,” said Tom Larsen, principal of industry solutions at CoreLogic. “It’s tragic, it’s big numbers, it will be very disruptive.”

Modelers have shown how an 8.2 quake could cause a length of the San Andreas fault to rip open like a 300-mile-long zipper running from the Salton Sea to Paso Robles, displacing the earth by 30 feet in a matter of seconds. All of Southern California would be hit hard at the same time.

At particular risk is the Los Angeles basin, where millions live atop a surface of mostly gravel and sand. The U.S. has never suffered a quake of that magnitude so close to a major city. The loss of life would be devastating, and the physical destruction – most of it uninsured – overwhelming.

Historically, the rate of uninsured residential losses sits consistently around 70 percent for natural disasters. The commercial gap is less acute but still problematic.

The largest commercial property owners might be adequately insured for a catastrophic loss, especially if their lenders require it. In the event of quake damage, they’d also be better able to absorb the high deductible of an earthquake policy. But many small and medium sized businesses in high-risk regions roll the dice and take their chances without the coverage they need, or carry limits too low to facilitate recovery.

The government aid needed for public infrastructure rebuilding, aid to individuals and disaster loans to businesses is increasingly high. For the next extreme high-severity event, it’s possible that supplemental appropriations by Congress could exceed the $43 billion spent in 2005 after Hurricanes Katrina, Wilma and Rita.

So if the government is footing the bill for infrastructure recovery, and insurers are paying claims for the comparative few who were adequately covered, what about the rest? Private loans might take up some of the slack. But with large portions of a region’s population displaced – in some cases permanently – incentive to rebuild or repair could be low. Businesses able to physically rebound will still suffer the loss of customers and suppliers unable to do the same.

“I think most people figure, if something that big happens, either I’ll walk away from my house and let the bank have it, or I’ll take out a loan.” — Michael Korn, managing principal and practice leader for property and marine, Integro Insurance Brokers

Rebuilding efforts, particularly for damaged infrastructure, will help offset job losses and spur growth. But the effect on residential and commercial construction will not be as robust as it might be in areas with higher insurance penetration.

The road back for an affected region is often slow, especially with high levels of uninsured losses. The rest of the country is impacted as well.

Consider the hypothetical 8.2 earthquake. California is the largest contributor (13.3 percent) to the U.S. economy, with $2.44 trillion in economic output. The state’s agriculture sector alone is a $45.3 billion dollar industry that generates at least $100 billion in related economic activity. Prolonged disruption of that economy could ripple across numerous industries. There is no precedent for a catastrophic earthquake near a major business center.

Trade pipelines would suffer. Around about 20 percent of all U.S. imports come through the Port of Los Angeles, said Martha Bane, managing director, Property Practice, Gallagher. “The supply chain would be significantly impacted … you may not be located in Southern California, but that one part of that widget you’re manufacturing may be here.”

The Ripple Effect

After Hurricane Harvey, $30 billion of securitized commercial mortgages landed on the watch list of analysts and investors worried about the risk of defaults. Of greatest concern were the properties uninsured for flood, as well as rental properties inadequately covered for business interruption or contingent business interruption losses.

That scenario would be magnified after a catastrophic earthquake, creating a destabilizing effect on financial markets.

The greatest threat to security markets “is not so much the damage but the uncertainty coming out of the damage,” said economist Barbara Stewart at a Washington, D.C. forum titled “Economic Consequences of a Catastrophic Earthquake” held by the National Research Council Committee on Earthquake Engineering.

“If there is anything financial markets cannot stand, it is uncertainty. They can deal with good news, they can deal with bad news, but uncertainty is the worst.”

That’s especially true if it causes businesses and governments to postpone financing for critical projects for an indefinite length of time.

Said Stewart, “What is the cost of the things that are not done, the projects that are not built, the activities that are not undertaken?”

In Search of Solutions

Increasing insurance penetration for perils like flood and earthquake will spread the risk and make coverage more affordable, but that’s easier said than done.

