Local Supply Initiatives

Risk Management Mentors

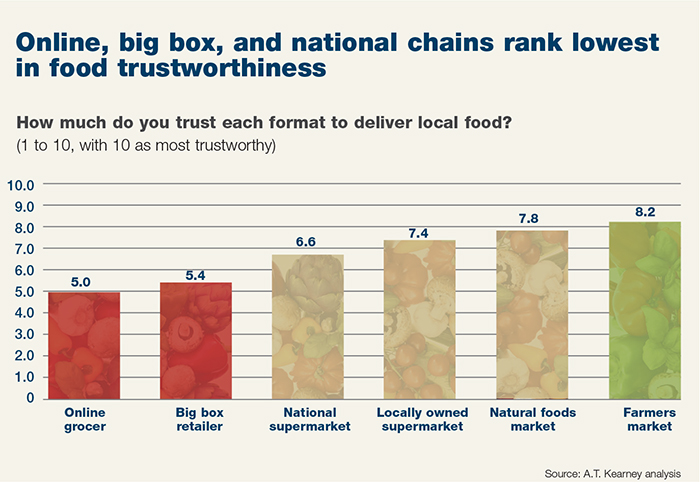

Small is beautiful in terms of locally produced food. It is also big business, and grocery-store chains are making their supply chain and risk management process more flexible and innovative as they compete against street-corner markets and local retailers.

A report from the Food Marketing Institute indicates that between 2012 and 2013, three-quarters (76 percent) of all supermarkets added more locally supplied items. Interestingly, for independent grocers an even greater percentage, 92 percent, said they did so.

It was several years ago, said Rod Parker, general manager for E.A. Parker & Sons in Oak Grove, Va., that big grocery chains began “the push” to have local produce in their stores. Parker Farms processes, inspects and ships fresh-grown produce to major retail and wholesale outlets.

At that time, he said, “there was a big question about who would be able to play and who would not among growers. We decided early that we wanted to play, so we did what we had to [related to insurance and risk management programs]. It was expensive and difficult, but we did it.

“Our liability insurance has gone up from $2 million to $5 million to $10 million,” he said, noting that the organization did not need much help in attaining the insurance it needed.

“Grocery stores and the big-box retailers, especially those with a house brand, want to push the recall exposure down as far as possible.” — Florian Beerli, senior vice president of product recall, ACE Westchester

Citing competitive reasons, Safeway — widely considered a pioneer in this area — declined to talk about its local supply initiatives or the risk management programs behind them.

So, too, have other large grocery companies.

Industry experts said that Publix and Kroger have also made strides in this area, but both companies did not respond to inquiries. Whole Foods, another heavy promoter of local supply, has a policy of not talking to the trade press.

Walmart, in contrast, is considered a laggard in local-supplier outreach. That company made reference to an in-store merchandise-tracking device, but refused to discuss its supply or risk management.

The irony of the official reticence is that supply-chain and risk managers at several of those chains are reportedly exceedingly proud of how their companies have retooled after their initial efforts met mixed results.

“When we and other groups first wanted to stock local products, the supply-chain methodology at the time led us to say ‘no’ a lot,” said a food industry risk manager who asked to remain anonymous.

“Now, our methodology and those of a few others is to find a way to say ‘yes.’ ”

Formalizing Procedures

Sam Lefore Fruit Farms, a family owned farm in Milton-Freewater, Oregon, has been supplying tree fruit to Safeway grocery stores for more than half a century.

“We also work with some independent buyers, but mostly Safeway,” says farm owner Sam Lefore. “We have always had a very low rejection rate, and we carry all the levels of insurance that they prefer.”

“We also work with some independent buyers, but mostly Safeway,” says farm owner Sam Lefore. “We have always had a very low rejection rate, and we carry all the levels of insurance that they prefer.”

Over the past few years, Safeway has formalized its insurance and safety practice requirements, he said. “They got very serious and very organized. We pay for the auditors that they send, and meet with them annually and go over the score sheet.”

Safeway’s website provides some details about its local produce initiative as well as some supplier profiles.

In April, the company released its “Supplier Sustainability Guidelines and Expectations For Safeway Consumer Branded Items.” Those guidelines require, in part, that suppliers will:

• Favor domestic/local production where feasible;

• Implement measures to secure the supply chain;

• Comply with all applicable environmental regulations and laws in the areas they operate;

• Practice humane treatment of animals;

• Strive for “grass-fed,” “cage-free,” “no antibiotics administered,” certifications; and

• Focus on environmental health and safety internally and externally.

Initially, experts said, most big chains demanded the same high levels of insurance coverage and third-party auditing that they did for their major suppliers. Few local suppliers had the time, money, or staff to comply, and were shut out.

At the other extreme, some chains took local suppliers at face value, and accepted any liability as their own.

Neither situation made anyone happy, so a new collaborative approach evolved.

“Some products are inherently safer than others,” said the risk manager. “Salsa is one thing, spinach is entirely another. We first determine what is the inherent risk, then see what insurance and risk management the supplier already has. Sometimes, they are good and sometimes they are short.

“Next, we see what would it take to bring the supplier up to the proper levels, and if it is worth our while to work for that. If so, we consult on their processes, and may even recommend them to a broker to place additional coverage. It’s all very individualized,” the risk manager said.

