Agribusiness Risk

Risk Rises in Wine Country as Weather Becomes Increasingly Volatile

The wildfires that raged through premium wine-growing regions in California’s Napa and Sonoma counties proved a pressing point: Climate change is taking aim at vineyards.

The wine industry is taking a hit as global temperatures continue to rise, according to an Allianz study that says many prominent vineyards in California, France, Spain, Portugal, Australia and South Africa will experience heat too hot and dry to produce quality wines by 2050.

“Climate has always had a hand in how wine is made,” said Brett McKenzie, Allianz’s agribusiness Midwest zone leader. “It would be unwise not to adapt to climate.

“However, winemakers hit by climate might not think about the types of insurance needed. They might not be educated in risk management and insurance,” she said.

“When you look at vineyards and wineries, you have farming risks, manufacturing risks, retail risks and hospitality,” said Larry Chasin, president, Winery PAK Insurance Programs.

“Weather is a risk we all seem to be facing these days.”

Weather and the Vine

Wine is one of the world’s long-lasting crops — the oldest recorded vineyard was found in an Armenian cave dated circa 4100 BC. Winemaking, then, has survived the tests of time. So if wine is such a survivor, what makes today any different than the past?

“Climate change has a greater impact on fruit development and vintage effect, variations on yield and quality,” said Chasin. “Heat has led to early harvests, which effects the ripening of the fruit.”

“Think of a raisin: It’s a grape exposed to too much sun. It shrivels up and gets sweet. A grape on the vine exposed to too much sun will go through the same process,” said McKenzie, which may not be what a vintner set out to grow in the first place, affecting crop, yield and quality.

Additionally, Jose Gutierrez, senior risk management consultant, ICW Group Insurance Companies, added, “Because of the heat, the increase of pests and fungus may also contribute to both evolving short- and long-term risks for the product.”

Climate change has been tracked and monitored by scientists for decades with the majority of experts agreeing temperatures are on the rise. And from changes in temperature come natural disasters.

Water deficits and droughts, hail, flooding, the frequency of extreme weather events all influence the way a grape is grown. With increasing volume, natural disasters plague the wine industry. In the last year alone, vineyards in prime winemaking countries faced sudden frosts, high-magnitude earthquakes, extreme droughts and more.

“Pollution and wildfire are two big exposures,” said Chasin. He pointed to the recent wildfires that engulfed California and other mid-western states.

Look at the language, he said. Reports called the fires unprecedented in terms of behavior, speed and velocity.

The focus is on life safety — and rightfully so — but Chasin added that, much like tornadoes, these fires could hit one property and not the one next door. They’re unpredictable and could cost vineyards millions.

Chasin and his team visited the area in mid-October, assessing damages and helping where they could.

“The fear was real,” he said. “I don’t know if anyone’s ever seen something like this before.”

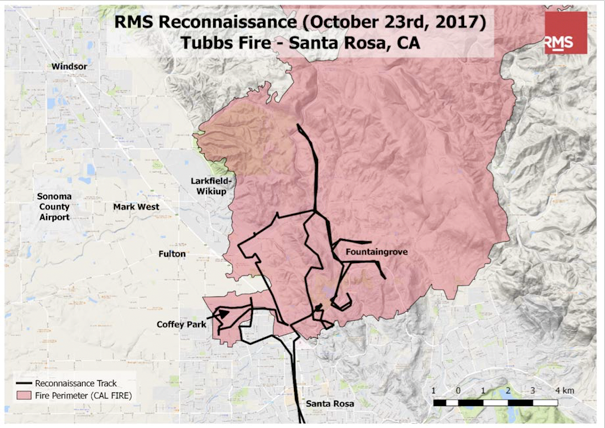

RMS reconnaissance experts were able to visit the area in late October as well, updating the total economic loss estimates between $6 billion and $8 billion. This estimate included loss due to property damage, contents and business interruption caused by the fires to residential, commercial and industrial lines of business.

As of October 20th, the fires burned more than 245,000 acres in the premier grape growing regions of Mendocino, Sonoma and Napa counties. Forty-two people were reported killed and hundreds more missing, and more than 5,700 structures — homes and businesses — were damaged or destroyed.

RMS noted that ember risk, driven by extreme Diablo winds, contributed to the overall damages done to the exposed area. Vineyards, according to Wine Spectator, acted as breaks for the raging wildfires, however, which kept the losses low in many cases.

“Weather is a risk we all seem to be facing these days.” — Larry Chasin, president, Winery PAK Insurance Programs

Still, some vineyards were destroyed while others had partial damage. In the short-term, said Chasin, wineries have lost business during the busiest time of the year — harvest season. In the long-term, these vineyards will feel the repercussions of the fires when it comes time to sell vintages from 2017.

“In two to three years from now, some will have no wine to sell,” he said.

Vintners, however, are unlikely to move away from such at-risk locations. Where a grape is grown affects yield just as much as proper sunshine and water. When looking at where to plant their vines, vintners look at the soil quality and how it affects the taste of a grape — or, as winemakers call it, the terroir of the region.

“One grape growing in Canada versus the same grape in California will taste different,” said McKenzie.

