2017 Most Dangerous Emerging Risks

U.S. Economic Nationalism

“From this day forward, it’s going to be only America first — America first.”

This key phrase from President Trump’s inaugural address sums up the various anti-globalization policies he intends to implement as the nation’s 45th president, which include reducing international trade, rolling back regulation enforcement and restricting immigration — all in the hopes of making America more economically independent.

But it remains indisputable that globalization has already become entrenched in the way companies do business. As one of the wealthiest and most powerful countries in the world, the United States’ economy is inextricably linked to the rest of the world.

What will economic nationalism look like within U.S. borders if these policies come to fruition, and what does that mean for risk managers of multinational companies?

Tariffs, Trade and Supply Chains

The strategy to bring jobs back to the U.S. is two-pronged: Reduce international trade through import tariffs and revitalize American manufacturing.

“Import tariffs would be enormously disruptive to supply chains,” said Bill Reinsch, a distinguished fellow with the Stimson Center, which conducts nonpartisan policy research.

“The rhetoric we’ve been hearing today shows no understanding of the complexity of international trade or the complexity of manufacturing,” said Jack Hampton, professor of business at St. Peter’s University.

“Look at Boeing Corp., with something like 50,000 suppliers. Look at the automobile industry, and all of the parts that go into making a car.

“Even if you walk into your local barber shop, you’ll look around and notice how many products in there come from overseas. It’s not just big companies that will be impacted by trade restrictions. Smaller, local businesses will suffer most. They’ll have to change their whole model of how they work.”

Imposing high import tariffs and pulling out of international trade agreements like NAFTA would raise costs and could force companies with global supply chains to find new vendors. In the short term, extra expenses will be passed on to the consumer, making everything from computers to cardigans more expensive.

For companies, the search for new suppliers always introduces some risk. Shortening supply chains and relying primarily on domestic suppliers can reduce some of that risk, said Louis Gritzo, vice president and manager of research, FM Global.

But, there’s a trade-off in how much capacity a domestic partner can provide and how fast. Shortening the supply chain must happen at a very well-managed pace or there will be a capacity issue, Gritzo said.

“A risk manager would be wise to not look at that first or second link, but also go back to where the chain is anchored to the ground and make sure they are good all the way back,” he said.

In instances when relying on a foreign supplier is unavoidable, “it’s critical to make sure you’re working with good business partners,” said Dan Riordan, president of political risk, credit and bond insurance at XL Catlin.

“Given the changing relationship between the U.S. and the rest of the world, you have to make sure you can trust your partner to help you navigate changes. Are there legal protections built into your agreement? Is there a dispute resolution mechanism, like arbitration? Because otherwise you could end up in a local court where you may not be treated fairly.”

Trade restrictions could also spark retaliatory measures, limiting potential markets for U.S. exporters.

“If you have restrictions on trade, it could lead to conflicts, and companies need to take that into account as they assess the risks of entering different markets,” Riordan said.

A New American Manufacturing

Reduced reliance on international trade calls for a boost in domestic manufacturing.

The promise looks good on paper: more self-reliance and more jobs for American workers. But the reality holds serious dangers for the U.S. economic growth.

Sparking a manufacturing renaissance isn’t as simple as following the mantra, “If you build it, they will come.” Given the high level of automation in factories, a return of manufacturing processes doesn’t necessarily translate into an influx of jobs.

“Probably one-third of workers were in manufacturing in the 1950s,” Hampton said. “Today, maybe 10 percent of workers are in factories, but they’re not doing the manufacturing. They’re fixing the machines that are doing the manufacturing.

“We went from having a few robots in the 1980s to having about 300,000 today. And one robot can sometimes do the work of 50 people.”

All of that machinery doesn’t come cheap. Manufacturers will likely need to secure financing to get all of the pieces in place. They’ll also take on more property and cyber risk as reliance on robotics progresses.

“Risk profiles will also change due to shifting claims trends,” said James Burns, head of Americas at Clyde & Co. and a member of the company’s Global Management Board. “With more business activity focused in the U.S., there will be a rise in U.S.-based claims. We have a litigious environment and high awards compared to other countries, so claims are going to get more expensive.”

Role of Regulations

To ease the burden, the Trump administration has proposed reducing regulations for American businesses: For every new rule proposed, two should be repealed. Though rolling back regulations could introduce some uncertainty for underwriters, it does open the door for more opportunity for American businesses.

“The onus is also on risk managers to understand how the rules are changing and make sure they’re still following best practices in the absence of regulation.” – Joe Cellura, president, North American casualty division, Allied World Insurance Co.

“There’s a school of thought that many EPA, OSHA and DOL regulations are administrative in nature, and they tie up a lot of resources. Reducing regulations and enforcement frees up companies to develop their own processes internally and direct resources as they see fit,” said Joe Cellura, president, North American casualty division at Allied World Insurance Co.

But regulations often are created to reduce risk for businesses. If the regulation goes away, some risk comes back, Gritzo said. Maybe not right away, but with a lack of oversight in some key areas of safety and loss prevention, those risks may start to creep up again and result in unintended losses.

Underwriters also rely on federal regulations to provide a consistent risk management framework.

“The current regulatory environment can be a friend to underwriters in the areas of workplace safety and workers’ compensation, product quality and safety, and environmental liability by creating a consistent compliance framework for all companies to follow. If that goes away, the onus is on us as underwriters to be even more aware of who we’re insuring and how they’re operating,” Cellura said.

“The onus is also on risk managers to understand how the rules are changing and make sure they’re still following best practices in the absence of regulation.”

Luckily, the best risk managers understand that adhering to high standards is as much about good business as it is about compliance.

“Our best customers are those who treat federal regulations as the minimum operating standard. And that’s not likely to change even if enforcement changes,” he said.

