The Connection Between Climate Change and Credit Risk: A Deeper Look at the Cost of Severe Weather Events

Heat waves have killed tens of thousands of people in the past decade.

Climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme and costly weather events such as storms, hurricanes, extreme rains and heat waves. These are increasing costs and risks to cities, in turn threatening their credit rating and their cost of borrowing money.

To date, the potential impact of adopting smart surface strategies on city credit rating has been largely overlooked. Our analysis demonstrates that cities that choose to not adopt smart surfaces will experience significantly increased climate related losses, increased risk of credit rating reductions and associated increases in city borrowing costs.

Over time, these combined threats will increase risk of insolvency for cites that do not adopt resilience strategies such as smart surfaces. This work is part of the Smart Surfaces Coalition, comprised of 30 partners, including the National League of Cities and the American Institute of Architects.

This three-part series provides rigorous description and quantification of the costs and benefits of city climate change mitigation strategies on their credit risk. In Part One, the authors explored the background of smart surfaces and their impact on a city’s credit and risk management.

In this section, Part Two, the authors aim to dive deeper into the impact increased severe weather events have on a city, looking at heat waves and flooding as prime examples.

Part Three concludes the authors’ research, highlighting several benefits to having a smart surface strategy in place to increase climate change resiliency and decrease costs for a city.

City Debt Burden/Exposure

There is a large range of city indebtedness, although the overall level of city indebtedness is generally rising. For example, Cincinnati owes nearly $1.25 billion, triple what it was 25 years ago when adjusted for inflation.

City debt represents a large portion of spending for many U.S. cities.

An extreme example is Milwaukee, where debt service alone took up 34% of fiscal 2015 governmental fund spending, according to the city’s comprehensive annual financial report. A recent analysis of fiscal year 2016 expenditures in cities with populations over 500,000 found that “the largest legacy line item for many localities is debt.”

The U.S. urban population estimate as of 2016 is 265 million.

The total amount of outstanding municipal debt at year end 2015 was $1.8 trillion and rising, so the per citizen city indebtedness is $6,792, conservatively assumed as $6,800 for current calculation purposes.

In 2015, $218 billion of new debt was issued or $822 per person. In 2015, local governments spent $75 billion on debt interest or $283 per urban dweller each year.

Credit Rating and Interest Rate

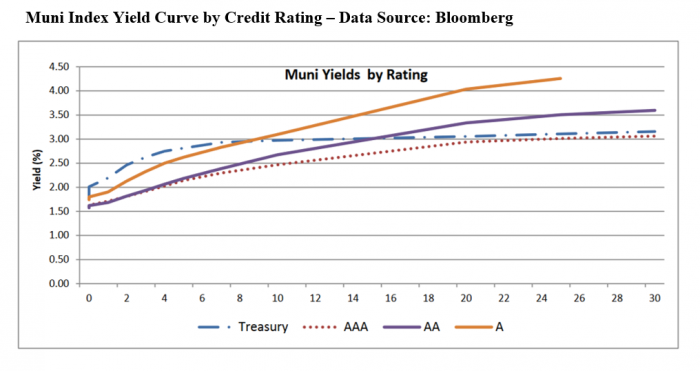

Various studies show a strong correlation between credit rating and interest rate.

Research shows that lower credit ratings have higher associated yield across the range of bond terms from 1 to 30 years. The difference in interest rate between rating grades, for bonds rated AA and lower, are now approximately 40 basis points (0.40%) as of spring 2018. That is, each reduction in rating level is associated with an increase in interest rate of 0.4 %.

The difference in interest rate between rating grades, for bonds rated AA and lower, are now approximately 40 basis points (0.40%) as of spring 2018. That is, each reduction in rating level is associated with an increase in interest rate of 0.4 %.

This analysis assumes that each bond rating reduction is associated with a slightly lower increase of 0.35% in interest rate per reduction in rating. (Assuming 0.35% is conservative because it is a somewhat lower benefit from avoiding a credit rating reduction.)

