Black Swan

Lost In The Haze

In the summer of 1783, Europeans wondered about a sulfurous haze stagnating over the continent. Today, thanks to CNN and Twitter, we would immediately know the source: a volcanic fissure in Iceland. It was the country’s last major fissure eruption.

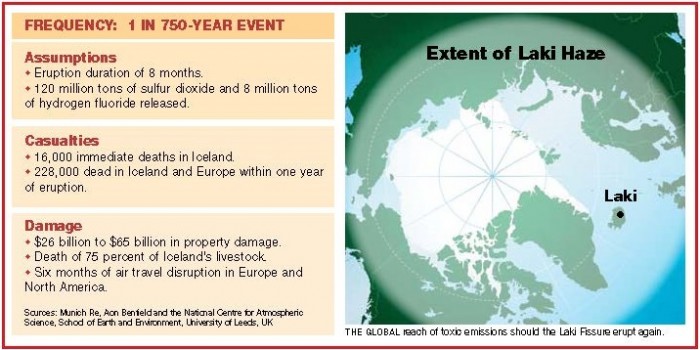

That eruption killed roughly a quarter of the people then living in the country, decimated crops and livestock, and darkened the skies in Europe and beyond. If a similar event were to occur in modern times, the damage would be immense.

“The sun, at noon, looked as black as a clouded moon, and shed a rust-coloured ferruginous light on the ground and floors of rooms, but was particularly lurid and blood-coloured at rising and setting,” wrote the English naturalist Gilbert White, a contemporary witness.

White had a rare opportunity. Fissures such as Laki erupt roughly every 300 to 1,000 years, according to geologists Thorvaldur Thordarson and Stephen Self, who wrote a review of Laki’s global impact. About half a dozen fissure eruptions are believed to have taken place in the last 1,200 years, with the largest occurring in Iceland. Scientists believe it is only a matter of time before another one occurs.

Low-Lying Dangers

A fissure eruption differs from an explosive eruption in several ways. The latter hurl gas and ash high into the atmosphere, and they tend to subside relatively quickly, wrote Thordarson and Self. Fissure eruptions typically last longer, months or even years, and their emissions affect lower levels of the atmosphere, impacting air quality and yielding more dramatic effects.

A Laki-style event today, even with a healthier population and improved medical care, could cause hundreds of thousands of deaths from exposure to increased air pollution in Europe alone, according to an analysis by Anja Schmidt, a researcher at the University of Leeds in England.

“Such a volcanic eruption would therefore be a severe health hazard, increasing excess mortality in Europe on a scale that likely exceeds excess mortality due to seasonal influenza,” Schmidt and her co-authors wrote in a 2011 article. The main culprit, they said, would be fine particulate matter.

The deepest impact of the Eyjafjallajökul eruption of 2010 was on travel. The volcano’s ash plume shut down air traffic between Europe and North America for six days. In addition to stranding travelers, the suspension hurt companies dependent on planes to deliver parts and supplies.

Overall, the economic impact of Eyjafjallajökul has been estimated at between $2.6 billion and $6.5 billion, said Anselm Smolka, head of corporate underwriting and geological risk research for Munich Re.

A large fissure eruption could easily cause 10 times the damage, he said. “There’s no doubt it would be economic losses going into the tens of billions.”

Airplanes might be grounded for months, Smolka said. Ocean transport also could be disrupted. Shippers, concerned about fine ash damaging engines, might seek new routes, which could take longer.

Crops would suffer, Smolka said, though the extent of the potential damage is unclear. Some argue that modern crops are more robust, he said. Others point out that there is less variety today, so if crops fail, the losses would be more widespread.

“No doubt there would be consequences,” Smolka said. “How serious they are and what areas are affected, I think there’s clearly need for further research to be done.”

A Creeping Chill

The Laki eruption, involving a series of fissures extending more than 10 miles, began in June 1783 and lasted for eight months. As haze drifted over Northern and Western Europe, it lowered temperatures and led to thousands of premature deaths.

