LNG Growth

Frozen Gas, Hot Market

In September 2008 the insurance industry couldn’t stop talking about the federal bailout of AIG. At the same time, another major event — Hurricane Ike — was unfolding in the Houston region.

The storm blew through an area that extended from Texas and into the Louisiana Gulf Coast, including a small nook of lowland that was home to an under-construction liquid natural gas (LNG) terminal. Ike’s storm surge overwhelmed the facility’s defenses.

When Risk & Insurance® arrived to report on the story a week later, the water had receded. Those in control were scrambling to find workers in the (previously evacuated and flooded) region, and those workers they did contact were busy cleaning debris and stinking mud, and chasing away snakes and alligators.

The job for the insurance adjuster and the facility’s risk professionals and engineers was how to get the site construction back underway. Construction interruption can be as onerous a loss as business interruption, particularly for multibillion-dollar industrial facilities.

Why, then, would any company build such a plant in America’s hurricane alley?

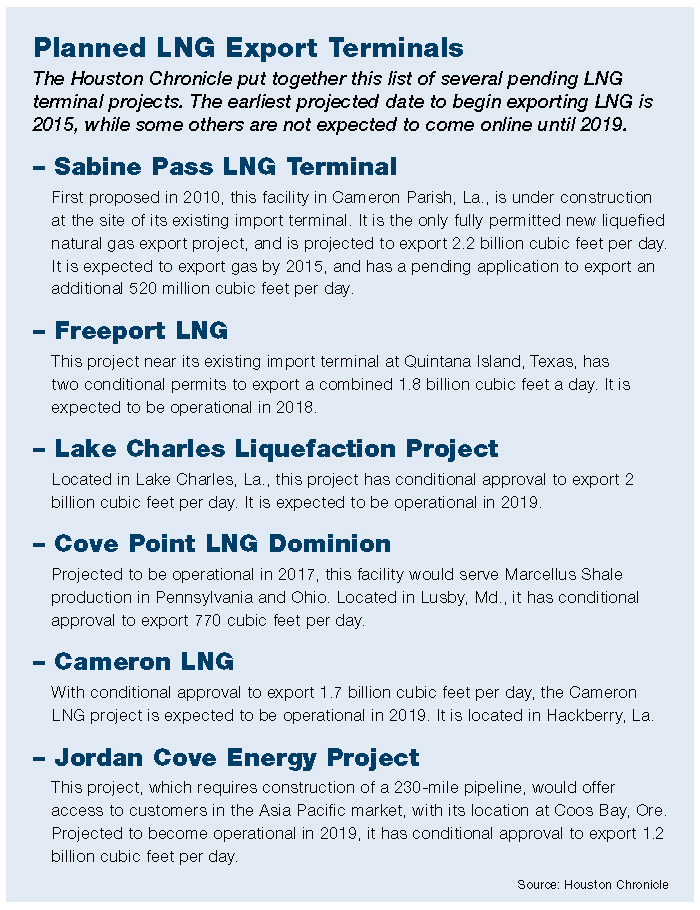

Fast-forward six years, and multiple billion-dollar LNG terminals are in the works, along the Gulf Coast and around the country. But whereas LNG plants historically have been built to import natural gas, today’s terminals are being designed to export the fossil fuel. Thirty-one LNG terminal projects, to be exact, have applied to the U.S. Department of Energy to export.

They are part of America’s energy revolution — albeit a niche part. The boom in domestic gas production begins upstream from the coast terminals and storage facilities, from the midstream transportation and processing facilities, to the wells where the raw materials are extracted, often through hydraulic fracturing (aka fracking) wells.

“The opportunities are endless and phenomenal from what I see for the next 25 years,” — Tony Carroll, executive vice president for marine, energy and construction, Aspen Insurance

The United States is exploding with domestic energy, not literally but figuratively, especially with natural gas. So much so that, with natural gas prices driven so low in the States, energy firms are looking to ship gas abroad — particularly to Asia.

The LNG facilities themselves are awe-inspiring to the layperson, with their gigantic storage tanks and their massive exposures. In early July, the state of Alaska and four energy firms entered into a joint-venture agreement for a $45 billion to $65 billion project on the North Slope. The project involves an 800-mile pipeline and an LNG export plant, due to “feed Asia’s rising demand for LNG” by the mid-2020s, according to a Reuters article.

Sabine Pass LNG Terminal, a former import-only terminal owned by Cheniere Energy Partners near the Texas-Louisiana border, is under construction to add a processing plant on-site, valued initially at $6 billion. The plant is credited with kicking off the LNG export craze and is the first plant of its kind to gain licensing approval for both export and import (with first exports expected to occur in 2015).

LNG is a proven technology with plenty of history — the first LNG plant was built in 1912, the first marine terminal in 1971.

How will this play out? According to the “Annual Energy Outlook 2014” from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, net exports of LNG will increase by 3.5 trillion cubic feet from 2012 to 2040, which will account for 48 percent of the total increase in U.S. natural gas net exports in the timeframe.

Beside energy companies and their investors, other stakeholders set to benefit from the domestic natural gas bonanza are energy underwriters.

