Energy

LNG Exports Challenge Capacity

In a change that is the stuff of fantasy for anyone who remembers the energy crises of the 1970s, the United States and Canada are on the verge of becoming significant global energy exporting countries.

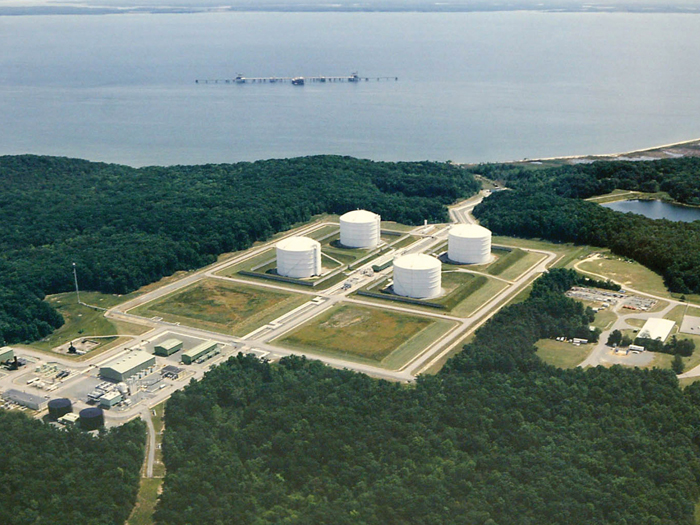

On the leading edge of that change are massive terminals for exporting liquefied natural gas (LNG), each facility costing as much as $30 billion. Several are being built and many others are planned. A few of the LNG import terminals around the country that are already in operation are being converted to export operations, at the bargain price of about $10 billion.

Underwriters, reinsurers and brokers said that the size and cost of the projects present challenges to capacity from several angles: the exposures inherent in any one project, the fact that many are taking place at the same time and the reality that the natural-gas bonanza is also driving other major capital investments, such as petrochemical plants, which are in effect competing for coverage.

“All the major brokers and the boutique energy shops are already active,” said one senior insurance executive, “but for these big projects, it almost doesn’t matter who the retail broker is in the United States because the business is all being driven in London.”

The coverage is not just standard builder’s risk and property/casualty for a massive construction project, it is also for highly specialized equipment to deal with ultra-low temperatures. At an export facility, natural gas is cooled to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, and the LNG is loaded onto tankers that are essentially huge floating insulated bottles.

And just for added excitement, most of the projects are being constructed or planned on the U.S. Gulf Coast or East Coast. As a result, named windstorm capacity is challenged as well.

“The physical risks and the cryogenic process itself drives the capacity requirement for these facilities,” said Louis Gritzo, vice president of research for FM Global. Before joining that underwriter, he was with Sandia National Laboratories and led the government task group examining LNG proposals and operations.

The Sudden Production Boom

The United States has dabbled in LNG for many years. A lone export terminal in Kenai, Alaska, has been operating since 1962, shipping gas from the Cook Inlet to Asia. Separately, a handful of import terminals were built in the late 1990s, when the widespread belief was that the country was running out of natural gas. All that changed when domestic independent oil and gas companies brought together three-dimensional seismic surveys, directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing. That allowed hydrocarbons to be extracted from source rock, usually shale, and the bonanza was on.

According to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, there are more than 110 LNG facilities operating in the country today, performing a variety of services. Some facilities export natural gas from the United States, some provide natural gas to the interstate pipeline system or local distribution companies, while others are used to store natural gas for periods of peak demand. There are also facilities that produce LNG for vehicle fuel or for industrial use. Depending on location and use, an LNG facility may be regulated by several federal agencies and by state utility regulators.

In the early heady days of the unconventional gas rush, thousands of wells were drilled. As a result, overproduction pushed the price of natural gas from a peak near $13 per million Btu (mmBtu) in June 2008, to below $2 per mmBtu briefly in April 2012. Those prices are quoted at the Henry Hub pipeline center in Oklahoma. Another common reference price is the Nymex spot contract, quoted in thousands of cubic feet, but the two numbers are equivalent because U.S. and Canadian pipeline rules specify pipeline gas to be almost pure “lean” methane; 1,000 cubic feet of gas provides 1 million Btu of energy.

