Supply Chain

Metals That Threaten Reputations

Of the 6,500 companies that file with the Securities and Exchange Commission, about 4,000 are impacted by the Dodd-Frank Act’s Section 1502, which requires reporting any “conflict minerals” used in their products.

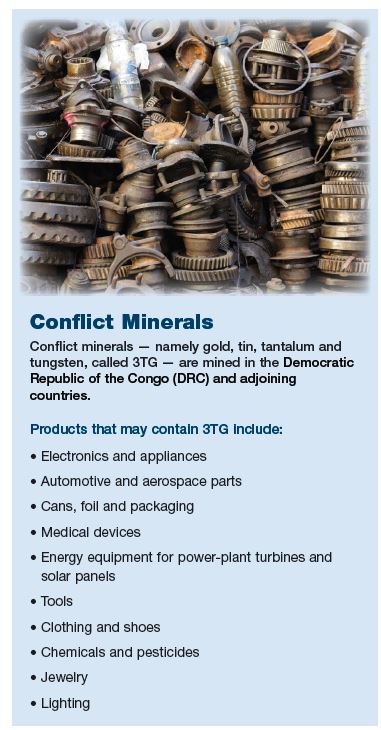

Conflict minerals are those mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and adjoining countries: Angola, Burundi Central African Republic, Congo Republic (a different nation than DRC), Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

The new SEC disclosure requirements demand immediate review of many companies’ supply chain management policies and procedures. It calls for disclosure of source-of-origin and requires due diligence to determine the presence or use of very common materials inherent in conflict minerals, namely gold, tin, tantalum and tungsten, called 3TG.

Non-compliance could result in criminal or civil penalties. At the very least, those failing to comply run the reputational risk of having their names associated with the use of conflict minerals.

“This is a name and shame law,” said Rich Goode, senior manager, Climate Change and Sustainability Services at Ernst & Young.

“I can envision someone from the SEC making public a list of companies that say they source from the DRC and are not conflict-free,” he said.

Organizations making brand-name consumer electronics don’t want “Greenpeace, Enough.org or Amnesty International saying your product contributes to enslaving children in Africa. That’s a reputational risk for sure,” he said.

Adding to the risk is the fact that the SEC’s disclosure requirements are easily misunderstood — and some companies may not even know they use these minerals.

Companies also may overthink the SEC requirements, causing more work and expense than necessary, and still may not be in compliance with the law. The SEC estimated that initial compliance costs for the affected companies will run about $6 billion.

Identification and Disclosure

To comply, organizations must first determine whether the requirements are applicable to their business. If so, they will need to conduct a “reasonable country of origin inquiry” to identify and disclose the minerals present in their supply chain.Ultimately, they must file a Conflict Minerals Report (CMR). The report also may be submitted to a certified independent third party audit, according to the SEC.

Sounds simple enough, right?

Hardly. Goode said companies are scrambling to determine if their products contain conflict minerals and to identify the sources of those minerals. “It can come down to the individual smelter.”

Companies need to make reasonable efforts to identify the sources of the 3TG in their products. They cannot, for example, skip looking for gold.

“However, if in their efforts to identify all the 3TG in their product, a company misses one component, this is not a deal breaker,” he said. “In fact, an essential part of the rule is for companies to show continuous improvement year over year.”

The other point, Goode said, is that the law is “nuanced.” While the SEC allows a company’s approach to be “reasonable,” meaning there are no penalties if a product or supplier is missed, “there are a lot of subtle nuances in areas — like risk mitigation, the need for a grievance mechanism or having a conflict minerals policy written and posted on the company website — that many companies can miss.”

In short, companies should understand what they need to do to be compliant, but they also should know that they are not required to determine with 100 percent certainty (especially in Year 1) the source of all conflict minerals in their products.

“The SEC gives companies some time and leeway to improve year over year, but it’s not a two-year free pass. It’s progress, not perfection,” Goode said.

“There is no rule that says you cannot use these minerals in your products — because they are almost essential to many products. There is also no law against sourcing from the DRC,” Goode explained.

In fact, “we tell our clients not to put an embargo on DRC — they should source from DRC, because they need the trade and the business.” However, companies should focus on conflict-free sources within the DRC, he noted.

What is Section 1502?

