Employment Practices

Flavored With Danger

Manufacturers of foods and consumer goods must pay attention to the serious — and sometimes fatal — health risks associated with employee exposure to a growing class of chemical compounds used to enhance scents and flavorings.

For example, workers in flavoring or food production who inhale diacetyl or its substitute, 2,3-pentanedione — common components of butter, nut, and other flavorings — risk a rare lung disease called obliterative bronchiolitis, said Dr. Kathleen Kreiss, field studies branch chief for the division of respiratory disease studies at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in Morgantown, W.Va.

Obliterative bronchiolitis is irreversible and the principal symptoms are cough and shortness of breath, which limits exertion, Kreiss said. The disease is seen in workers making microwave popcorn and cookie dough with artificial butter flavoring, as well as other flavorings.

The disease also strikes workers in coffee processing plants who are exposed to the chemicals from the roasting and grinding of unflavored coffee, as well as the flavoring of coffee with nuts and other types of additives.

“It is hard to diagnose because breathing tests and X-rays can be normal even when affected workers have chest symptoms, and sometimes a biopsy is required to make the diagnosis,” Kreiss said.

“The disease can come on with only months of employment and can progress very rapidly to severe impairment.”

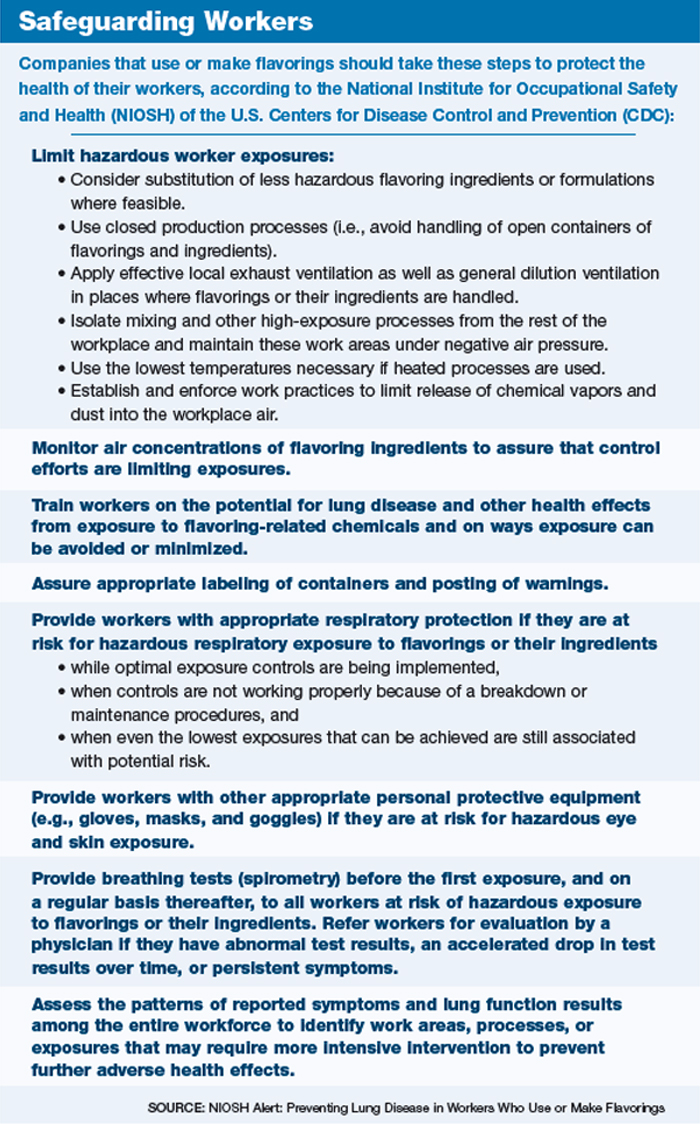

Manufacturers should limit worker exposures to artificial flavors containing diacetyl and related chemicals by providing additional respiratory protection until engineering controls are implemented, such as exhaust ventilation of potential sources of exposure, she said.

“The disease can come on with only months of employment and can progress very rapidly to severe impairment.” — Kathleen Kreiss, field studies branch chief for the division of respiratory disease studies at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Moreover, to ensure that affected workers are identified early — before they have severe lung problems — manufacturers should institute medical surveillance to check for chest symptoms and conduct spirometry tests to assess conditions that affect breathing, Kreiss said. Medical practitioners should also evaluate if spirometry measurements are falling excessively over time, even in workers who still do not exhibit symptoms or breathing problems.

Workers have successfully sued their employers for failing to adequately protect them against such exposures. In 2004, Eric Peoples and more than 30 of his co-workers at a Jasper, Mo., popcorn plant won a $20 million verdict against International Flavors and Fragrances for severe lung injuries, and other workers at that plant obtained additional verdicts totaling $17.7 million.