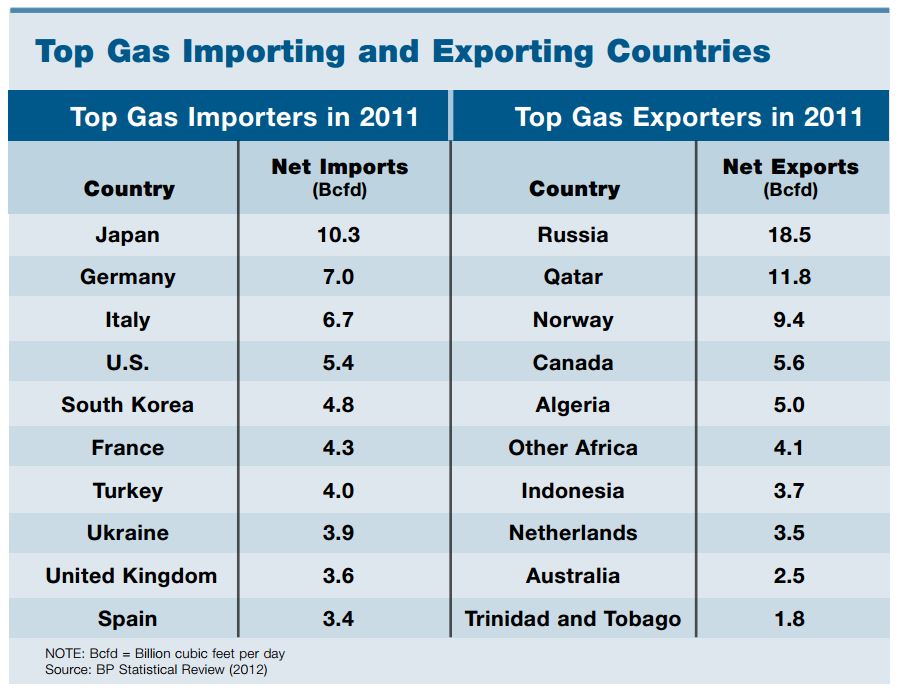

For most of 2013, the price has kept in the range of $3 to $4 per mmBtu, while the price of LNG landed at Tokyo is about $16 per thousand cubic feet. That creates an irresistible arbitrage that makes LNG a profitable proposition even at $30 billion for an export terminal.

According to the April 2013 Willis Energy Market Review, the insurance market remains highly competitive, even in light of the challenge to capacity, because of the “diversity of construction risks and relatively low loss ratio compared to other classes.”

“LNG projects continue to constitute the largest element of the onshore energy construction projects requiring cover from the international construction market, most notably from the United States and Australia, where significant development continues unabated,” according to the report.

Since a low point following the hurricanes of 2005, official capacities now total in excess of $5 billion for the first time, Willis reported. When the broker first started compiling the data 20 years ago, the market offered a mere $1.6 billion of capacity to its clients. Willis cautioned, however, that “these stated capacity figures are based on the maximum figure that an insurer is theoretically able to commit to, bearing in mind reinsurance and management restraints; they do not reflect what can realistically be obtained in the market, even for the most attractive business.”

The report explained that “because there have been few new entrants to the market this year — with the exception of the Apollo Syndicate and Ironshore, which have recently recruited Simon Mason and Paul Calnan respectively, both highly experienced upstream underwriters — and because the number of insurers involved in upstream business predominantly remains essentially the same as last year, we have calculated that the maximum that buyers can reasonably expect to purchase in this market has only increased modestly since last year, from circa $4 billion to $4.2 billion.”

As a result, Willis stated, “the market focus for large-scale LNG projects is now very much on London and European carriers, which are able to provide significant capacity on a probable-maximum-loss basis rather than a total insured value basis.” However, the report noted, with significant contract values normally in excess of $5 billion, the potential losses due to material damage means there remains a shortfall of available capacity globally for any resulting delay in start-up risk.

“You just need a certain size to be cost-effective,” Gritzo said. “Not just refrigeration, compression and storage, but sensors and controls, all of special steel and other materials. When metals get cold they react very differently.” Beyond the normal perils of a massive construction project in a hurricane zone, leaks and fire are hazards. “Because of the nature of LNG, big explosions are actually not a major risk-management driver,” Gritzo added, “but spills and fire hazards are real, and they definitely figure into siting considerations.”

“You just need a certain size to be cost-effective,” Gritzo said. “Not just refrigeration, compression and storage, but sensors and controls, all of special steel and other materials. When metals get cold they react very differently.” Beyond the normal perils of a massive construction project in a hurricane zone, leaks and fire are hazards. “Because of the nature of LNG, big explosions are actually not a major risk-management driver,” Gritzo added, “but spills and fire hazards are real, and they definitely figure into siting considerations.”

Capacity is Pinched

Several U.S. and Canadian underwriters said they are only just exploring the LNG business, but some carriers have experience in the sector internationally, especially in Australia, a major exporter already and growing bigger. Allianz is involved with several LNG export operations, as well as others planned. One is a floating platform, “like building a refinery on a boat,” said Carlos Carillo, head of energy for the Americas at Allianz.

