Black Swans

The Darkness of the Sun

“Daddy, wake up! Come see the rainbows!” 6-year-old Amanda LeBlanc insisted as she shook her father out of his slumber. Joel LeBlanc stirred slowly, feeling like he hadn’t slept at all.

“What? Go back to bed,” he grumbled, rolling over.

“No, Daddy you have to look,” insisted Amanda, throwing the bedroom curtains wide open. Joel squinted at the light, confused. It was way too early for sunrise, wasn’t it?

Joel hoisted himself out of bed and joined his daughter at the window, catching his breath at the sight. “Huh. You know what that is, honey? It’s called an aurora. Don’t see that every day — not in Florida anyway.”

“I’m going outside to take a picture,” Amanda declared, cantering off.

Northward, there was less wonderment and more worry. Scientists had warned that week of a large coronal mass ejection (CME) that the sun had hurled toward Earth. Only three days later, it was followed by a pair of still-larger CMEs. The latter two bursts combined during their brief journey from the sun, pushing billions of tons of highly charged particles toward Earth at unprecedented speed, thanks to the path cleared by the earlier blast.

Scientists’ predictions on the size and speed of the event fell short of the mark. But even if they’d been right about everything else, they couldn’t have gauged that the CME’s magnetic field was aligned in a way that left Earth at its most vulnerable, allowing the maximum infusion of charged plasma into the Earth’s magnetosphere. It was a recipe for a perfect solar superstorm.

By the time the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center issued an urgent warning, there were only minutes left to act. Power generation companies kicked into emergency mode, working to mitigate the impact by taking transformers offline.

But even large generators couldn’t act fast enough. Geomagnetically induced currents flowed into the power grid in a matter of minutes, overheating extra-high-voltage (EHV) transformers and frying coils, destroying or damaging hundreds.

The North Atlantic corridor was hardest hit, thanks to higher ground conductivity along the coastline. In short order, upwards of 35 million people from New York City to Washington, D.C. were suddenly without power. There was an eerie stillness that morning as schools and many businesses were forced to remain shuttered.

Backup-generator owners went in search of fuel, but most gas pumps had stopped functioning immediately or soon afterward.

ATMs were all down. Within hours, land and cell phones would fail, and water could no longer pump. Worse, wastewater treatment plants shut down, causing sewage to overflow into drinking water.

Beyond the area affected by the power outage, disruptions to global positioning systems and satellite communications wreaked havoc with cellular networks, financial transaction processing and logistics operations.

The hardy Northeasterners made the best of it at first, boiling water on camp stoves, firing up barbecues and grilling the thawing food from their freezers. But before the week was out, nerves had frayed. Residents and businesses demanded answers from utilities and government officials.

The news was bad — very bad. It’s not as if hundreds of EHV transformers were warehoused waiting to be called into service. Replacements had to be ordered. and replacement for any given transformer would be at least five months and possibly up to a year or even longer, given the high level of need and the short list of manufacturers.

Units coming from foreign manufacturers would take even longer, involving arduous and complex transportation arrangements.

Residents and business owners were stunned. Public officials explained that with no power or fuel, no water pumps or waste treatment facilities, no readily accessible food supply and badly strained emergency services, there was no option other than to evacuate the affected regions.

The impact to the economy was staggering. National companies struggled to maintain communications with evacuating employees, while putting plans in place to shift operations to other locations. But an overwhelming number of small and mid-sized local businesses without the means to relocate simply folded.

Companies with business interruption or contingent business interruption policies presumably triggered by the mandatory evacuation breathed a sigh of relief, not yet aware of the lengthy battles they’d face later on about whether or not fried transformers, or the incapacity of the power grid itself, constituted a property damage trigger under policy terms.

Supply chains nationally and globally faced upheaval as companies raced to secure secondary suppliers. Those select few companies that had chosen to take up supply chain coverage quietly congratulated themselves and used the opportunity to its fullest advantage while their competitors faltered.

Once the dust had settled, much of the North-Atlantic corridor was a patchwork of ghost towns. Members of the Army and National Guard were stationed in the region to curtail damage from looters and gangs who evaded evacution, sometimes squatting in unoccupied buildings and setting fires at night for light and warmth. Many buildings that hosted squatters would eventually need to be condemned.

Two years later, a handful of transformers still awaited replacement. Only a fraction of the evacuated population had returned, and local governments struggled to rebuild long-vacant communities. Estimates calculated the total economic cost at upwards of $2 trillion.

The Inevitable Storm

The largest solar storm in recorded history occurred in 1859. It was dubbed the Carrington Event, after British astronomer Richard Carrington, who witnessed the megaflare. He was the first to realize the link between activity on the sun and geomagnetic disturbances on Earth.

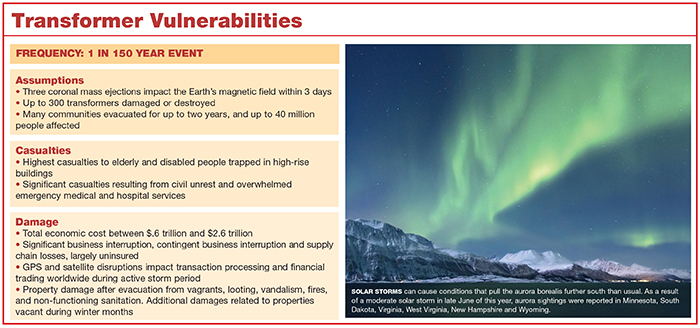

During the event, Northern Lights were reported as far south as Cuba and Honolulu. The flares were so powerful that people in the Northeastern United States could read their newspapers just from the light of the aurora. U.S. telegraph operators reported sparks leaping from their equipment — in many cases setting fire to nearby materials.