The exception to this is the single step rating reduction between investment grade and junk grade.

Bonds are generally classed as either “investment grade” or not, based on their credit rating, with some using the term “junk bond” for bonds below investment grade.

The term “junk bond” is a pejorative term and reflects an industry-wide historic view that bonds issued by organizations with credit ratings below BBB, are considerably riskier than investment grade bonds.

As noted above, the interest rate impact of a single credit rating decrease is around 0.35 (e.g. 35 basis points increase in cost of borrowing). However, a one credit rating decrease from investment grade (BBB-) to a junk bond (BB+) is larger, due to the psychological impact of investing in a bond classified as “junk” or “non-investment grade.”

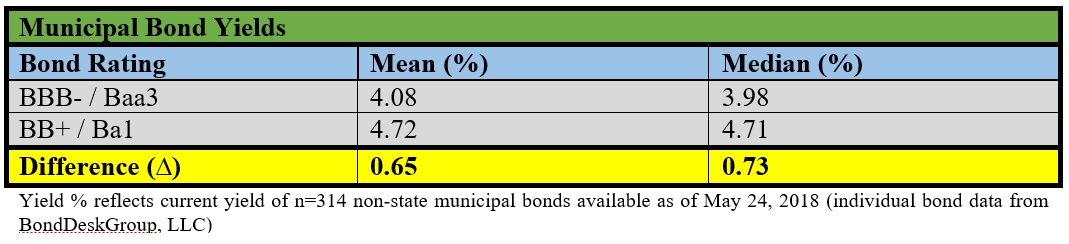

In order to determine the average interest cost increase for a reduction in bond rating, we undertook a quantitative analysis of available bond data.

To do so, we looked at every non-state, non-zero-coupon, municipal bond available through BondDeskGroup and with a credit rating of either BBB- (S&P, Fitch) or Baa3 (Moody’s) and BB+ or Ba1 (as of 5/24/2018).

We omitted all bonds that either did not have sufficient data or where the data was distinctly separate from the rest of the data. The yields for all BBB- or Baa3 were then averaged and the median was found. The same method was used for all BB+ of Ba1 bonds to find the numbers summarized in the following chart: Our analysis of over 300 municipal bonds available for purchase as of May 24, 2018 showed that the average yield for BBB- or Baa3 bonds is 4.08%, whereas BB+ or Ba1 bonds have an average yield of 4.72%.

Our analysis of over 300 municipal bonds available for purchase as of May 24, 2018 showed that the average yield for BBB- or Baa3 bonds is 4.08%, whereas BB+ or Ba1 bonds have an average yield of 4.72%.

This equates to an average increase of 0.65% and a median increase of 0.73% (65 basis points (BP) and 73BP, respectively).

This study assumes a cost of borrowing increase of 0.65% when city bonds drop one rating level from investment grade to junk status.

For a city like Cincinnati, as an example, with $1.25 billion dollars in debt, the effect of a single step credit rating decrease into ‘junk bond’ territory could cost the city over $8 million dollars annually.

A city of 100,000 with $900 million dollars of debt that experienced a one-step downgrade in credit rating would, as those bonds get issued, experience an increased borrowing cost of $2 million per year or $40 million over the life of a 20-year bond.

This translates into an extra $300 in interest per person.

If Moody’s or S&P reduces its credit rating by three levels, it would increase the interest rate by 1.2% and increase the interest cost per person over the 40-year period by $1,224. Each billion dollars borrowed would increase costs on interest by $5.1 million dollars per year or $204 million over 40 years.

Higher interest costs increase a cities risk of not being able to repay, thus increasing the risk of default and in turn increasing the likelihood of further cuts in credit rating.

Smart Surfaces and Risk Mitigation

Cities are faced with the prospect of rating agency credit downgrades if they do not act to mitigate their climate risks.

