Transportation

Staying on Track

A side effect of the oil and gas boom has been a spike in the number of rail tanker oil spills. In many cases, outdated tracks are the culprit.

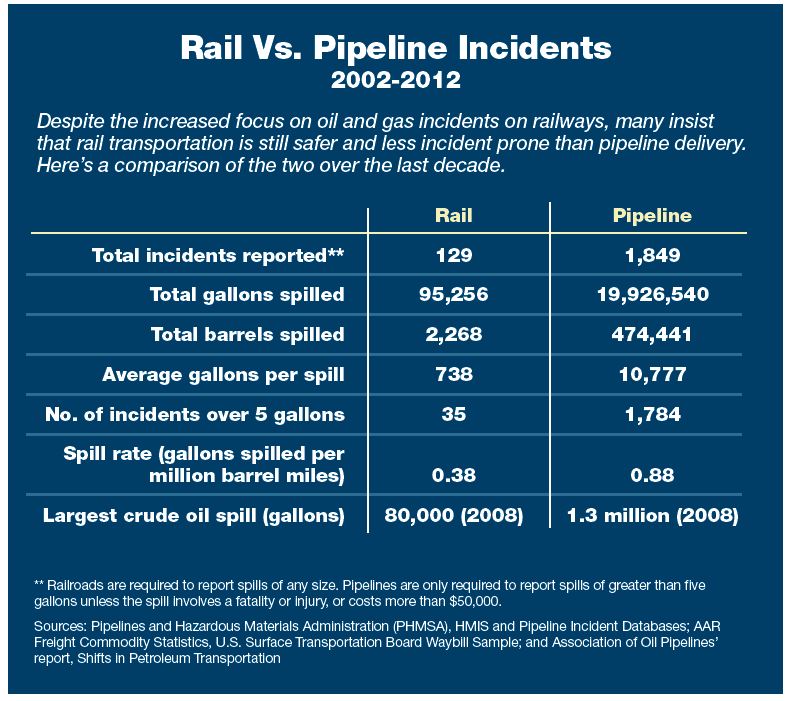

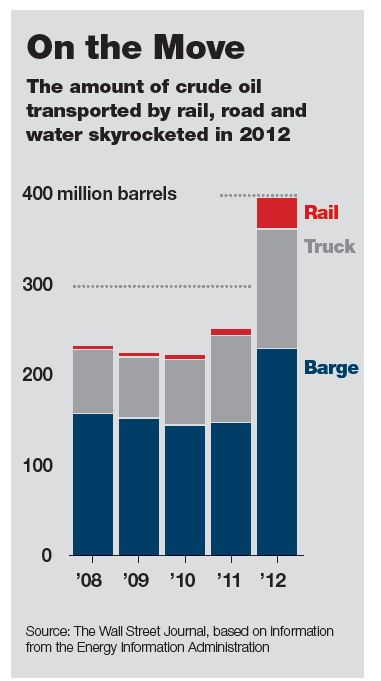

Domestic oil production is on the rise — and with it oil spills from rail cars, as producers use alternative methods to deliver their product in the absence of pipelines.

The latest spill to make international headlines occurred in June, when a freight train carrying crude oil exploded in flames in the Canadian town of Lac-Megantic, killing dozens and destroying more than 30 buildings.

Railroad and oil companies that lease rail cars can lessen the chance for spills from both slow leaks and sudden derailments or collisions, by increasing inspections and adding protective measures during loading and unloading at stations, experts said. Moreover, all parties involved can better protect themselves by obtaining certain coverages within their insurance program.

U.S. rail companies reported 112 oil spills from 2010 to 2012, compared to just 10 spills in the previous three years, according to the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

Jim Beardsley, managing director, Marsh Global Rail in Washington, D.C., said that most spills happen during railway accidents such as collisions, derailments or overturns, while slow leaks from faulty cars are less frequent or severe.

“There are inspections at every point, from loading the oil onto the train to moving it to another railway to unloading,” Beardsley said. “While on the train, it’s not impossible, but very unlikely, for product to spill out because of equipment failure.”

For spills due to sudden accidents, part of the problem is that some tracks in areas such as Montana, Canada and the Bakkan Formation in North Dakota, weren’t in frequent use before the recent oil and gas production boom and are now subject to heavy volume, said Ron Mathewson, Rail Casualty Underwriting manager, Specialty Products, Zurich North America Commercial in New York City.

“The unit trains transporting crude oil can get up to a mile in length — that’s a lot of wear and tear on these tracks,” Mathewson said. “It’s up to the railroad to make sure that the tracks are up to snuff. Specifically, an underwriter wants to know how much money is spent per track mile.”

Carriers like Zurich that offer insurance coverage for rail transport also want to know how a railroad is controlling “the human element” — engineers and conductors — whether they are operating the train safely, following speed limits and paying attention to signals.

The third issue underwriters consider is the “rolling stock” — pressurized tank cars. In a situation when a railroad picks up a car owned or leased by another company, the railroad is required to inspect the car. If the tank car fails inspection, the railroad sends it out for repair.

