Liability

Nursing Home Downfalls: What Happens When Evacuations Are Delayed

A nightmarish scene unfolded in Port Arthur, Texas, after Hurricane Harvey. Law enforcement and volunteer teams forcibly evacuated a flooded nursing home that waited too long past the window of opportunity to launch a safe evacuation.

Not even two weeks later, amid the chaos of Hurricane Irma, another crisis was brewing at a nursing home in Hollywood Hills, Fla. This time though, help didn’t arrive in time. Eight vulnerable residents died after a few days in the sweltering facility with no power. Six more died of related complications in the weeks that followed.

The latter facility has since been shut down, and the operators of both facilities are facing serious scrutiny from law enforcement as well as regulatory agencies. It’s no surprise multiple lawsuits are already in process.

Yet neither of these incidents is entirely isolated. There are long-term care facilities across the country that, in the event of a disaster, could be one questionable decision or one poorly executed procedure away from finding themselves publicly pilloried.

Crisis management in skilled nursing facilities and long-term care facilities is an incredibly complex endeavor that takes the cooperation of risk management, the executive suite, vendors, suppliers and community partnerships.

Fortunately, there are a great many resources available to help nursing and long-term care facilities ensure their ability to protect patients and residents as well as staff members.

The Plan’s the Thing

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published an updated rule in 2016, “Emergency Preparedness Requirements for Medicare and Medicaid Participating Providers and Suppliers.” Health care providers, including nursing and long-term care facilities, were required to be in compliance with the new rule as of Nov. 15 of this year.

So while facilities already had disaster plans in place, CMS set the bar a notch higher and formalized certain aspects of emergency preparedness planning for the health care industry.

“Without a doubt the rule represents new challenges to long-term care organizations due to the sheer amount of work related to complying with the regulation and the preparation involved,” said Diane Doherty, senior vice president, Chubb Healthcare. But Doherty said she feels confident that most facilities were able to meet the Nov. 15 deadline.

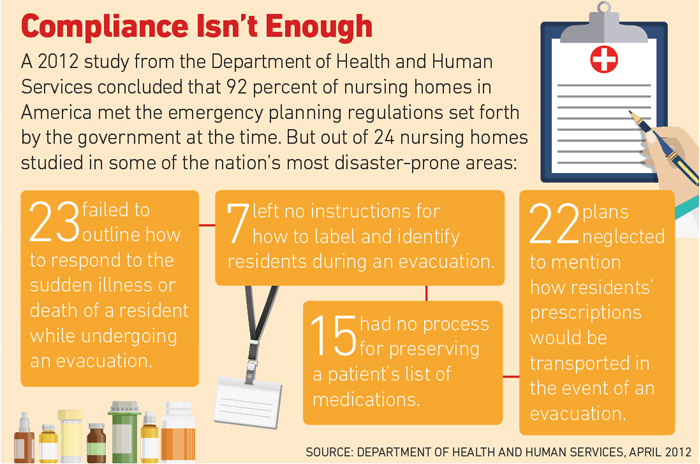

Still, there can be a significant gap between a facility that’s meeting minimum compliance requirements and a facility that’s genuinely ready to weather a storm or a sudden fire.

The foundation of a strong preparedness plan, experts agree, is a comprehensive hazard vulnerability assessment, or HVA, which looks at every type of emergency or disaster a facility might face and carefully addresses how each scenario might impact a location’s ability to keep its residents and employees safe, both during an emergency and in the days and weeks that follow.

The assessment helps pinpoint the services a facility will need by “identifying residents who require additional assistance — the wheelchair-bound, the bed-bound, the residents on ventilators,” said Doherty. This includes residents with dementia as well as those who simply need assistance ambulating.

“If you didn’t ask the right questions and don’t have the right information, it is hard to make a decision about the patient lives that are in your building.” — Scott Aronson, Director, Strategy & Business Development – Healthcare, RPA

Assessment best practices should include the help of community partners such as law enforcement and local emergency management and health department officials, said Scott Aronson, Director, Strategy & Business Development – Healthcare for RPA, a JENSEN HUGHES Company. RPA is an emergency management firm and technology provider serving the health care industry.

By engaging community resources, said Aronson, “you will at least know what they feel the threat is to your buildings and to your patients and to your infrastructure — of either getting resources in to you or getting you out of there — or whether your building will be able to stand up to the hazards.”

The quality of the assessment is key, said Aronson, because that information will help prioritize planning and support how decisions will be made during a crisis.

“If you didn’t ask the right questions and don’t have the right information, it is hard to make a decision about the patient lives that are in your building.”

For the same reason, said Aronson, organizations can’t expect their state or local government to tell them what to do in a crisis. Municipalities aren’t typically inclined to order an evacuation except in extreme situations. It’s up to each facility’s incident command team to make decisions based on the information directly in hand.