Moody’s Investors Service states: “The growing effects of climate change, including climbing global temperatures, and rising sea levels, are forecast to have an increasing economic impact on US state and local issuers. This will be a growing negative credit factor for issuers without sufficient adaptation and mitigation strategies.”

Will Wynn, former mayor of Austin, TX

Former mayor of Austin, TX and co-author to this piece, Will Wynn noted, “Historically, credit rating agencies handicapped a city’s likelihood to respond to a downturn. These agencies now seem to be far more interested in cities’ policies and investments in advance of an inevitable downturn, including those that are climate-related.”

Increasingly, credit rating agencies are under pressure from investors and policy makers who see significant gaps between climate risk and city’s mitigation actions.

The rating agencies are already factoring into their muni credit rating whether or not cities are taking actions to protect their residents.

Smart surface strategies give cities a strong set of risk mitigation tools. (For detailed discussion see the 300-page report: Delivering Urban Resilience on the Smart Surfaces website.)

Adoption of citywide programs like green and reflective roofs and porous pavements can make them far more resilient. Smart surfaces directly mitigate the urban heat island effect, urban flooding from surface water accumulation and sewer back up.

In 2019, a group called Network for Greening the Financial System, representing many of the world’s major national banks, released a review mapping how climate change impacts financial risk, including for municipalities.

They found that the key intermediaries between physical risk and financial stability risk are changes in residential and commercial property value, lower household wealth, reduction in corporate earnings and increased liability.

Impact of Climate Risk on Cities, Businesses and Residents

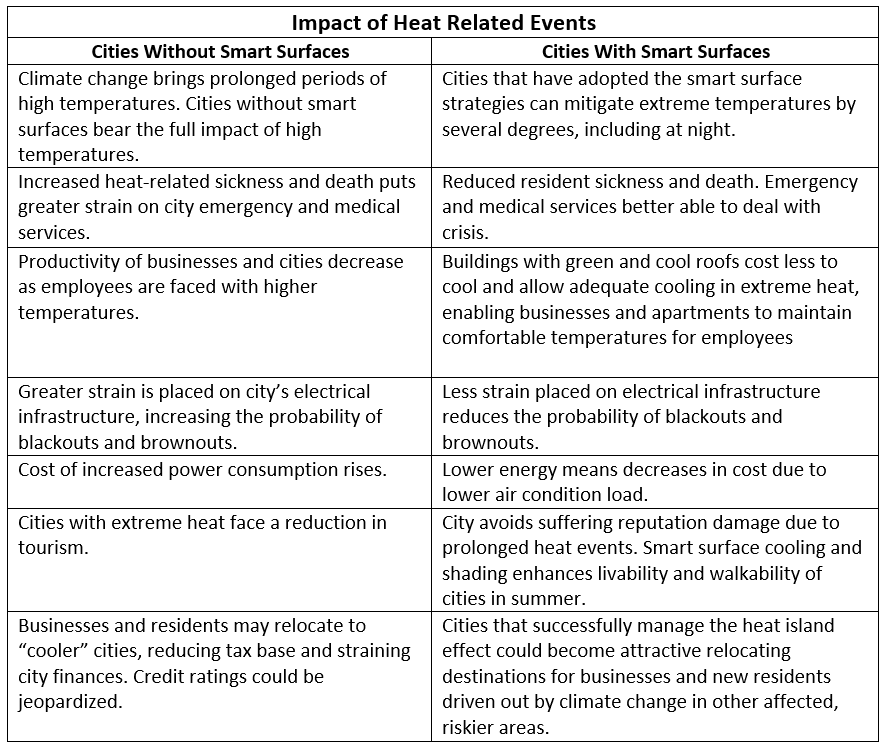

As discussed earlier, accelerating climate change directly exposes cities, their residents and businesses to an increasing range of weather risks.

These include prolonged heat waves; flooding from severe rainfall events and from sea level rise; and hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfire and prolonged droughts, all of which are occurring with greater than historic frequency and with increased severity.

As Moody’s notes, smart cities will choose to manage these risks in a prudent and proactive manner.

