Supply Chain Risk

Farm-to-Table’s Food Safety Perils

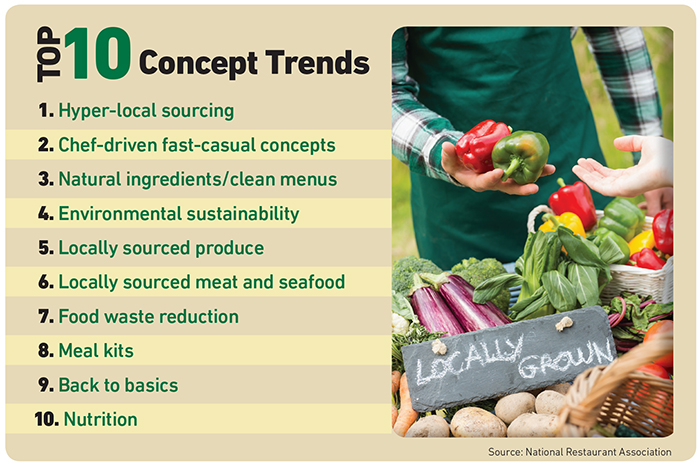

The National Restaurant Association surveyed 1,298 members of the American Culinary Federation in October 2016, asking them to rate 169 items as a “hot trend,” “yesterday’s news,” or a “perennial favorite.”

The chefs and restaurateurs ranked ‘hyper-local sourcing’ as the No. 1 concept trend. Eighty percent of respondents called this a “hot trend.” Locally-sourced produce was ranked number five, and locally-sourced meat and seafood was ranked number six.

A variety of factors are driving the farm-to-table trend, which focuses on sourcing products from suppliers located within 100 miles from the restaurant. Environmental sustainability is one of those factors.

As the effects of climate change become more evident and more widely publicized, consumers seek ways to reduce their carbon footprint. Trucking in food from an hour away versus from across the country significantly reduces the emissions generated from food transport.

An increased focus on health and wellness is another factor. More and more, diners not only want to consume fresh food, they also want to know just how fresh it is. Knowing that your salad is made of veggies harvested from an organic farm just 50 miles away makes that food seem more wholesome.

Finally, a desire to support small farmers and local businesses is another reason restaurant patrons want farm-to-table menus.

Food Safety Risks

Conventional wisdom suggests that eatery owners should be all for this trend, as shorter supply chains typically equal less risk.

Restaurateurs can go out and visit their supplier themselves, talk to the farmers in person and see their processes with their own two eyes — and be back at their businesses within a few hours. Delivery time is shortened. There are fewer middlemen.

But removing those intermediaries makes it harder to control food safety. Smaller suppliers might not be subject to the same regulatory oversight that a big producer would be, and they lack the resources of large commercial farms and food processors to do thorough and regular ingredient testing. Cutting out intermediaries could also mean reducing the number of quality control checkpoints.

If a farm-to-table restaurant has locations in multiple regions, the supply chain also grows fragmented since each location will use a different network of local suppliers. That makes it even harder to control food quality and ensure product consistency.

“Quick-serve restaurant chains have the special challenge of needing to be responsive to consumers’ growing interest in farm to table, but the volume of standard ingredients they require for national distribution exceed the capabilities of almost all local producers,” said John Quelch, food safety expert and Dean of the Miami Business School.

“They therefore have to work with and qualify many local producers to meet their quality control and food safety standards, which inevitably adds cost.”

It also adds liability.

Large commercial farms and food manufacturers are subject to more regulatory scrutiny and inspected far more frequently.

They are more likely to have established safety and food testing procedures and on-site inspectors. Small, local farmers are typically less experienced in food safety testing or USDA inspections.

“Dealing directly with small, individual farms means taking on a lot of the quality control responsibility yourself.” — Scott Aiello, vice president, product manager, industry practices, Liberty Mutual

“Large farms and manufacturers that are selling into Giant or Wegmans are going to be forced to meet certain standards. It’s harder to ascertain whether smaller operations are adhering to recognized standards,” said Martin Bucknavage, senior food safety extension associate, Penn State Department of Food Science.

