Employment Practices

#TimesUp

The #MeToo and #TimesUp movements opened up Pandora’s Box, launching countless public scandals and accusations. The stories that continue to emerge paint an unflattering picture of corporate America and the culture of sexual harassment that has permeated it for decades.

“The clock has run out on sexual assault, harassment and inequality in the workplace. It’s time to do something about it,” reads the official tagline of Time’s Up, one of the most vocal groups demanding change.

The GoFundMe campaign that supports the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund raised more than $16.7 million in less than a month, making it the most successful GoFundMe initiative on record.

Funds will be used to help victims of sexual harassment and assault bring legal action against harassers, as well as provide public relations consultation to manage any media attention such suits might attract.

The problem was never really a secret.

In surveys conducted since 1980 by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 40 percent of women and 15 percent of men consistently reported being sexually harassed at work.

In a sweeping meta-analysis of 25 years’ worth of research data, published in “Personnel Psychology,” an average of 25 percent of women reported experiencing sexual harassment at work. When respondents were given clear definitions of harassing behavior, that figure shot up to 60 percent.

The current climate is just now pushing awareness to the forefront. It was reported last November that law firms in the nation’s capital are seeing a spike in inquiries about sexual harassment cases.

Laura Coppola, regional head of commercial management liability in North America, Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty

In addition, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) website is seeing visits to its harassment web page double.

There’s no question the costs to businesses can be staggering. Twenty-First Century Fox reportedly incurred $50 million in costs tied to the settlement of sexual harassment and discrimination allegations in its Fox News division, as well as a $90 million settlement of shareholder claims arising from sexual harassment scandals.

In June, the company disclosed in a regulatory filing that it had $224 million in costs during the fiscal year related to “management and employee transitions and restructuring” at business units, including the group that houses Fox News.

If time is indeed up, it won’t just impact Hollywood, Silicon Valley or Capitol Hill. It will impact every workplace, in every industry.

“It affects everybody,” said Marie-France Gelot, senior vice president and insurance & claims counsel for Lockton’s Northeast Claims Advisory Group.

“I think anybody in corporate America — at some point — has seen it or been aware of it or been around it.”

“This particular phenomenon is certainly at a much wider scope than we’ve seen in the last decade or so,” said Laura Coppola, regional head of commercial management liability in North America, Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty.

“This is going to touch many industries, many segments, and many people.”

Employers are beginning to wonder if their workplace could be next.

“I think if you’d been asking [insureds] a year ago, ‘Are you interested in hearing about sexual harassment prevention?’ I think the answer would have been, ‘No, we’re good, we’ve got it,’ ” said Bob Graham, vice president, HUB International Limited.

“But I think now everyone’s saying ‘Sure, yes, we’d like to hear something.’ ”

Leading the Conversation

As American workplaces come under increasing scrutiny, the time is ripe for a large-scale pivot in the way employers manage risks related to sexual harassment.

The co-chairs of the EEOC’s select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace expressed it aptly in 2016:

“With legal liability long ago established, with reputational harm from harassment well known, with an entire cottage industry of workplace compliance and training adopted and encouraged for 30 years, why does so much harassment persist and take place in so many of our workplaces? And, most important of all, what can be done to prevent it? After 30 years — is there something we’ve been missing?”

Experts in the management liability field unanimously told Risk & Insurance® these issues should be elevated to the board level and the C-suite.

“Just as cyber liability shifted rapidly from an IT discussion to a board level discussion, so too will the harassment and discrimination discussion go beyond HR and be elevated to the highest levels,” said Coppola. It will become a corporate-wide, enterprise-wide conversation.

“It’s going to take some time to get to that board level, but it’s going to have to happen,” said Paul King, national practice leader, management and professional services, USI Insurance Services.