On the phone, Aspen Insurance executive Tony Carroll’s optimism at the possible size of the market was palpable. The range of premiums to be collected is vast — from the marine risk involved in delivering equipment and supplies to construct and operate facilities; to upstream wells; to the construction risk on the dozens of processing plants being built midstream; to the petrochemical facilities turning the gas into plastics; to the buildup of LNG export terminals on the coast — involving all lines, from property to casualty, from environmental to business interruption and everything in between.

“The opportunities are endless and phenomenal from what I see for the next 25 years,” said Carroll, Aspen’s executive vice president for marine, energy and construction.

Capacity is ready, plenty of it, Carroll reported. Exposures are massive enough to offset the price drops you’d expect when supply increases.

Yes, said brokers we spoke with, energy underwriters are getting the word out that they can and will write any and all lines of business for the energy boom.

Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance is one market seeking opportunities in the property construction line.

“We are targeting. We do like it. We are excited about that market growing,” said Rob Tricamo, vice president, construction for BHSI.

Energi is another new player — a Peabody, Mass.-based provider of specialized insurance and risk management solutions for the energy business — willing to write up to $200 million in limits — though not yet LNG.

“We’re writing just about everything but,” says Jim Bowles, chief underwriting officer.

That could soon change. One Energi insured, added Justin Russo, senior vice president and head of claims and loss prevention, is in the process of developing a multi-fuel facility, with LNG as the final phase.

Risk Onshore, Risk Offshore

Of course, when energy companies submit a risk, underwriters may not be unconditionally eager to write each one. Upstream, where raw materials are extracted, underwriters appear to be facing a groundswell from landowners claiming some sort of damage (from water pollution, ground movement, earthquake).

A heat exchanger and transfer pipes at Dominion Energy’s Cove Point LNG Terminal in Lusby, Md. Federal regulators concluded that Dominion Energy’s proposal to export liquefied natural gas from its Cove Point terminal on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland would pose “no significant impact” on the environment.

“To date, very few cases have settled with these types of allegations, but the volume of claims is unprecedented and there are few laws in place to mitigate this trend,” said M. Adam Hall, senior vice president at Alliant Energy and Marine.

For LNG, Hall’s point of view is that the largest exposure is in the processing, given the complex industrial plants, the highly flammable liquid gas, and the high and low temperatures involved.

Such appears to be the case for LNG processing, or fractionation, facilities being built on-site at import/export terminals along coasts.

“For the export facilities being constructed at existing import locations, the fractionation facilities being constructed represent a higher degree of fire and explosion potential,” wrote Tim Kania in an email.

Kania is senior vice president of construction and energy for Liberty International Underwriters, which insures LNG facilities around the world.

Coast-bound LNG terminals also face natural catastrophes — perils with names like Ike and their fierce winds and high seas — and that surely represents an exposure.

Even the optimistic Carroll foresees the possibility of a bottleneck in “nat-cat” coverage in the Gulf. Everyone is buying separate limits for differing perils, so accumulation could become an issue.

David Mittelholzer, managing director with Aon Risk Solutions’ energy practice, does not see an accumulation problem yet for underwriters, with the exception of natural catastrophe capacity for windstorm and flood.

He is familiar with several of the LNG projects on the Gulf coast at varying stages of permitting, development and planning: Each with its own operators, financial arrangements, risk appetites and insurance requirements — often dictated by lenders.

As concentrations of energy-related projects and investments increase in the area with additional oil, gas and petrochemical projects being commissioned — each requiring fairly significant limits for flood and named windstorm — they may strain catastrophe capacity, he said. After all, as soft as the property market is, there is still a finite amount of catastrophe coverage.

For example, on the construction of a $2 billion plant, Mittelholzer usually sees “full-value coverage” — or $2 billion in insurance, fully syndicated across a coterie of carriers. For CAT coverage, on the other hand, only $200 million to $300 million in limits may be available at reasonable prices.

Streaming Risk Management

Yet, added Aspen’s Carroll, these LNG terminals are not being built willy-nilly.

“They are building these things with significant protection for potential windstorm and flood,” he said, including massive storm walls. Older import facilities — perhaps like the one hit by Ike — are being upgraded.

Out of the 33 LNG plants that Carroll counts out there, seven to eight have come through Aspen as submissions for underwriting.

“If you’re putting $18 billion into a facility, there are going to a be a lot of controls,” agreed Jason Pugi, vice president of general casualty at Allied World Assurance Co. — not the least of these being the regulatory oversight for such complex, industrial operations.

Risk professionals for these energy operators are also no strangers to contractual risk management. They mitigate risk by signing long-term (20- to 25-year) purchasing agreements with clients, for instance, Mittelholzer said.

“They’re required to effectively pay regardless of market conditions,” he said of buyers.

Up and down the natural gas stream, operators and service firms enter into master service and processing agreements, outlining operational risk, expectations and responsibilities, said Hall. Operators are hiring full-time counsel and contract advisers to tap their expertise on a regular basis.

Still, losses will happen — one issue brought up by several experts we interviewed. It’s simple math. The more natural gas operational activity, the more construction of processing, storage and import/export terminals, the greater the exposure.