Ace Group’s ESIS Health, Safety and Environmental Services in Chicago advises its manufacturing clients to first consider substituting a less hazardous ingredient with a safer alternative, said David Duffy, a certified industrial hygienist and principal consultant for ESIS.

“That’s a very powerful way to solve the problem but it’s easier said than done to find something that tastes similar to what the manufacturer has tried to achieve,” Duffy said. “It has been done, so if a company can do this, it’s a very strong and positive way to protect workers.”

If a substitution is not possible, manufacturers should then consider alternate work assignments for workers who are particularly sensitive to certain chemical compounds, he said. They should also limit exposure by engineering closed production processes that minimize employees’ exposure to potentially dangerous chemical compounds. However, this can be challenging for plants with older equipment, particularly those facilities that still rely on a lot of manual operations.

“In those cases, companies should consider engineering to reduce exposure,” Duffy said. “They need to use a team approach to figure out ways to adjust the process — they can ventilate the area, automate the process or incorporate new engineering concepts and design and retrofit the equipment.”

Alternatively, many manufacturers are implementing new processes that have been designed with the engineering controls in place, “which is a huge benefit,” he said.

Manufacturers should also implement work practices and training programs to ensure safe handling and storage of these compounds, particularly since the sophisticated equipment in manufacturing today takes trained personnel to operate, Duffy said. However, one of the main challenges has been making sure older employees who have been used to working with safer chemicals adapt to the different practices required for handling riskier chemicals.

“It’s very hard to change those behaviors and mentality by incorporating safety concepts,” he said.

“It can be done, but when a company has new processes or chemicals, oftentimes it’s tough for some older employees to modify what they have been doing for years. They don’t understand that handling chemicals today should be different than how they handled chemicals years ago.”

For some organizations, combining engineering such as exhaust systems with employee training and education “can go a long way,” Duffy said.

“The problems we are finding … have to do in a lot of cases with some of the new chemicals being put into the stream of commerce and through the manufacturing process,” Duffy said.

“It’s very difficult to assess risks associated with new chemicals that don’t have established exposure limits or ways for us to monitor airborne levels or employee exposures. So we are back to dealing with unknowns — which makes these steps and other safety and health measures even more important.”

JoAnn Sullivan, a San Jose, Calif.-based senior vice president and managing consultant at Marsh Risk Consulting’s workforce strategies practice, said that manufacturers should be used to managing exposures to chemicals that have been shown to be risky at concentrated levels during manufacturing, as issues related to food additives and chemically altered products were first identified in the 1960s.

There was quite a lot of press on certain food colorings in soft drink mixes and other products, which led to changes in how these products were manufactured for consumption, Sullivan said.

“Risk managers have a very strong commitment to adhering to OSHA regulations and best practices to prevent exposures to employees in manufacturing processes that handle highly concentrated products,” Sullivan said.

“Employees could get exposed if they ingest the chemical in any way, including if it gets on their hands and then they eat a sandwich, if they breathe it or it gets into any of their mucous membranes or even their ears.”

The chemicals that make up the additives are required to be identified on safety data sheets that are used in the plants, so employees can review and understand the potential exposures to the chemicals they are working with, she said.

“It’s very difficult to assess risks associated with new chemicals that don’t have established exposure limits or ways for us to monitor airborne levels or employee exposures.” — David Duffy, a certified industrial hygienist and principal consultant for ESIS.

Third-party administration companies handling workers’ compensation programs for manufacturers are looking for controls in the work environment, which could include engineering fume hoods, negative-pressure workrooms in which hazardous vapors are constantly being removed, or rooms that constantly draw chemical residue away from the work area, Sullivan said. Employees might also wear full-body Tyvek suits, or “bunny suits” if they are working in areas where there are high concentrations of certain chemicals.

Marsh also recommends that manufacturing clients have medical surveillance programs for their employees, based on the type of toxins or exposure, she said.

“Such programs may tests employees’ lung function, blood or urine on a periodic basis, and they let them know that they will do this when they hire them,” Sullivan said.

For some additives, the European Union’s safety standards currently list stricter controls, testing procedures and requirements than the United States, so multinational companies operating there need to make sure they comply with those rules, she said.

As for Marsh’s manufacturing clients, Sullivan believes they have demonstrated that they have taken these risks seriously by putting into place very strong industrial hygiene programs, good quality control methodology and the right people to oversee safety programs.

“They don’t want to have workers’ compensation or product liability claims and bad press,” she said. “Most are doing a bang-up job, but that said, there are new technologies all the time such as nanotechnologies to distribute chemicals, and the jury is still out about the impacts. Companies, watchdog groups and the government are continually monitoring those new technologies.”

From a consumption standpoint, watchdog groups are looking for complete and truthful labeling on products, as it is not enough that chemical additives, which enhance flavors or increase the longevity or stability of a product, are included on the ingredient listing on the packaging, Sullivan said.

“Companies might put down certain additives followed by several others, but they don’t indicate that they’ve been mixed together, or they don’t list the quantity of a certain item,” she said.