Smart surfaces mitigate and reduce the risks and costs of floods, heat waves and other risks that can have a disruptive — even deadly — impact on residents of cities.

Heat Islands

Among all the climate-related disasters that are confronting cities, heat waves are the deadliest.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, extreme heat now causes more deaths in U.S. cities than all other weather events combined.

Extreme heat causes a large range of illness and sickness, up to and including death. Longer, more frequent heat waves — like the one affecting most of the nation in summer 2018 — are expected in the future, meaning summer’s death toll will rise.

Stephen Bushnell, co-founder, Sustainable Disaster Response Council

In late June 2018, dozens of people were killed across the U.S. and in Canada — including 28 people in Montreal — after much of the country experienced multiple days that were 100 degrees Fahrenheit and higher.

The following week, much of California experienced a heat wave with all-time record-setting temperatures, and another deadly heat wave swept through the Southwest later in July.

At one point, a heat dome of hot air pushed temperatures above 90 degrees in 44 of 50 states.

More than 155 people died from heat-related causes in the Phoenix area in 2017, leading to former Phoenix Mayor Greg Stanton deeming it a public health crisis.

Elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere, other cities have seen high death tolls.

In 2018, Japan recorded an all-time high of 106 degrees as a total of 96 people were killed across the country. In Seoul, 29 people died during a two-week stretch of 95-degree days. Two separate deadly heat waves struck Europe in 2018.

Excess heat reduces productivity, especially for workers working outside on roads, in building and facility maintenance, on power lines, electrical maintenance, etc.

A 2013 NOAA study projected that heat-stress related labor capacity losses would double globally by 2050 with a warming climate. The impact is expected to be felt the most by those who work outside or in hot environments, such as firefighters, bakery workers, farmers, construction workers, factory workers and others who will be forced to slow down due to increases in heat and humidity.

The Fourth National Climate Assessment documents that extreme weather and climate-related events can have lasting mental health consequences in affected communities, particularly if they result in degradation of livelihoods or community relocation.

Adaptation and mitigation policies and programs that help individuals, communities and states prepare for the risks of a changing climate would reduce the number of injuries, illnesses and even deaths from climate-related health outcomes.

In addition, heat waves place a significant strain on aging electrical grids.

Summer brownouts and blackouts are common. Heat related power outages and rolling blackouts were common in the U.S. during the summer of 2018. See for example:

- Heat Waves Leaves Thousands of Edison Customers Without Power — Long Beach Post

- Massachusetts Hit With Power Outages as Heat Sets In — Boston Herald

- Officials Managing State’s Electrical Grid Warn of Possible Rolling Blackouts. — CBS Sacramento

How Smart Surface Adoption Fights Heat Risks Flooding

Flooding

Increased costs due to climate change is particularly apparent in coastal cities where real estate insurance costs are rising due to increased flooding risk and hurricanes.

A recent Freddie Mac publication identifies climate change related flooding as a major threat to many cities, one which will get larger and costlier with increasing severity of climate change related flooding.

The report states: “While technical solutions may stave off some of the worst effects of climate change, rising sea levels and spreading flood plains nonetheless appear likely to destroy billions of dollars in property and to displace millions of people.”

Floods result in direct damage to city property, homes and commercial businesses. Generally, only some of the damage is covered by insurance, leaving much or most of the cost to repair and rebuild on the shoulders of homeowners and businesses.

As noted earlier, most U.S. property insurance policies exclude coverage for flood damage. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was created in 1967 to fill this gap, however only a fraction of properties damaged by flood in Hurricanes Harvey and Florence had any flood insurance.

Even when flood insurance is in place, homeowners and businesses must pay all out-of-pocket costs for living expenses or loss of business income while the flood damage is being repaired.

There are also significant potential losses that are not insured, such as business income or resident’s additional living expense.

Cities must continue to provide services as well as manage the emergency.

Further, NFIP coverage pays losses on an “actual cash value” basis, which is often far less than the cost to repair or replace the property.