Some scholars argue that the resulting poor harvest in France helped spark the French Revolution six years later.

The haze eventually spread around the northern hemisphere, drawing the attention of Benjamin Franklin, who noted a dry fog and colder temperatures settling over much of North America. In February 1784, ice fragments bobbed in the Mississippi River as far south as New Orleans, according to Thordarson and Self. A drop in rainfall over northern Africa and India also has been attributed to the Laki eruption.

A similar event today would set off a humanitarian crisis in Iceland, while those outside the country would be worried about potential effects on health and travel.

“Here, you have a problem with no known solution,” said Nancy Green, an executive vice president with Aon Risk Solutions and an expert in Black Swan events. “Don’t underestimate the fear factor associated with that.”

Air traffic would likely cease for months. The ash and haze would do more than damage jet engines. Sulfur dioxide levels in the atmosphere could be potentially toxic to air passengers, according to the National Risk Registry of Civil Emergencies, an annual list of potential threats compiled by the UK government.

The initial advice from governments in countries downwind of the eruption would be practical, said John Rendeiro, vice president for global security and intelligence at International SOS, an international travel security and medical assistance company.

“Public health services would probably be recommending that people stay indoors, keep their windows closed, wear masks,” said Rendeiro.

After the warnings, people and companies would likely seek more detailed advice about what to do, much as they did in the wake of the earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011, Rendeiro said. “A lot of people worried.”

Insurers would first see claims for property damage in Iceland. Outside the island country, however, it’s unclear how or even whether insurance policies would respond.

The biggest losses would likely be in the area of business interruption, said Duncan Ellis, U.S. Property practice leader for Marsh. But unless companies can trace the interruption to physical damage at their own facilities or at the facility of a supplier, insurance would not kick in.

Companies that carry supply chain insurance, which does not rely on physical damage as a trigger, would fare better, Ellis said. But such policies are not widely held.

“It really hasn’t caught on to the degree that we thought it would, despite having had a number of such interruptions over the last few years,” Ellis said.

Airlines expressed interest in better coverage following the 2010 volcano, as few, if any, were covered for their losses then, said Munich Re’s Smolka. “But the market developed, I would say, very, very slowly.”

The Property Toll

While many businesses might have to eat their losses, individuals might stand a better chance of compensation.

After Eyjafjallajökul, people who had to cancel travel plans collected on insurance policies offered by their credit card companies, said Matt Carrier, a principal at Deloitte Consulting who leads the firm’s national Property and Casualty Actuarial practice. Some card issuers absorbed the costs; others had insurance.

“It wasn’t like it was going to put them out of business,” Carrier said. “But there were significant losses.”

A longer-lasting eruption could ratchet up those losses, Carrier said.

Of greater concern, especially in the United Kingdom and Northern Europe, would be potential claims by homeowners whose houses might, in theory, be damaged by ash, smoke or haze in some way. Homeowners have pressed successful claims for smoke damage after wildfires, Carrier said. If similar claims came in from across wide swaths of Europe, he said, it would threaten the viability of some insurers.

“If you’re talking about ash that could cover a significant portion of the United Kingdom and Europe, and literally every home you have is triggering a $2,000 or $3,000 event, that could definitely put companies out,” he said.

Businesses could claim similar damage, especially if the ash and haze kept coming for months, Carrier said. The claims could spur disputes over policy language and the links between specific damage and the volcanic event.

“I would actually envision potentially a lot of money spent by companies, and maybe even insurance companies, building out models to prove or disprove that this event has caused acid rain, which has caused a reduction in crop production linked back to our coverage,” he said.

Other fights might arise over whether the eruption was a single event or multiple events.

“We get involved in contentious discussion in the industry about whether a storm is a storm, and that’s for an event that happens far more frequently than something volcanic,” said Neil Harrison, a group managing director at Aon Risk Solutions.

“So there’s going to be all kinds of debates about what is covered.”