The nonprofit California Earthquake Authority (CEA) has seen an uptick of interest in the past two years, and recently surpassed one million policies. But the state’s population exceeds 37 million, most of whom live within 30 miles of an active fault, according to CEA.

Michael Korn, managing principal; practice leader for property and marine, Integro Insurance Brokers

For California homeowners, going without the coverage is simply the smarter financial move. “It’s incredibly expensive,” said Michael Korn, managing principal and practice leader for property and marine, Integro Insurance Brokers – and a California homeowner. “The deductibles are very high, and I think most people figure, if something that big happens, either I’ll walk away from my house and let the bank have it, or I’ll take out a loan.”

Unfortunately, many property owners assume that FEMA will always be there to help them rebuild. Pre-Katrina, federal spending amounted to about 26 percent of the total costs. Post-Katrina, that figure shot up to 69 percent and has remained high.

“Right now we just rely on the federal government and its grand largesse,” said Larsen. “Except that these big events are starting to [spark] bigger discussions in Congress about how much money they can continue to set aside to pay for this. So [even though] the government has always jumped in on lesser events — will it be able to jump in on the bigger events?”

The U.S. is not alone in that kind of narrow thinking, said The Hartford’s Daley. There are plenty of other countries whose citizens assume that when push comes to shove, the government will step in and save the day.

But the reality is that “over time, I think we’re going to see less and less of that — especially with some of the economic turmoil we see in other parts of the world. They may not have the wherewithal to do that.”

With the frequency and severity of disaster events increasing, the topic will need to be addressed. In 2007, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a report that concluded “Given the current approach to disaster relief funding, we project an ‘unfunded’ liability for disaster assistance over the next seventy-five years comparable to that of Social Security.”

Many believe that it is finally time to push the boundaries of mandatory coverage further. Thompson (Tom) Mackey, risk management consultant, EPIC Insurance Brokers and Consultants, said that for earthquake, a backstop program similar to the National Flood Insurance Program would be a start.

“I think that would really be the only way to adequately address the risk,” he said. “Ultimately, society pays for it either way. So do we do it upfront in a fair and controlled manner? Or do we do it after the fact, when we have to open up the government coffers, and borrow money from the global financial marketplace. It’s one of the two. Either way we have to finance the risk. Doing it proactively makes the most sense.”

“The great part about that is … it’s about the law of large numbers. If you require everyone in a certain community or certain areas to buy that insurance you avoid things like adverse selection,” added Daley.

But coverage only addresses part of the problem. Compounding the severity of uninsured risk is that those reluctant or unable to obtain policies are probably not spending money on mitigation efforts either. It’s hard to justify an investment that you may or may not ever see a return on it.

Regulations are a key factor, including more stringent building codes that address exposures. Los Angeles and other California cities have passed sweeping laws requiring owners to retrofit some of the most vulnerable commercial properties. But in the absence of laws, property owners often have little incentive to be proactive.

Proposals have emerged in recent years that tie mitigation to coverage for property owners in disaster prone areas.

“Ultimately, society pays for it either way. So do we do it upfront in a fair and controlled manner? Or do we do it after the fact, when we have to open up the government coffers, and borrow money from the global financial marketplace.” — Tom Mackey, risk management consultant, EPIC Insurance Brokers and Consultants

One idea is to offer five- to 10-year policies, attached to the property rather than the individual owner. Policies would transfer with ownership, and premiums would be lower for properties with loss-reduction features. Insurers would partner with mortgage lenders to offer low-interest loans for resilience upgrades.

There’s little down side. Banks benefit from reduced risk of loss to the property. Insurers reduce potential claim payments. Property owners benefit from added value when marketing the property to future buyers. And taxpayers take on a smaller share of the burden of disaster relief. Wins all around. But so far, that’s just a concept.

For earthquake exposure, most carriers already do offer premium discounts to policyholders — both commercial and residential — who seismically retrofit their properties.