Following a flood, renters and businesses may be forced to relocate to other communities and many never return. If there is no flood insurance to pay for repairs, buildings may simply be abandoned, becoming a blight on the community and lowering the tax base. This downward spiral reduces revenue and threatens the city’s credit rating.

Climate change has increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including heavy rainfall that, unless mitigated by smart surface strategies, results in surface water accumulation, sewer back up and overflow of rivers, streams, and other bodies of water.

Cities have the capacity to move from dark, impervious surfaces to reflective, porous and green surfaces. Or, as Moody’s Cahill notes: “Business, economic and financial factors as well as technological solutions are expected to mitigate some of these risks, especially for businesses and institutions that have longer time frames to adapt and that also possess inherent credit strengths”.

Smart surface strategies lessen the impact of storms, storm water retention and runoff. Municipalities that implement a smart surface strategy secure risk reduction and resilience benefits, which accrue and expand over time, offsetting climate change and protecting cities from increasing heat and storm severity.

Rob Jarrell, analyst, Capital E

Adopting smart surfaces can reduce city temperature faster than climate change is expected to increase it.

That is, smart surfaces provide a pathway for cities to become cooler as the world warms — and to do so in a way that saves money and reduces urban global warming.

Smart surface strategies, including green space with trees, roof design and porous pavement, can significantly reduce the risks and financial losses associated with surface water and sewer backup.

Cities that implement smart surface strategies will enjoy significant financial advantages over cities that do not over the coming decades, and this divergence in financial performance will result in better credit ratings for forward thinking cities.

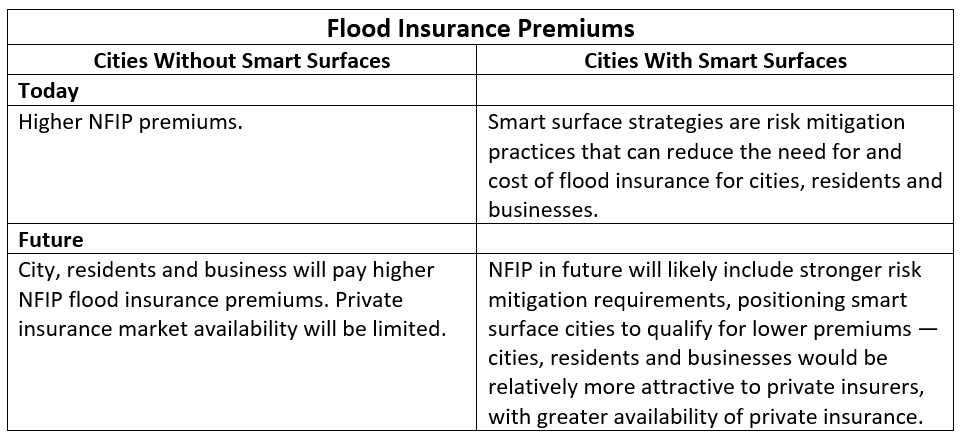

Flood Insurance

In the United States, the lion’s share of flood insurance is provided by the NFIP, which was formed in 1967 as U.S. private insurers had been reluctant to provide flood coverage.

Private insurance for homeowners, public entities and businesses excludes all forms of flood (surface water, waves, tidal water, overflow of a body of water, water which backs up through sewers, drains or sumps). NFIP already offers discounts to communities that have taken meaningful adaptation actions.

However, the NFIP “is not designed to handle catastrophic losses like those caused by Harvey, Irma and Maria,” Mick Mulvaney, the director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, said in a letter to members of Congress after the three huge hurricanes barreled into the United States this season.

Mortgage lenders require flood insurance for properties in the 100-year flood plain. Otherwise flood insurance is voluntary. It is rarely purchased when not required.

For example, only 20% of properties damaged in Harvey’s 2017 floods had flood insurance, while even less of the Carolinas had flood insurance when hurricane Florence struck.

Private insurance accounts for 15% of the total flood insurance premiums in the U.S.

