This One Change Improved Outcomes Tenfold for Travelers’ Workers’ Comp Claims

Want to keep your workers’ compensation claims from sliding off the rails? Start with case managers and claims adjusters who look, think and talk like their clients.

Four years ago, Travelers started its Cultural Advantage program. The program hires Hispanic adjusters and nurse case managers to more closely mirror the populations it serves. The initiative produced a 24 percent improvement in injured workers returning to work within 30 days and a 23 percent reduction in attorney representation, said Chris Nixon, senior vice president, claim field management, Travelers.

Often, he said, the conversation begins in English, and as the rapport develops, the injured worker or case manager will ask, ‘Do you speak Spanish?’ “When the response is ‘Yes,’ the conversation transitions into Spanish, and the connection flows from there.”

In Travelers’ Southern California office, a third of claims and case professionals are bilingual, he said, and most speak Spanish, but the program seeks to establish “a cultural connection beyond simple language translation” by matching case and claims managers with injured workers from a similar language and culture.

“Sharing a background provides a more personal connection,” he said, which is a “key to establishing sincere upfront trust.”

All About Trust

The success of a claim depends on trust between the client and case manager, said Jose Alejandro, director of care management, UC Irvine Health and president-elect, Case Management Society of America. In his 25 years in health care, he said, “claims seldom go to litigation when that relationship is trusting, open and collaborative.”

Trust depends on common language and cultural understanding, if not actual common culture, Alejandro said. If a case manager or claims adjuster tells an injured worker “these are the three things I need you to do,” he said, that command — an emotionally neutral statement when the case manager and injured worker understand and trust each other — could be received as officious, bullying or arrogant if issued without medical context or regard to cultural considerations.

The worker, offended and confused, could refuse to cooperate. “What should be quick and easy could then take a long time and use a lot of resources.”

Darrell Brown, chief claims officer, Sedgwick, breaks down what “trust” means in the workers’ compensation context. “Manage expectations about the process and how long it will take. Establish what to expect from the client and what the client can expect from us. Understand the family’s needs.”

Which means, he said, address the urgent financial and logistical worries during convalescence: How will I pay the rent? Buy food? Make car payments? Get the kids to school?

Those concerns can be overwhelming, especially for people who already feel marooned in a strange and perplexing world where they don’t speak the dominant language.

“Nurse case managers and claims examiners need to be able to hold clients’ hands through the process, navigating around barriers and interpreting the strange rules,” Brown said.

Alejandro, who holds a nursing degree and was once a claims manager himself, recalls when his own Hispanic cultural experience rescued a two-year-old workers’ compensation claim for a burn to the claimant’s hands and arms. The claim had exhausted all appeals — and the multiple claims managers who had already tried and failed to set it right.

Alejandro flew in to meet the client. After going with her to medical appointments and speaking to the claims manager, he located the disconnect: miscommunication about the outcome the physician wanted, what the claims manager wanted her to do, and what the client understood them to say.

“No one was on the same page,” he said.

“[Good diversity training] sets the expectation that groups are different, that you can’t expect a good outcome when you treat everyone the same. A broken leg isn’t just a broken leg.” — Jose Alejandro, director of care management, UC Irvine Health

Part of the problem was language. “Hiring a translator didn’t bridge the gap between speaking and medical language around prognosis, protocols and timeframes,” Alejandro said. “She was extremely frustrated about not being able to understand the medical pieces and how they impacted her quality of life and return to work.”

She also felt intimidated by the doctors and case managers, who seemed to hold all the power and who failed to adequately explain why they were asking dozens of personal questions.

Alejandro collaborated with the physician and claims adjuster on a treatment plan. “We broke the process down and walked through it again, slowly at first” while Alejandro worked to win the client’s trust, which wasn’t assured despite their cultural similarities. Within 190 days, she returned to work, not pain-free, but pain-managed. “That’s what she wanted, to return to work.”

The eventual success, he said, depended on a functioning triad model: health care providers, claims adjuster and claims manager working with the client to get through the process. The missing ingredient, before his assignment to the case, had been a claims manager capable of understanding the client’s language and representing her expectations and desired outcome accurately.

1:1 Cultural Match Not Necessary

While similarity between large and disparate cohorts — Hispanic to Hispanic, African American to African American, for example — can grease the communication and cultural wheels, an exact match — Portugese to Portugese in an area with a small Portugese population, for example — is often neither practical nor necessary.

Diversity and inclusion training, including a deep dive into the culture and demographics of its clients, helps bridge the gap, Brown said. “When I call a bank or airline, I’m looking for the most capable person to help me,” which isn’t necessarily a cultural match.

Good diversity training, said Alejandro, addresses the principles of working with different groups, regardless of what the group is. “It sets the expectation that groups are different, that you can’t expect a good outcome when you treat everyone the same. A broken leg isn’t just a broken leg.”

Travelers takes training seriously, said Fred Colon, chief diversity and inclusion officer, starting with a commitment from top leadership. A robust program that produces measurable results in duration of claims, reduced litigation and claims spend, he said, involves a lot of time, thought and resources.

Travelers commits a half-day workshop with live trainers at every employee’s hire, and the principles the training covers affect every aspect of the company’s brand, recruitment, professional development and retention.

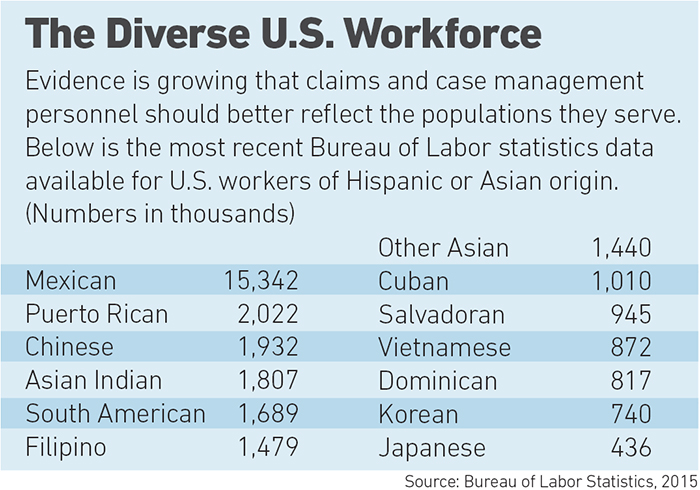

Although Travelers’ bilingual hiring concentrates on serving Hispanic-Americans, the country’s largest minority at nearly 60 million, according to a Simmons Market Research survey, training “should capture diverse religions, geography, location, cultures, sexual orientation and political points of view, among other things,” said Colon.

Even the most diverse claims and case management populations need training, said Brown, the executive sponsor of Sedgwick’s inaugural diversity and inclusion council. He describes a soul-baring aspect to its training.

Sedgwick’s very diverse workforce “has a lot to teach each other” about unconscious bias, Brown said. “I thought I was open-minded and empathic, but there was so much I didn’t know about what working mothers deal with, taking care of children, among others.”

Working mothers are just one of the groups that can evade many people’s radar screens. “You need all those voices at the table to bring their experiences and perspectives,” Brown said.

That personal revelation ties directly to claims outcomes, he said. Anything can go wrong: the patient doesn’t like the doctor, doesn’t agree with the return-to-work plan, skips appointments. Payment may be delayed for perfectly legitimate reasons.

“Appreciating differences makes you a better case manager. Workers litigate because the process is foreign and they fear termination,” he said. “We have a role in mitigating that. We put our understanding of differences to work.” &