Now, take a storm of that magnitude and let it play out in the modern world. Far smaller events have occurred many times. One such storm struck in 1989, taking out Quebec’s power grid in less than two minutes, causing $6 billion in damages and leaving millions of people without power for nine hours.

For the sake of comparison, scientists measure these storms using an index based on nano-Teslas (nT). The lower the number, the harder the Earth’s magnetic field shakes when a storm hits. The Quebec storm in 1989 measured at -589 nT. The far more powerful Carrington Event is estimated at around -850 nT.

And then there was a near miss in July 2012. Had that solar blast occurred only one week sooner, the Earth would have been directly in its path, and scientists calculated the storm would have clocked in at up to -1,200 nT. The fabric of society would have been profoundly altered, and we would still be picking up the pieces today.

“The concern becomes, now that we know, do we make the choice to act?” — Kyle Beatty, president, Verisk Climate

There is more or less universal agreement among experts and scientists that another Carrington-level event or stronger is an inevitability — the only uncertainty is when. Some experts even opine that this kind of event shouldn’t even be called a Black Swan, because the probability is higher than most might realize.

In an article published in the journal “Space Weather” in 2012, solar scientist Pete Riley of Predictive Science Inc. calculated that the probability of a solar storm at the power of the Carrington Event or stronger in the next 10 years is around 12 percent.

The potential impact of such an event to our hyper-connected, electricity- and satellite-dependent society is a sobering prospect, and one that is netting an increasing amount of interest.

In 2013, Lloyd’s published the report that our scenario is partially based on, “Solar Storm Risk to the North American Power Grid,” in partnership with Atmospheric and Environmental Research Inc. (AER), a division of Verisk Climate.

“This is a topic that is drawing strong interest in the government levels at a national and international scale, because the impacts could be so large and because this is one of the only natural perils that could create simultaneous impact across continents,” said Kyle Beatty, Verisk Climate president, who worked on the study. “… When we get into an event of this size, it would impact Europe as well — it’s a global phenomenon.”

“We understood that the engineering and science communities were talking about space weather as a potentially high impact phenomenon,” added Nick Beecroft, emerging risks and research manager at Lloyd’s of London.

“But we felt that the understanding of the phenomenon and the potential impact on the insurance industry was very limited.”

Doomsday Assumptions

Experts stress that while it’s popular to paint this level of solar superstorm as a virtual “doomsday” event, that outcome need not be the case. The key is to commit to doing something about it now.

Since the 1989 Quebec storm, the Canadian government has invested $1.2 billion into protecting the Hydro-Quebec grid infrastructure. But you have to wonder how many billions could have been saved if that investment had come sooner.

“If we were to experience a major solar storm event — and I really should say it’s a question of when, not if — there could be extreme ramifications for power grids and for all those technologies that rely on satellite navigation systems,” said Beecroft.

It would require worldwide cooperation and investment to build in resilience to key systems, he said, as well as enhanced satellite systems and technology to improve monitoring and early warning systems for space weather events. In addition, it’s likely there would be “much greater demand for specific insurance products that would be able to respond to an event like this.”

At the risk manager level, Beecroft said, organizations around the world should be thinking “about how they can diversify their reliance on power systems and on key technologies.”

But Beecroft and other experts drive home that there is simply no reason for all of these things to happen after the fact.

“The concern becomes, now that we know, do we make the choice to act?” Beatty asked.

Something else that needs to happen sooner rather than later is the development of strong plans and procedures, especially on the part of power generation companies, said Lou Gritzo, vice president of research at FM Global.

Gritzo said the nonprofit North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC) has already developed recommendations to help power generators respond in such an event.

“The big wildcard is, when push comes to shove and power generators have to make those difficult decisions about what they’re going to do, do they do the right things? And how many of them do the right things?” he said.

The ideal scenario, said Gritzo, is that when the storm hits, the power generators most likely to be affected by the storm disconnect their power supply from the grid and adequate power can be temporarily supplied to the grid by other generators in areas where the storm is not going to be as intense.

The ability to make that happen quickly, said Gritzo, could go a long way toward shifting from a doomsday scenario to one of minimal consequences.

He also said risk managers should be asking power suppliers some hard questions to help them assess the need for additional investments, such as a backup power system.

Not taking any action would be a mistake. “If there’s one number in this whole report that’s significant,” said Beatty, “it’s the estimate that the return period of a Carrington-like event is estimated at around 150 years,” a figure that can be backed up with evidence tracing back to 17 B.C.

Bottom line, he said, is that “the likelihood is high enough that we actually have a responsibility to act.”

Additional 2015 Black Swan coverage:

Welcome to the ARkStorm

Welcome to the ARkStorm

A 45-day superstorm floods California and dishes out economic catastrophe.

To Clean Up a Dirty Fight

To Clean Up a Dirty Fight

A dirty bomb detonated in Manhattan could make a ghost town of the most populous city in the U.S.