Whether the decision in the moment is to shelter-in-place or evacuate, an organization’s vendor and supplier network is a significant piece of the emergency planning puzzle.

Transportation arrangements and sheltering agreements with receiving facilities must be in place in the event of an evacuation. Fuel, water and other supplies may be needed in other circumstances. Getting it right often means having a plan B — or even a plan C.

Risk managers need to look at the larger picture — their primary and contingency vendors as well as their vendors’ contingency arrangements.

“If your fuel supply is local, for example, then do you have a contingency? Are they part of a national company where they have other resources they can bring in from other locations?” said Rick Maltz, senior director of resident services and risk management at Erickson Living, home to more than 24,000 seniors in 11 states.

Marcia Price, Erickson Living’s vice president of operations and risk management, added, “Sometimes it is necessary to make a judgment call when determining the right contract partner. You may see a vendor and it seems great — maybe the pricing’s a little lower. But if it’s a local vendor, you have to think about [your contingency plan in] an emergency. It may be better to go with a national vendor who can always provide for you.

“However, if you’re going to use a local vendor, have a backup plan or a backup contract so that you give yourself some options.”

The drawback with back-up vendors though, Price cautioned, is if you’re not a high-use client, you may not be at the top of their priority list.

Having the right supplies in the right places is a strength of Erickson’s. As Hurricane Sandy bore down on the Northeast, Erickson trucked fuel in from Florida and kept the truck parked at one of its facilities.

When nobody else in the area had fuel, they were able to keep the facility’s generator topped off and also provided fuel for employees’ cars.

New approaches are being developed that can significantly expand options for facilities and organizations of every size. More than 1,000 southern New England facilities signed on to Mutual Aid, a technology platform developed by RPA. The platform is designed to enable facilities to support each other in the event of a disaster.

Mutual Aid is a powerful tool to amplify the resources of every member facility. “They will actually deploy each other’s vendors to help the other,” explained RPA’s Aronson. “Or they’ll send their own resources and assets to help the other.”

Even for large corporate groups, such a network of support can play a massive role in terms of rapid response. A hurricane enables the advance deployment of resources, but most other disasters don’t.

“A lot of the other things corporate groups may just not be prepared for — tornadoes, earthquakes, wildfires — you can’t just plop resources down in the middle of that,” said Aronson. “You have to rely on existing partnerships in the community, in the region, and in the greater state to help you out.”

Continuous Improvement

Training and testing of the emergency preparedness plan is essential. It’s never enough to just tick off a checklist, experts agree.

“You can check the boxes pretty easily, but did you actually learn anything? And will it benefit you in the future?” said Aronson. “It’s critical that they really do it and not just go through the 10-minute motions. They have to learn from that exercise and improve their plans and training going forward.”

At Erickson Living, disaster preparedness messages are woven into the company’s broader safety education program, including department-specific safety talks, monthly town hall meetings and annual compliance training.

But it’s the drills that really test both the plan itself and each facility’s ability to execute it successfully. Drills simulate how each person might react under the pressure of a real-life crisis and help identify opportunities for improvement.

“It really helps [the facilities] train their teams on what is expected. We think that’s an important piece of being able to train people on how you handle an emergency,” said Price.

In addition, she said, it’s a chance to work with local emergency responders and solidify those relationships and expectations long before a crisis occurs.

Both Maltz and Price said that each drill and each actual incident help identify gaps. Any unexpected wrinkle is an opportunity to update the plan in order to be better prepared for the next event. “A couple of the things we learned from Harvey we took to Irma,” noted Maltz.

Price added, “Our program is based on continuous learning; it’s not an annual event because this is a living document, and we keep updating it and we keep making sure that we’re improving on it.”

Free Resources

From a coverage perspective, property and business interruption policies are essential for nursing and long-term care facilities, as are workers’ comp, medical professional liability, general liability and D&O.

But carriers have more to offer their long-term care clients, said Doherty.

“I think it’s important for [long-term care facilities] to partner with a carrier that’s going to help them meet these challenges head on, whether it’s assisting with conducting the risk assessment or providing education to their staff,” she said.

There’s a wealth of other resources out there for organizations to avail themselves of, and much of it is free.

The Nursing Home Incident Command System (NHICS) was developed in California and can be downloaded for free, said Aronson. It’s one of a large trove of free resources found at ASPR TRACIE, a double-whammy acronym for the Assistant Secretary of Preparedness and Response and Technical Resources, Assistance Center and Information Exchange.

Other free materials can be found on the websites of FEMA and the department of Health and Human Services. Numerous professional associations as well as state and federal websites offer free resources to help meet the latest CMS requirements.

“Long-term care facilities are under constant pressure to do more with less,” said Doherty. “Those that prepare and practice and train for that inevitable catastrophe — they really reduce the chances of debilitating losses while strengthening their ability to safely care for this fragile and vulnerable population.” &