Risk Insider: Joe Cellura

Keep Head Trauma in Mind

This is part one of a two-part Risk Insider post by Allied World’s president of North America Casualty Joe Cellura on the dangers of scholastic athletic head injuries.

He runs the plays from yesterday’s practice in his head.

Flashing back to last week’s game, he remembers the sharp crack of the helmets as he and the other team’s wide receiver collided. He vaguely remembers everything going black as teammates and coaches gathered around him in a circle of concern.

He needs to push aside fear and get pumped up. What are the chances he gets hit again anyway?

Pretty high, actually.

Concussions among high school and middle school athletes are becoming increasingly common. While high school football accounts for 47 percent of all reported sports concussions, it is estimated that one in five high school athletes will sustain a sports concussion during any given season.

The rising prevalence of concussions in sports at the high school and middle school levels pose a difficult dilemma for risk managers and insurers.

Today, the risks of injury from high impact sports at these levels have serious implications for the risk management landscape and for municipalities more broadly.

While football is a key driver of concussion related injuries at the high school level, and the focus of much attention at a college and professional level, ice hockey and soccer pose significant head health risks as well.

Across all sports, four to five million concussions occur annually, with the numbers rising among middle school athletes. When signing their children up for team sports, most parents do not expect that their child will sustain injuries to this level of severity at such a young age.

In fact, many would think that concussions are more likely to occur in a professional setting, where the stakes of winning or losing are higher, and players are more willing to take risks.

But here are the stark facts. Concussion rates among students age 8-19 have more than doubled in sports such as basketball, soccer and football between 1997 and 2007, even though participation in these sports overall has declined.

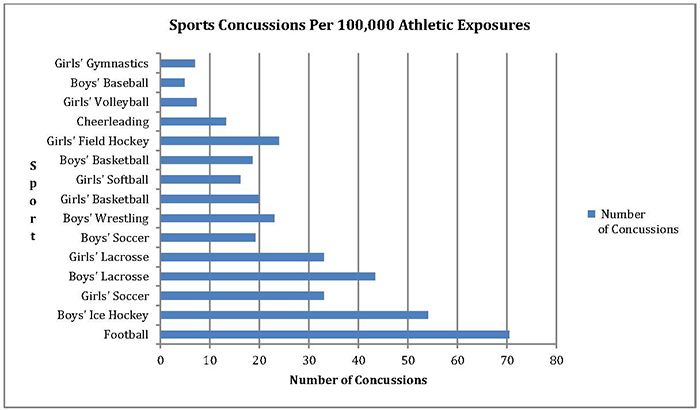

Research shows the number of concussions across all high school sports to demonstrate the amount of risk associated with each sport. The chart below indicates the average amount of sports concussions taking place per 100,000 athletic exposures.

An athletic exposure is defined as one athlete participating in one organized high school athletic practice or competition, regardless of the amount of time played.

While the numbers vary, the trend is alarming as concussions occurring in both male and female athletes continue to grow. Fully 33 percent of high school athletes who have a sports concussion report two or more in the same year.

High school athletes who have been concussed are three times more likely to suffer another concussion in the same season. While the first hit can prove problematic, the second or third head impact can cause permanent long-term brain damage.

Ninety percent of most diagnosed concussions do not involve a loss of consciousness, so it’s not always glaringly obvious when a student should step off the field. Perhaps even more troubling, 15.8 percent of football players who sustain a concussion severe enough to cause loss of consciousness still return to play the same day.

Fifty percent of “second impact syndrome” incidents – brain injury caused from a premature return to activity after suffering initial injury (concussion) – result in death.

Cumulative sports concussions are shown to increase the likelihood of catastrophic head injury leading to permanent neurologic disability by 39 percent. The most prominent place where the effects of this kind of head trauma are evident is in the NFL.

NFL athletes have historically experienced concussions and head traumas as part of the sport, and for many years, the full extent of neurological damage was not appropriately discussed or acknowledged.

Rumors of retired players becoming disabled and whispers of players dying young from head injuries began to build, until a bright light was cast on the reality of the situation in a court of law.

In April the organization was ruled to be responsible for baseline medical exams for retired NFL players, monetary awards for diagnoses of ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Dementia and certain cases of CTE, as well as education programs and initiatives related to football safety.

This settlement is costing the NFL an enormous amount of money, with some estimating the cost at $1 billion over 65 years. The NFL itself expects that 6,000 of the nearly 20,000 retired players will someday suffer from debilitating diseases caused by traumatic brain injuries.

It stands to reason that other organizations in the world of sports could face similar financial consequences. In my post next week I’ll discuss how broad the risk could spread and what carriers and risk managers should be thinking about.