The amount of private flood insurance premiums grew by over 50% in 2017.

Private insurance is not subsidized by the government and is generally much more expensive, more accurately reflecting the actual flood risk. Private insurers have three approaches to flood insurance: (1) providing coverage excess of NFIP coverage for large property owners; (2) providing coverage in program and group policies for clients (that can include cities); and (3) cherry picking the best (lowest) risks through risk analysis and modeling.

Flood insurance rates will increase substantially and risk management requirements will become more stringent.

In March 2019, FEMA announced that beginning in 2020 they will begin using computer modeling to price federal flood insurance. Referred to as “Risk Rating 2.0,” the new plan is expected to increase flood insurance premiums.

Strong risk management programs would reduce losses, help avoid loss of coverage and could alleviate rate increases — and might even lead to rate reductions. NFIP flood rating plans will continue to include discounts for cities that have taken steps to mitigate flood risks. Municipalities and their residents and businesses that implement smart surface strategies should realize the benefits of lower premiums.

Private insurers will continue to screen, identify and insure the best risks and will continue to use sophisticated modeling and analytics to cherry pick the best risks — giving cities that have adopted smart surface strategies a distinct advantage as well.

Cities and their residents and businesses that adopt smart surface strategies will be better positioned to manage the impact of flood risk on their finances than cities that have not.

This advantage exists today and will become more pronounced over the next several decades. There will likely be a significant divergence in municipal finances and credit rating between those that adopt smart surfaces city-wide and those that do not.

Some of these differences are summarized in the table below:

Financial Impact of Smart Surface Strategies for Flood Risks

The financial benefits of adopting smart surface strategies may amount to a few hundred dollars for each insured property today and could increase 5- to 10-fold over the next 10 to 20 years.

For many home buyers and owners, the cost of flood insurance is a growing burden. As premiums rise, property values fall, a trend already hurting home prices in places like Atlantic City, N.J., Norfolk, Va., and St. Petersburg, Fla.

According to economists, the phenomenon of rising insurance premiums making homes less affordable and less valuable will increase as the federal government shifts away from subsidizing flood insurance rates to get premiums closer to reflecting the true market cost of the risk.

As accelerating climate change increases the frequency of severe storms, the financial benefits of adopting smart surfaces will increase. Cities that have not implemented these mitigation strategies will be at a greater risk of credit downgrade as their tax base erodes and costs rise, as summarized below.

Now and Later: The Financial Impact of Flood Losses on Cities

Today, when it comes to cities without smart surface strategies in place:

- The NFIP settles flood losses on an actual cash value basis (replacement cost minus depreciation). Flood loss commonly exceeds NFIP limits, and some property (e.g. papers and records) is not covered. Additional city expenses are also not covered.

- If there is no insurance, the loss to the city is unprotected.

- Residents and businesses face similar financial risks as cities, and recovering from even a minor flood can take months, with competing local demand for contractors and construction materials. Some businesses and residents typically relocate permanently following serious flooding.

- The sales tax and real estate tax bases are eroded.

- Cities that have not adopted smart surface strategies face increased climate related risk. City budgets are strained and residents and businesses incur losses, reduced municipal capacity to provide basic services.

- Cities that have not adopted smart surface strategies face increase to mold and health risks and costs. Buildings that can no longer be occupied diminish in value and erode the cities’ tax base.

On the other side, cities with smart surfaces today see how:

- Smart surfaces mitigate flooding and costs (for example, losses from backed-up sewers). Avoiding these losses can significantly reduce direct financial losses of the cities and their businesses and residents.

- Smart surface strategies can protect residents and businesses against surface water and sewer back-up losses.

- The city can shield its tax base from financial costs of floods. Removal and disposal of flood debris presents significant costs. Much of the material is toxic, and debris puts an additional strain on already over-taxed landfills.

- Mold often follows flood losses. A serious mold problem can make a property untenable. Cities that adopt smart surface strategies will experience fewer and less costly flood, contamination and mold events, minimizing their exposure to this risk.