The Dodd-Frank Act, passed by Congress in July 2010, directs the SEC to issue rules requiring certain companies to disclose their use of conflict minerals — certain minerals from mining operations in the DRC — if those minerals are “necessary to the functionality or production of a product” manufactured by those companies.

Congress enacted Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which amends the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, because of concerns that the exploitation and trade of conflict minerals by armed groups is helping finance serious human rights abuses in the DRC region.

The final rule, issued on Aug. 22, 2012, applies to companies that use 3TG minerals if:

* The company files reports with the SEC under the Exchange Act; and

* The minerals are “necessary to the functionality or production” of a product manufactured or contracted to be manufactured by the company.

Issuers must comply with the final rule for the calendar year beginning Jan. 1, 2013, with the first reports due May 31, 2014, according to the SEC.

The Complexity of Compliance

There are a number of ways of dealing with the disclosure requirements, including by using software to keep track of supply chains and findings, or by working with an outside organization to investigate the use of conflict minerals by the company and its supply chain.

Because of the complexity of compliance, Goode said, companies that use these minerals may want to seek outside guidance.

“Some companies are going to overthink it and some will under-think it,” he said. “You want a pragmatic, repeatable program in place, because this isn’t a one-time thing. This law doesn’t look like it’s going away anytime soon.”

At the same time, the initial effort may require the most focus. A company putting a compliance program in place in Year 1, “won’t have to do the same thing in Year 2,” Goode said.

He cautioned, however, that taking “20 internal employees off their jobs to cover this  issue” may not be the most cost effective way to address compliance, because those employees will be taken away from performing their core jobs.

issue” may not be the most cost effective way to address compliance, because those employees will be taken away from performing their core jobs.

Organizations that opt to retain an outside expert should “look for someone who can help make up a program that fits within the confines of the existing infrastructure and doesn’t uproot the whole company,” Goode advised, adding that the goal is to make sure that “next year, the program is part of the way the company normally does business.”

Chris Caldwell, chief executive officer of LockPath, a risk management and compliance software company, agreed. Because companies will have to document their due diligence, this will become an ongoing “living, breathing thing,” within an organization, he said.

Caldwell said his company’s services are “not part of the decision of how companies remediate; we help by providing the initial standard questionnaires so they can perform the ‘reasonable country of origin’ inquiry and ask questions of their suppliers about where minerals are being sourced.”

If companies do discover these minerals in their supply chains, there are provisions within the reporting for them to declare that. The software provides questions to ask suppliers and establishes a protocol, he said.

Caldwell’s advice? Get started. “This is a whole new risk that needs to be analyzed and determined how it fits into the overall risk picture.”

He noted that there “are a lot of fine service providers out there that are experts within conflict minerals.”

Penalties of Noncompliance

While there are financial and reputational risks, “the SEC is not interested in putting a bunch of people in jail next year,” Goode said. What they are interested in is identifying companies that are “willfully misrepresenting their position” with the use of conflict minerals. At some point along the way, said Goode, these intractable companies are likely to find themselves facing “heavy fines and jail time on their hands.”

But even for companies that are not deliberately flouting the law, just appearing to be noncompliant could seriously impact a company’s reputation, said Chris Silva, an industry analyst at the San Mateo, Calif.-based Altimeter Group, an independent research firm focused on helping industries understand and develop strategies for market disruptions.

“I have seen it impacting the brand and marketing,” said Silva, “and how everybody from Apple to Samsung and anybody else making something with semiconductors in it is approaching the issue.”

Silva pointed out the instant repercussions when Apple decided to back out of the Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool’s (EPEAT) green electronics certification program.

“Apple simply backed out because EPEAT was placing restrictions on their supply chain,” said Silva. “It was placing conditions on their ability to audit things like the origins and disposal of components. As soon as they [Apple] did that, there was backlash. The backlash from the press and users was huge.”

Apple soon changed its position, amid reports that some government agencies and schools that use the EPEAT certification system might drop Apple products, such as iPads and Macintosh computers.

While the issue of conflict minerals may “still be a little abstract for the buyers of cellphones, the manufacturers are very aware of this issue,” Silva said.

“At the end of the day, until someone designs a better mousetrap in terms of semiconductors and things that power smartphones, they will require trace elements like tantalum — and those things are not widely available,” Silva said.

In fact, he added, some estimate that “all of the tantalum in the world would fit inside of a 200-square-foot room. So it’s extremely scarce and also critical to the devices that we use and rely on every day.”