Immigration Restriction

U.S. protectionism doesn’t just apply to economic policy. Cracking down on immigration, both legal and illegal, is a major agenda item for the current administration.

Immigration actions to keep illegal immigrants out and deport those already here have interrupted legitimate visa processes and threaten to restrict travel altogether from a handful of countries.

Implementation of these policies in turn engenders an exclusionary, anti-foreigner attitude.

Supporters of immigration restrictions believe more resources will be targeted to current, taxpaying citizens. But keeping people out could have significant long-term effects on the American economy.

Tech industry giants have already expressed concern that limiting immigration will shrink the talent pool and lead to less diversity, though there’s debate around that claim.

“Some say there’s plenty of talent within our borders already, and that immigrant workers gain favor simply because they’ll work for less,” said Reinsch of the Stimson Center.

It’s not just the current talent pool that could be imperiled. Ripple effects may be felt from fewer international students attending American universities.

“I’ve heard several university presidents express concern. International students typically pay full freight, which frees up more financial aid and effectively subsidizes education for American students. So universities could face financial problems if they lose that base,” Reinsch said.

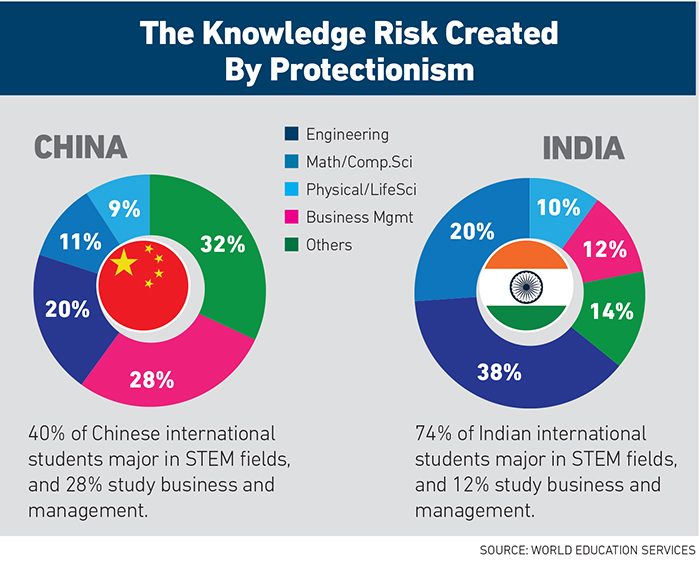

According to data collected by World Education Services, 40 percent of Chinese international students major in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields. For Indian students, it’s a whopping 74 percent.

Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that more than half of all advanced STEM degrees are earned by international students. Meanwhile, the number of U.S. citizens and permanent residents earning graduate degrees in science and engineering fell 5 percent in 2014 from its peak in 2008, according to survey data collected by the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

What will be the long-term impact to our science and technology industries if these international students stop coming here, especially if engineers are more critical to the success of manufacturing than factory line workers?

What will be the long-term impact to our science and technology industries if these international students stop coming here, especially if engineers are more critical to the success of manufacturing than factory line workers?

“We could see more students going to Australia, the UK or Canada for English-language education. So many of our best engineers come here on visas to study. It’s not just from India, but from a lot of countries that the administration may want to block,” Hampton said.

“That could have effects later on if the U.S. starts to lag in technology.”

Even when international students don’t stay, the U.S. benefits when they return home with an American education and a sense of American values.

“They take our value system and culture with them, and perhaps become a voice in their country for human rights and rule of law,” Reinsch said.

“You can’t quantify the effect of that. But I think it’s to our advantage to have thousands of Chinese students go back to China every year and take our Western culture with them. Without that, it drives our countries further apart and makes dialogue more difficult.”

Reinsch pointed to intellectual property protection as an example. One of our biggest challenges with China, he said, is IP theft and lack of respect for trademarks and patent laws. Chinese students may return home with a stronger appreciation for IP protection, because they worked with U.S. universities who benefit very much from strong IP laws. If those students go on to create or invent something, they’re more likely to demand stronger protections from their government.

“The Chinese government has … made some progress in IP protection. That benefits China more than anyone else, but it helps American companies too because it at least creates a judicial process if there’s a dispute,” Reinsch said.

Similar to retaliatory trade tariffs, restricting immigration could lead other governments to tighten their own laws to make travel more difficult for Americans. Iran has already promised to block U.S. citizens from entering the country in response to President Trump’s proposed travel ban on several Muslim-majority countries.

What if more nations follow suit? What if further conflict threatens the visa waiver program among the 30-plus countries that currently allows ease of travel for business, education and leisure? Travel restrictions make it harder to do business, limit research opportunities and make it difficult for countries to work together.

Nonetheless, Hampton of St. Peter’s University trusts that risk managers have grown adept at preparing for business disruption.

“Disruption mitigation has become highly developed. I suspect risk managers have been preparing for disruption since the November election.” &

________________________________________________________________

2017 Most Dangerous Emerging Risks

Artificial Intelligence Ties Liability in Knots

Artificial Intelligence Ties Liability in Knots

The same technologies that drive business forward are upending the nature of loss exposures and presenting new coverage challenges.

Cyber Business Interruption

Cyber Business Interruption

Attacks on internet infrastructure begin, leaving unknown risks for insureds and insurers alike.

Foreign Economic Nationalism

Foreign Economic Nationalism

Economic nationalism is upsetting the risk management landscape by presenting challenges in once stable environments.

Coastal Mortgage Value Collapse

As climate change drives rising seas, so arises the risk that buyers will become leery of taking on mortgages along our coasts. Trillions in mortgage values are at stake unless the public and the private sector move quickly.