In the future, cities without smart surfaces will continue to face multiple flood events that would likely reduce a city’s tax base permanently, while increasing muni costs.

But for the cities of the future with smart surface strategies in place, they will be better prepared to handle the increase of severe storms forecast by climate scientists.

An In-Depth Look at Real Estate

Pricing of homes at risk from climate change are already experiencing significant losses in value in some markets.

Greg H. Kats, CEO, Smart Surfaces Coalition

In May 2018, a Bloomberg article entitled “Climate Change Turns Coastal Property Into a Junk Bond” summarized recent research showing that climate impact is already showing up in the value of coastal real estate. Houses exposed to a sea-level rise of between 0 and 6 feet sold between 2007-2016 at a 7% discount relative to houses a similar distance from the beach that are higher in elevation.

As Bloomberg noted, this price differential occurred even before the damage from hurricane Harvey. Housing areas where people report more worry about climate change experience greater price reductions.

Nationally, median home prices in areas at high risk for flooding are 4.4% below what they were 10 years ago, while home prices in low-risk areas are up 29.7% over the same period, according to the housing data.

The market pricing of homes at risk from climate change are already experiencing significant losses in value.

As climate-change-driven heat and severe weather events worsen, the value of buildings and businesses will be increasingly differentiated on the basis of risk — and whether or not they are in cities that have adopted smart surface policies.

Legal Liability

Cities may be potentially liable for damages suffered by residents for negligence as a result of not adopting smart surface strategies.

Such damages could be large.

This is a complex subject, given the laws and court precedents of all 50 states and, in some cases, a city’s ability to claim sovereign immunity.

As an example, requirements in California (California Civil Code Section 1714) for meeting the test of legal negligence, include:

- the foresee-ability of harm to the injured party;

- the degree of certainty they suffered an injury;

- the closeness of the connection between the defendant’s conduct and the injury suffered;

- the moral blame attached to the defendant’s conduct;

- the policy of preventing future harm;

- the extent of the burden to the defendant and the consequences to the community of imposing a duty of care with resulting liability for breach; and

- the availability, cost and prevalence of insurance for the risk involved.

As smart surfaces become more widely adopted, cities that choose not to implement smart surface strategies risk falling under the definition of negligence.

This risk to cities would likely increase if uninsured disasters lead claimants to search for deep pockets.

Legal action is pending against private firms that have negligently failed to act during a climate crisis. For example, a Texas grand jury recently indicted chemicals manufacturer Arkema North America Inc. and two of its executives for releasing emissions that allegedly endangered the public after a 2017 hurricane.

Air quality problems also pose a very common urban risk that can be reduced cost effectively through adoption of smart surface strategies.

As extensively document by the Smart Surface Coalition, smart surfaces adoption city-wide would both reduce liability risk and deliver net present savings of billions of dollars to mid and large size cities such as Washington DC and Philadelphia.

As noted in the Fourth National Climate Assessment 2018: “More than 100 million people in the United States live in communities where air pollution exceeds health-based air quality standards. Unless counteracting efforts to improve air quality are implemented, climate change will worsen existing air pollution levels. This worsened air pollution would increase the incidence of adverse respiratory and cardiovascular health effects, including premature death.”

Cities that invest in smart surfaces will reduce their exposure to legal liability around health property and other dimensions of risk.

Conversely, cities that continue to specify dark, impervious surfaces, thus exposing their citizens to greater risks and illness can expect to face more costly legal action and lawsuits. &

Here’s How Cities Can Reduce Climate Change Risk

Climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme and costly weather events, but cities have an opportunity to mitigate the risks.

A deeper dive into the impact increased severe weather events have on a city’s credit risk, looking at heat waves and flooding as prime examples.

How Smart Surface Strategies Are Increasing Resiliency for Cities Faced With Climate Change Risk

A smart surface strategy can increase climate change resiliency and decrease credit risk and its costs.