“When you’re dealing with a food wholesaler, you can be fairly certain given their size and focus on the industry that they have the right controls in place and are dealing with reputable farms,” said Scott Aiello, vice president, product manager, industry practices, Liberty Mutual. “Dealing directly with small, individual farms means taking on a lot of the quality control responsibility yourself.”

Outbreak Aftermath

A foodborne illness outbreak can cause potentially irreparable reputational damage to a restaurant, on top of bodily harm to patrons.

“We’ve seen some restaurants in the past completely go out of business due to foodborne illness. Even massive chains have struggled with it,” Aiello said.

Chipotle offers the most recent and high-profile example. The fast-casual Mexican chain touts its commitment to sourcing from local farms, not factories. Its website says it “served more than 30 million pounds of produce sourced from local farmers around the country in 2015.”

A recent norovirus outbreak was linked to Chipotle in July 2017, on the heels of previous norovirus, E. coli and salmonella outbreaks in 2015, sending their shares tumbling 13 percent. It also sparked a class-action lawsuit filed by shareholders, claiming the chain has misled them about its efforts to resolve its cleanliness and food safety issues.

Widespread illnesses can also lead to lawsuits from consumers seeking damages for their medical care, lost income, and pain and suffering.

Despite the risks, the farm-to-table movement shows no signs of stalling. And restaurant owners can serve locally sourced food safely as long as they do their due diligence.

“Have approved suppliers. Don’t just go down to the local farmers’ market and buy from whomever. Know who you’re buying from,” Bucknavage said. “You have to see for yourself that the farm is a legitimate business with quality and safety standards in place.”

Restaurateurs can start by checking a farm’s audit history. The USDA as well as other third parties provide farm inspections. Regular audits indicate that the farmer is trying to comply with federal food safety standards.

But it also requires a boots-on-the-ground approach.

“Pay attention to the layout of the farm — are animals being kept away from produce? Many outbreaks are linked to contamination of fresh fruits and veggies with animal waste. Are workers washing hands and keeping their equipment clean? How many times are the food products washed before delivery? What temperature control protocols are in place both on the farm at the time products are harvested and processed and while they are in transport?” Aiello said.

The farmer should have records to indicate when produce was picked and where, and how long it was stored, as well as what temperature it was stored under. He should also be able to detail how he applies fertilizers or pesticides, and how the irrigation system works.

“If you ask the farmer if he follows good agricultural practices, and he looks at you like you have two heads, that’s not a good sign,” Bucknavage said.

Farmers should also have controls to prevent the cross-contamination of allergens and proper labeling of allergens on any packaged products. Serving food that is not properly labeled for allergens can have negative effects similar to foodborne illness.

These tasks would ordinarily fall to a distributor when working with a larger supplier. Going farm-to-table requires restaurant owners and managers to take on these tasks themselves. They might not be able to inspect every farm every day, but they can instill food safety practices in the kitchen to guard against errors on the farmer’s part.

“You can check the temperature of the delivery truck and of the product. You will need to wash all the produce before use. You can make sure every employee is washing their hands,” Bucknavage said.

Some quality control tasks should also be transferred back to the farmer, however, through precise contractual language.

“Contractual risk transfer is a cornerstone of risk management. It shouldn’t be viewed as less important just because you’re dealing with a small, family-run farm. A handshake won’t do it. Clear contracts hold people accountable,” said Aiello.

The contract can establish what a restaurant’s expectations are around the farmer’s food safety practices and stipulate what insurance he must maintain.

“That will mean there’s an extra layer of due diligence being done by the farmer’s underwriter as well,” Aiello said.

Insurance and Crisis Management

Should the worst happen, restaurant owners should have a crisis management plan at the ready, including expert resources on tap who can handle the PR and communications strategy in the event of an outbreak.

“Legal expertise can help you understand exactly what the allegations are against your restaurant if someone files a lawsuit, and whether the responsibility should be placed on your suppliers, and how to hold them accountable,” Aiello said.

Insurers with industry expertise can usually help to build these crisis management networks and tighten up contract language. General liability coverage as part of a business owner’s policy may pick up financial losses from litigation. Crisis management coverage may also be included in the BOP or available as an endorsement. &