She provided the example of a Sauvignon Blanc produced in Bordeaux versus a Sauvignon Blanc from New Zealand. The Bordeaux, she said, will have a grassier taste while the New Zealand yield will have a lemon zest/citrus quality.

“It’s the same exact grape but can taste very differently.”

This happens due to the minerals found in soil. That’s why volcanic regions, coastal regions and areas found on fault lines attract winemakers to take root, posing the question: If a breezy shoreline is good for the vine, how will the wine industry compete with beach homes and other citizens inhabiting the coast?

Fighting Climate’s Wrath

But winemakers are tackling one risk at a time. To combat the adverse effects of weather, McKenzie said organizations that promote winemaking in each region are talking to each other about processes to mitigate losses in their regions, whether those losses stem from pollution, climate, labor and so on.

“Wineries are thinking about their portfolio mix,” she said. If a grape isn’t growing well due to climate and weather factors, vintners should think of the long-term effect that might have on their product. “Get creative in your strategy. Ask yourself ‘are my grapes the right mix long term?’ ”

Some winemakers are already thinking outside the box. It’s not uncommon for a winery to receive grapes from various vineyards, committing their efforts to blended wines instead. This, in some cases, keeps vineyards thriving — in other places it’s creating animosity.

More vineyards are embracing technology as well.

“We’re seeing more weather-based technology monitoring moisture and heat. More sophisticated climate measuring technology,” is making its way onto vineyards, said Chasin.

This technology assists during harvest and fermentation.

Outside the actual growing and cultivating process, hotter weather, said Gutierrez, could lead to higher incidences of heat illness among the labor force, affecting workers’ compensation claims. To combat heat, “Wineries are requesting that the grapes be harvested in cooler weather. So, when average daytime temperatures in the area are 100+ degrees, some vineyards are beginning to harvest at night.

“In some instances, during the hotter periods of say August and September, there are vineyards that begin harvesting at 11 pm and go until 7 to 8 am,” he said.

Other Risks

While implementing new techniques to combat weather-related risks is a smart thing to do, the practice opens vintners to additional exposures.

For instance, vineyards harvesting at night “need to develop a night-harvesting program that includes high visibility vests, ambient field lighting and personal employee lighting, and communication procedures,” said Gutierrez.

Nighttime harvesting not only shields workers from the heat, but it also pits them against nocturnal safety hazards — lowered visibility, nocturnal animals — which could impact workers’ compensation claims.

Likewise, as more growers turn to technology to combat rising temperatures, they leave themselves open to potential equipment breakdown.

“Thus the risks associated with machinery increase,” Gutierrez added.

In terms of weather, cyber can also pose risk. Climate measuring technologies connected to the internet are susceptible to hacking. Once inside the equipment, there’s no telling what a hacker will do.

“We’re starting to learn that hackers can get anywhere anytime they want,” Chasin said.

In general, “cyber is a big one affecting vineyards,” said Chasin. Many wineries, he said, have wine clubs where members of the community subscribe to have packages of wine sent to their homes throughout the year. Wineries take and keep credit card information on file, a risk affecting both winemakers and their customers. If a vendor is hacked, they are liable for their consumers’ information on top of regular business operations.

The risks don’t stop once the grapes are picked and packaged either.

Vineyards are hot-spots for weddings, tourism and other such events. Public exposures like walking paths and parking lots open a vineyard to liability for public injury. Wineries are also responsible for the safe transportation of their product, even when using a third-party vendor to transfer bottles to a warehouse.

“A winery needs to have coverage for wine in transit and while at the storage location,” Chasin said.

“When you’re in wine territory, there are service providers dedicated to transporting wine to dedicated warehouses. Wineries need a written agreement specifying liability” if there is a loss during transport and storage.

Building a Risk Management Plan

There exists a slew of potential liabilities a vintner needs to consider when creating a risk management program, from increasing temperatures and natural events to walking paths and thievery.

McKenzie suggests winemakers looking to build up their risk management team find an insurance broker or agent who specializes in wineries and vineyards. In other words, “Get someone who understands the coverage for anything ancillary to your operations,” she said.

Brokers, insurers and risk managers educated in the wine industry are key components to a successful team, Chasin said. “Stick with specialty insurers. [Vintners] need to communicate with their broker as their business changes; it’s not a set-it-and-forget-it practice. They have to keep brokers up-to-date with changes.”

“Purchase proper limits,” he added. “Undercutting your limits doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

“Think of everything,” said Gutierrez. “Hope for the best and prepare for the worst. Last month’s tragic fires in northern California point to the importance of having an emergency action plan in place.

“While there are a lot of unknowns at this point, it’s worth mentioning that the rebuilding of these operations will pose new hazards and risks as businesses start to dismantle and rebuild their facilities as a result of the fires,” he said, stressing the importance of the risk management team in this time of rebuilding.

And the good news: The wine industry is unlikely to disappear anytime soon — wine consumption reached 24,707,701 liters worldwide in 2015, according to the Wine Institute. Insurers are prepared to protect wineries in a world of changing climate.

And although grapes and structures were lost in the October fires in California, many of the gnarly, tough-stemmed vines will survive, experts predict.

Even in a bad year, McKenzie said, it’s not as bad as it can get — experienced winemakers know how to work with changing temperatures and the disasters that stem from those changes. &