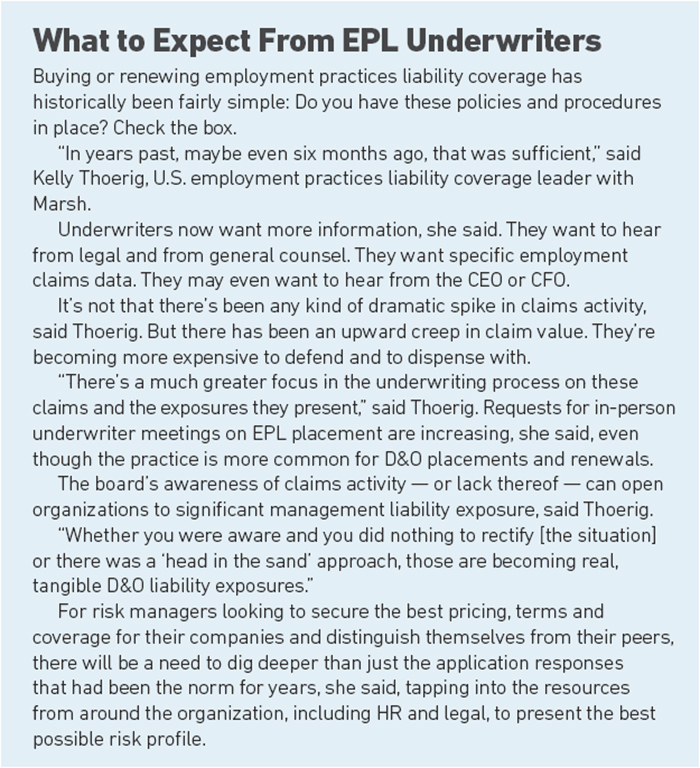

Risk managers, said Kelly Thoerig, U.S. employment practices liability coverage leader, Marsh, are well suited to lead this conversation, which means actively partnering with human resources, the legal department, the general counsel’s office and outside counsel.

“Just like the quarterback depends on the offensive line, on receivers, on the running backs, it’s not a one-man show,” said King. “This can’t be the risk manager operating in a vacuum; they have to be liaising with multiple parts of the organization.”

Added King, “Risk management and HR cannot go down parallel paths, not understanding one another. Not anymore. There’s too much at stake.”

Connecting with outside counsel can also be of great benefit to risk managers, said Coppola.

“Risk management and HR cannot go down parallel paths, not understanding one another. Not anymore. There’s too much at stake.” — Paul King, national practice leader, management and professional services, USI Insurance Services

“[They can] provide a very independent objective view of what they see in the overall market and how their knowledge of the individual client’s best practices can be improved and enhanced to ensure that they are protecting employees and the organization.”

Brokers and carriers also may be able to offer insights and services. Unfortunately, that piece is often lost because risk management and HR are siloed.

“The [knowledge of the] services that come with the insurance policy end up with the policy — in a drawer in the risk manager’s office,” said Tom Hams, employment practice liability insurance leader, Aon.

“HR doesn’t know that they exist. Even if they’re just online blogs or something like that, they could be more meaningful to the HR department than they are to risk management.

“So it’s important to make sure that companies are aware they’ve got those tools and — more importantly — to share them internally.”

Expediting Cultural Change

The X factor that underpins every aspect of these efforts is culture, experts agreed.

“It’s not so much ‘does the company have best-in-class policies and procedures in place;’ I think many of them do. I think that a significant change needed is doing a full overhaul of corporate culture, and that’s no small feat,” said Gelot.

True culture change can only come from the top level. But that isn’t likely to happen unless everyone at the top understands what the scope of the exposure could be if it’s not addressed appropriately on the front end. And for that, money talks, said Thoerig, who will be presenting on the topic at RIMS 2018 in San Antonio.

“Nothing is more instructive than real tangible claims examples and settlement amounts. Arm yourself with … recent, relevant claims examples specific to the industry and the jurisdictions the company operates in.”

In addition, said King, HR and legal should be regularly feeding claims information to risk managers to share at quarterly meetings of the board and give specific updates around these issues.

Armed with that level of intelligence, top brass can set the goals that will drive all anti-harassment efforts, said experts, putting an emphasis on identifying and correcting behavior that could potentially expose a company to liability.

Better Training and Reporting

The best anti-harassment programs are multilayered, said Hams, with each facet carefully tailored to suit the employee population, the industry and the organization’s goals. A clearly defined policy is essential, stating that harassment will not be tolerated and neither will retaliation against those who report it.

The policy should be clear that employees are expected to report harassment or unacceptable behavior. Hams said he’s seen companies go so far as to state employees who don’t speak up are in violation of the policy.

“At least it should give them pause to stop and think about what they might have seen before they click the button or sign the document,” he said.

Companies should consider how uncomfortable employees may be about speaking up. An open-door policy is a start.

But there should also be multiple reporting points throughout the organization, said Hams, and an anonymous hotline for those reluctant to bring the matter up with anyone in their chain of command, and a multilingual hotline as well.

An effective training plan will have multiple moving parts and should touch every level of the organization from the executive suite to managers and supervisors to the rank and file. Comprehensive training is especially critical for the managers and supervisors who might receive or investigate complaints.

Many large employers already have training programs that can be considered best-in-class. Small to midsized employers, however, may still be using the cookie-cutter compliance-centric training that has dominated the field for decades.