He ticked off the many elements of coverage necessary, the builder’s risks, P&C and marine, including Project Cargo. “Large, heavy and expensive components for these plants are built in the Philippines or Indonesia, and brought to the site in special vessels.” That protection is augmented by coverage for delay in start-up if a component was damaged or defective.

“The brokers find a lead market for each project,” Carillo said, “and then put out terms to find other markets, either layered in a fixed ratio or non-proportional. There are a lot of negotiations, and for financed projects, the lenders have a lot to say about how much the owner will have to place.

“The global demand is there for LNG, and the financing is available. The challenge is capacity. There are some options for non-traditional risk transfer, including what’s offered via the Allianz Risk Transfer unit, but that is something that we will have to watch.”

Andrew Seeley, underwriting manager for energy for Allianz in Australia, added that “capacity also depends a lot on the project sponsor. Many but not all of the global majors and national oil companies tend to self-insure. They don’t really buy cover; that goes to their captive.”

For the exposures they do transfer, he said, “the owners like to buy on the global market. We have a fair amount of capacity down here, but they would have to find more globally.”

Looking ahead, Seeley said, “North America and East Africa are the next LNG export hot spots. Demand for LNG is set to double in the next 10 years, and by 2020, Australia is expected to overtake Qatar as the top exporter. There are currently seven plants under construction down here, at about $27.3 billion [U.S.] each.”

David Fox, area senior vice president for A. J. Gallagher, said the “projects are huge, but it’s not just because there is a lot of steel and concrete and many workers. Several of these plants are being built on the Gulf Coast, and the various insurance markets are just not deep enough.”

There are also variables outside the project, especially regulatory and financial uncertainties, Fox said. “Energy policy in the U.S. is not clear, and there are costs and complications in that. Also, some of the projects are in master limited partnerships, or other specialized financial structures. Those tend to need more belt and suspenders coverage to make them acceptable to investors. So commercial contracts have to be structured to close the gap in insurance.”

There are important second and third dimensions to the capacity challenge, said Chaman Aggarwal, national energy construction practice leader for Marsh. “This market does not have $20 billion capacity for natural catastrophe coverage on the Gulf Coast [the price of one terminal] and there are several projects under way or planned. Also, there are other huge capital projects — fertilizers, petrochemicals, methanol, fuels — all downstream from this shale gas boom, and all of them competing for capacity.”

Aggarwal suggested that beyond traditional insurance markets, “the capital markets have been fairly eager to provide some capacity, often in the form of Cat bonds or insurance-linked securities. There is also some self insurance, but most owners do not do that straight. The major oil companies will take large retentions, but they do go to the market.”

His position is proof of that. “I was hired to focus on new business,” said Aggarwal. “As these projects come about, the challenge for the owners will be to find solutions, not just capacity. We just completed a placement of Cat bonds for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in New York to protect them from storm surge. That is not LNG, but they are a multi-billion-dollar investment in a coastal region. The big issue for them or for an LNG terminal is the sheer magnitude of the value to be protected, and the complexity of the operation.”

For all the challenges presented to the insurance market by this gas bonanza, the underlying business case seems to be sound. According to a recent Deloitte analysis, Exporting the American Renaissance: Global Impacts of LNG Exports From the United States, the highest natural gas prices are currently in Asia where major LNG importers, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, pay a premium to ensure peak month deliverability.

The report stated “prices for spot LNG cargos sometimes shoot up in the winter months primarily because these Asian countries, with almost no other natural-gas alternatives, vie against each other for the scarce available LNG cargos and bid up prices. For much of 2012, the landed price of LNG in Japan hovered around $15 per mmBtu, or about five times higher than Henry Hub prices in the United States. With growth in global LNG supplies, the highest priced markets will not be setting the price, since their demand will be the first to be satisfied and other, lower price markets will likely provide the marginal demand and set the price. Hence, the world gas model projects a sharp decline in Japan prices coinciding with growth in Australian LNG exports.”

Vocal Opponents Remain

It should be noted that several industrial interests in the United States have been vociferous in their opposition to LNG exports, notably the chemical industry, and Dow Chemical in particular. They believe that exports will raise domestic gas prices and stifle the nascent U.S. industrial renaissance that is based on gas being cheap and plentiful. Similar concerns have been voiced in Congress.

Domestic oil and gas companies dispute those fears. At the recent summer meeting of the Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners Association in San Antonio, senior executives at several major gas producers noted that after several years of rock-bottom prices, a significant portion of gas wells are shut in. They stressed that it would take more than just one or two LNG terminals to “move the needle” on gas prices, and added that if prices were to rise significantly, fields that are currently uneconomical would be brought back online and drilling accelerated.

In short, gas producers say if you build it, the molecules will come.