“It can be a real challenge to adequately inspect a mile-long train,” Mathewson said. “For our book of business, we haven’t seen crude derailment spills, but it’s something we’re keeping our eye on. Our typical clients are in the short line rail space. They tend to move slower, with less chance for derailment with catastrophic spills.”

Emergency Response

When a derailment happens, Zurich provides an online environmental claims spill report process, so companies have the ability to report emergencies and initiate a response program immediately, said Christopher Hagerman, Zurich’s emergency response coordinator. This can reduce their environmental liability and exposures and, as such, their damages and costs.

The program, free to clients, provides emergency response coordination services, technical resources and access to Zurich employees who have subject-matter expertise, as well as verbal and regulatory reporting, Hagerman said. A Zurich emergency response coordinator facilitates communications between the customer, the regulators on site and the emergency response contractors and consultants responsible for mitigation of the emergency.

“It takes a massive response to coordinate with local, state and federal officials,” he said. “We have to make sure our insureds are sitting down at the table and talking with us as their insurance carrier, and that consistent lines of communications are established with regulatory authorities to make sure the spill is being handled efficiently and effectively.”

Robert Fronczak, assistant vice president, Environment and Hazmat, for the Association of American Railroads (AAR), said that railroad companies annually train about 30,000 emergency responders, either internally or through the American Chemistry Council’s Transportation Community Awareness and Emergency Response program. Moreover, railroads sponsor training for local emergency responders.

However, reducing the risk of spills starts with preventing accidents in the first place, Fronczak said. The association annually invests more than $13 million on railroad safety and efficiency research, and the Federal Railroad Administration spends even more. Such research is primarily conducted at the association’s Transportation Technology Center in Pueblo, Colo.

“Examples of some of the research that is going on there includes evaluation of safer track and bridge components, the evaluation of better ways to inspect track to prevent rail-caused derailments, and the use of wayside detectors to detect defects on rail equipment,” he said. “Railroads also conduct research in fatigue management to help employees deal with fatigue on the job.”

Railroads are also active in implementing “positive train control” — technology that monitors the location of all trains within a system, with the goal to automatically stop trains before collisions if their crews do not, Fronczak said.

The association has also helped to produce standards for the construction of crude oil and ethanol tank cars, which has significantly lowered the probability of product release to about 18 percent.

Fronczak said the preventative measures are working: Train accidents and accident rates in 2012 fell 16 percent and 19 percent, respectively, from 2011, according to Federal Railroad Administration.

The trade group also works to reduce “non-accident releases,” (NARs) typically caused by rails cars not being properly secured at point of origin, he said. Since the inception of the NAR Task Force in 1996, such leaks have been reduced by 49 percent. Moroever, AAR recently revised its Pamphlet 34 — “Recommended Methods for the Safe Loading and Unloading of Non-Pressure (General Service) and Pressure Tank Cars” — to assist shippers in the proper procedures for loading and unloading.

The NAR Task Force “constantly” looks for ways to reduce such leaks by collecting and evaluating data, Fronczak said.

“The Task Force is looking at hardware that can be implemented or improved upon, as well as improvement of processes used in the loading and unloading of tank cars, and communicates issues identified as a result of their activities,” he said.

Covering All Angles

Regarding insurance, most casualty programs for railroad companies have sudden and accidental environmental coverage, so railroads don’t often purchase specific standalone pollution coverage, said Thomas Swartz, senior vice president with Marsh’s Environmental practice in Houston.

“There can also be gradual leaks, but they are generally not insurable through casualty programs,” Swartz said. “These leaks are typically of a smaller size and magnitude, and while they can build up over time to larger issues, most railroad companies generally assume these risks within their self-insured retention, choosing not to purchase environmental liability coverage.”

While the casualty programs will often respond to over-the-rail sudden and accidental events, the loading and unloading operations may not be the responsibility of the railroad company — which can potentially expose the tank car owner or the owner of the product to liability from spills during transloading operations, he said.

The companies that own the product or tank cars may choose to insure the loading and unloading portion of the risk with a specific environmental policy, often called a pollution legal liability policy, Swartz said.

This type of policy also provides contingent liability coverage for over-the-rail spills in the event that the product owner is sued directly for damages from a spill. Furthermore, pollution legal liability policies don’t generally exclude gradual pollution events, offering the insured broader coverage than is available through traditional casualty programs.

Oil companies purchasing transportation coverage must specifically request that “rail” and “rolling stock” be added if their carrier does not include these terms in the definition of transportation, said John Welter, executive vice president and managing director of Aon’s Environmental practice in Houston.

“Derailment spills make news because they are big releases and catastrophic, but over time a line or coupling became undone and oil spills to the ground,” Welter said.

“That happens more frequently, so oil and trucking companies will want to make sure their carrier’s definition of transportation includes loading and unloading.”

While regulators are increasingly scrutinizing the use of rail cars and pipelines to transport crude, more carriers today are providing environmental insurance than before, he said.

“The underwriting process might be tougher because of increased scrutiny and publicity, but coverage is still readily available,” Welter said.