The goal of this training is to hit all the bases related to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, ticking off a list of acts or speech that would be considered illegal and affirming the company will not tolerate illegal behavior.

Overwhelmingly though, this type of training misses the mark. Studies have shown that this one-size-fits-all training is ineffective, especially when it’s a rote check-the-box exercise. Employees get the message their employer doesn’t take the subject too seriously.

Worse, it can even aggravate tensions, creating more discriminatory behavior from men who avoid working with women just to eliminate the chance of being accused of anything.

One study even found that men were more likely to place blame on the victim of sexual abuse after they’d received that type of anti-harassment training.

Even at best, compliance-centric training will still fail, because it only addresses behaviors that violate the law. But there is a broad array of behavior that — while not quite illegal — shouldn’t be tolerated.

When this kind of activity is allowed to flourish unchecked, the environment becomes increasingly toxic for those on the receiving end. It also tells employees that the company will tolerate harassment as long as it’s not overly egregious. In that case, it’s just a matter of time before the company is faced with a serious claim.

“Nothing is more instructive than real tangible claims examples and settlement amounts. Arm yourself with … recent, relevant claims examples specific to the industry and the jurisdictions the company operates in.” — Kelly Thoerig, U.S. employment practices liability coverage leader, Marsh

In its 2016 report, the EEOC’s harassment task force recommended changing tactics, exploring alternative training models such as respect-based civility training — what some call professionalism training.

The theory is “if you train them to act in a professional manner, these things tend not to happen at all,” said Hams.

The EEOC also suggested bystander intervention training, which is designed to empower employees to intervene when they witness harassing behavior.

Experts agreed whatever training programs or modules a company chooses, it’s important the training material reflect the workforce and be continuous and regularly refreshed.

A certification scheme also should be put in place to ensure the training is hitting the mark. While the law does not yet require companies to prove the effectiveness of their programs, some suggest it’s only a matter of time before the courts catch up to the problem.

What’s more, said Coppola, it’s simply the right thing to do for companies that want to confirm they’ve created a culture where all employees can expect to be treated professionally.

Zero Tolerance

Gelot and others believe a zero-tolerance policy should be a key component of an effective anti-harassment program.

“There are many companies that have Harvey Weinsteins and Matt Lauers and Kevin Spaceys working in their midst and those people are tolerated. Employees know about them — it’s not a secret.”

Particularly when the harasser is a high-level executive, companies may wrestle with the decision to look the other way or lose a key rainmaker. In a zero-tolerance environment — one that starts at the top — the decision would be clear.

“What we saw with Matt Lauer and Charlie Rose — they were terminated immediately as the accusations came out. That’s zero tolerance. That’s sending a message to all of the employees within the company that this is completely unacceptable, we won’t tolerate it, and [it] clearly sends a message to the public at large.”

Employers should promote a workplace culture where all forms of harassment and discrimination are unacceptable and reportable, said Gelot. That’s the only way to take the fear and the stigma out of reporting.

That said, the EEOC offers a word of caution on zero-tolerance policies applied militantly without regard for common sense. Employers should hash out the specifics of which acts merit immediate termination versus a warning.

Overzealous application of the zero-tolerance doctrine can backfire if an employee fears her coworker’s children will go hungry if she reports his lewd or sexist jokes.

Creating a Dialogue

As with managing any other exposure that touches everyone, robust sharing of ideas and best practices has the power to improve the risk profile of entire industry sectors.

Facebook raised eyebrows in December, making public its sexual harassment policy in full.

“I hope in sharing it we will start a discussion, both to help smaller companies thinking about this for the first time, and to improve our own practices by learning from other companies,” wrote Lori Goler, Facebook’s global VP of people, about the company’s bold move.

That level of disclosure is making some risk professionals uncomfortable. But others acknowledge the wisdom of it.

“Any time you can share best practices that’s probably a great idea, because no one has all the answers … or at least not all the right answers,” said Graham.

“There’s a reason they did that, and I think it’s for all the right, positive reasons. They want to drive the momentum that is going to reduce or even eliminate what we have seen in corporate America over the last 50-plus years. They want to lead by example, they want to be the model and rightly so,” added Coppola.

“I think we are at a perfect time in our economic environment that allows the evolution of equality in our workplace.”

Part of that should involve making the workplace more egalitarian, said Gelot, and figuring out “how to make female employees not feel ostracized by a ‘boys’ club’ atmosphere, and actively championing the ascension of women into senior rolls.”

“We can’t focus on the past,” said Coppola. “But we can work very hard collectively as a community, and within the insurance industry specifically, to move forward.” &