Product Recall

“We are starting to see more of a thought-out approval process that includes insurance minimums, in which we have been helping the suppliers or co-packers,” said Florian Beerli, senior vice president of product recall at ACE Westchester, the company’s U.S.-based wholesale business.

While he couldn’t discuss specific grocery-chain referrals of suppliers, he said that product recall was a big emphasis and that “business in the recall market [is] being more and more contractually driven.”

“Grocery stores and the big-box retailers, especially those with a house brand, want to push the recall exposure down as far as possible,” but he noted there are practical limits to such an approach.

“There are various solutions. The most common recall limit is $5 million, although some stores do require $10 million regardless of the size of the supply contract. Some of the well-known brands buy their own coverage and require their co-packers to buy coverage to the self-insured retention (SIR).

“Others buy coverage on behalf of the co-packers, then have them cover the SIR. And recently, some big brands are trying to put together group coverage for their suppliers,” he said.

For its own part, ACE focuses on the first-time buyers, so it is at a good vantage point to see the quick evolution of this sector.

“We have adopted a tailor-made approach in which we have base wording in the contract, and then everything else is added by endorsement,” Beerli said.

That puts the onus on the carrier’s underwriters, but “holding hands with the first-time buyers” is what Beerli said his firm does.

It also enables the company to conduct the education that he believes is also necessary.

“There is still work to do about recall protection,” he said.

Reputational Risk

Balance is the word used most often by Thomas Pegg, deputy director of casualty risk control at the Willis Group.

“Grocery stores are attempting to work more closely with local suppliers,” he said.

“They have found they need a bit more flexibility on contractual risk transfer, but that is very product specific.”

The need for balance in risk management is not just external, based on what is feasible with small suppliers, it is also an internal challenge, he said.

“I know of no other area of concern to these companies above brand protection from reputational risk,” Pegg said. “They have very high standards.”

That mandate could be most easily met with heavily processed, hermetically sealed products from other large corporations.

That mandate could be most easily met with heavily processed, hermetically sealed products from other large corporations.

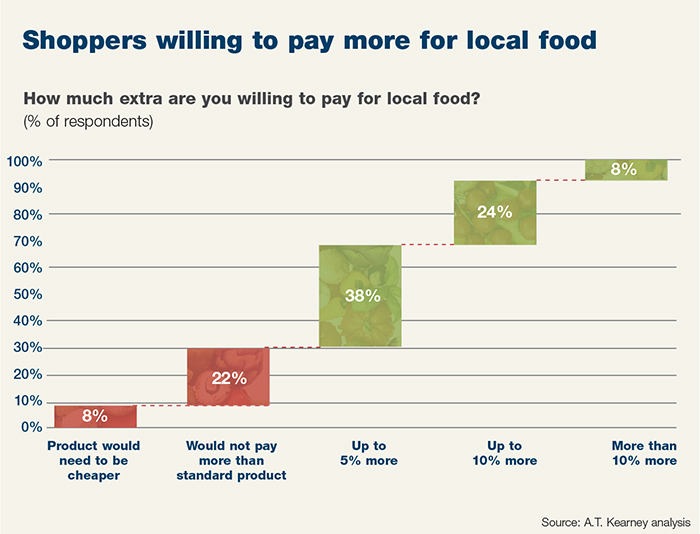

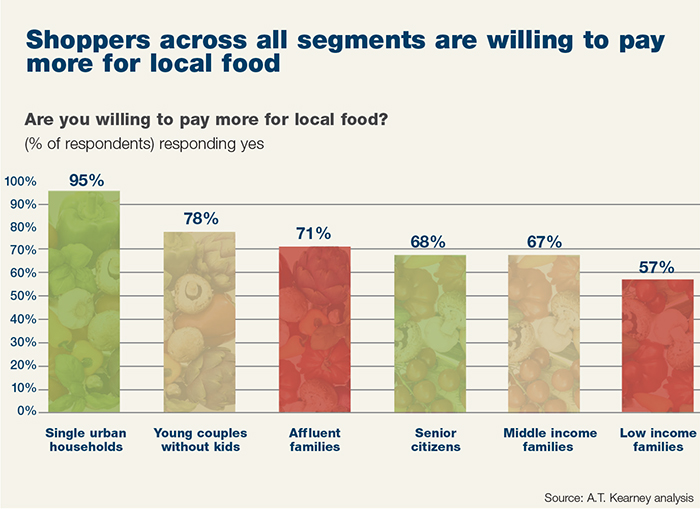

But consumer buying habits prove that they want knobby heirloom tomatoes and corn with clods of dirt still on the stalks.

More to the point, they are willing to pay more for local produce. Hence, the need for a nuanced approach.

Pegg said that some grocery-store clients have supported their local suppliers in Pennsylvania to achieve the food-handling certifications offered by the state department of agriculture for workers and suppliers.

He also noted two other factors that play into the local produce trend: “Some of this is being driven, literally, by transportation costs.” Less expensive logistics are important to businesses with razor-thin margins.

At the other end, more customer loyalty programs make it easier to track purchases, which greatly aids in recalls or at least tracing and isolating problems.

“That is a very important development,” said Pegg, “and a critical piece of the supply chain.”