CEA also partners with the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services to operate the Earthquake Brace and Bolt Program (EBB). EBB offers retrofit incentives of up to $3,000 to homeowners with properties built before 1979.

Continued innovation is needed. Some companies are working to address the key pain points of slow payment and coverage gaps. Swiss Re now offers QUAKE, a parametric product triggered by seismic measurement. QUAKE provides ready cash for immediate needs of public entities and corporations, particularly for expenses not covered by insurance or federal relief funds.

It’s a useful tool for planning ahead to meet a high deductible, said 2018 Power Broker® Alexandra Glickman, area vice chairman at Gallagher and managing director and leader of its Global Real Estate & Hospitality Practice. “It’s not in lieu of earthquake insurance,” she said, but it is an affordable supplement.

A company called Jumpstart is working to launch a parametric earthquake product for individuals. Such a product already exists for hurricane exposure. Assured Risk Cover’s StormPeace offers payouts based on pre-agreed conditions of strength of a hurricane and its distance to the property, even if the storm does not make landfall.

Swiss Re’s 2015 underinsurance report noted that insurers can play a vital role in strengthening the resilience of households and companies against property risks.

“Product and distribution innovation, and measures to handle accumulation exposure will be critical to help society better manage the risks,” said the report. “So too will be developing data and analytical tools to better understand the exposure.”

Investing in Mitigation

But the report emphasized that insurers cannot act alone. Public-private partnerships can help close the protection gap where insurability is limited, and governments need to provide strong regulatory environments, “set and enforce building standards, and promote mitigation to reduce risk exposures.”

“I certainly think it’s in everyone’s interest — insurance companies and society in general — that the insurance industry find ways to invest in mitigation,” said Daley. That includes working with government to set and enforce building codes, he said.

“We see time and time again … why is it that a storm with the same ferocity will have different impacts going through Florida than it does in certain places in the Caribbean? Building codes play a large role.”

Daley said that during visits to Bermuda, he notes with interest that many of th3e residences have been constructed to withstand significant wind exposure. “So when storms hit Bermuda, you won’t see the same type of impact that we saw coming out of some of the events of 2017 in places like Puerto Rico,” he said.

The industry has much more to offer than risk transfer alone. Advice on retrofits and other mitigation efforts is an area where carriers can impact the severity of claims, said Integro’s Korn.

“The insurance industry has the expertise, experience and qualifications to guide a lot of mitigation and preparation,” he said.

“The key element to finding better solutions is to not look at the problem too much just through a technical, actuarial product management lens, but really start with the consumer, whether it’s an individual policyholder, whether it’s a government,” said Edi Schmid, group chief underwriting officer for Swiss Re, while attending the reinsurer’s April 2017 event “Catastrophes — Protecting the uninsured: Solutions for a Resilient World.”

“It’s really important to understand their needs, how they think about risk, what touches them emotionally, what’s important for them, and build something around that.”

Carriers are well positioned to offer comprehensive disaster risk assessments and help risk managers create recovery plans, said Korn. That might mean meeting emergency needs like backup power and water, but also longer-term concerns like customer and supplier loss.

“You need look no further than some of the events we saw in 2017 to see that when you have higher penetration rates for properties that are insured, the recovery is significantly faster,” — Patrick Daley, Head of Large Property, The Hartford

“[Insurance carriers] have loss prevention and loss control engineers and business continuity experts — mitigation experts that should be more a part of the insurance purchasing transaction. Some insurers provide them, and many more should be.

“I think maybe there’s just too much a reliance on the idea that if we buy $1 million worth of earthquake [coverage] we’re set.

“That’s wrong. You need to be thinking about [making] whatever loss you suffer as low as it can be. Whatever’s left over, that’s when you should think about insurance.”

The Hartford’s Daley agreed. “Insurance is one part of it, but we know that’s not all of it. I think, ultimately, the insurance industry has a role to play in helping an underwriting management company, customers and society better understand these types of risks and better prepare for them.” &