This Is How Face-to-Face Interactions Transform Your Company’s Safety Performance and Program Awareness

The University of Pennsylvania can lay claim to an impressive array of firsts. It is America’s first university. It established the first student union and the first double-decker college football stadium. UPenn can also boast the world’s first collegiate business school and the first woman president of an Ivy League institution.

But UPenn, the largest private employer in the city of Philadelphia, is not the first complex organization to struggle with a decentralized workers’ comp program.

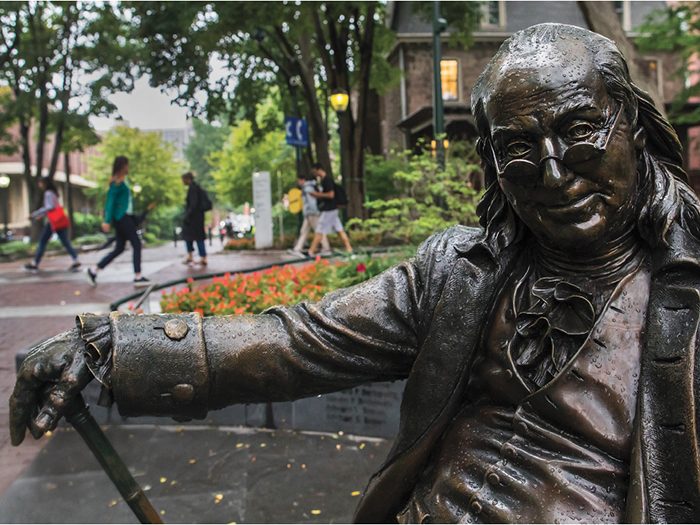

Ben Evans, associate vice president, risk management and insurance, Division of Finance, University of Pennsylvania

In 2008, Ben Evans joined the university as executive director, risk management and insurance in the Division of Finance, later advancing to the position of Associate Vice President. Its workers’ comp program at the time was functional, but hardly thriving, he said.

“We just kind of made sure that people got paid,” he said. “There were no angry employees — people were getting their checks when they were supposed to.”

Though there were safety initiatives in place, along with a strong occupational medicine program, there was basically “no culture of health and awareness, no return to work, just none of that,” he said. “There was no glue … no bloodline, if you will, running through it all.”

For UPenn’s 32,000 employees, which includes the largest private police force in Pennsylvania, Evans was determined to do better. He made it his team’s mission to put workers’ comp and safety on everyone’s radar, and he has overwhelmingly succeeded, earning the University of Pennsylvania a 2018 Teddy Award.

Building Up Workers’ Comp

Evans’ first order of business was to hire a full-time workers’ compensation manager to help him give UPenn’s program an overhaul in both structure and identity. He hired Monica Dagger in 2009. Evans also cut ties with the University’s longtime TPA and partnered with PMA Management Corp in 2010.

For Evans and Dagger, the first order of business was visibility. Across the University’s 12 schools, 75 operating subsidiaries and various research facilities, knowledge of the workers’ comp program was inconsistent. Worse, there was a general discomfort attached to discussing hazards and injuries, and a certain level of stigma existed. The program needed an image makeover.

There are a variety of ways Evans’ office could have opened that dialogue, from distributing slick new brochures or launching a university-wide email campaign. But Evans understood that getting face-to-face with every stakeholder was the only way he was going to achieve the level of engagement he needed in order to make substantive change.

“I was brand new. I knew the people I interviewed with, I knew who was on my staff. But I didn’t know the rest of this massive population that we have here,” said Evans. “So, it was my job to get out and build those relationships.”

“Where technology has helped us produce better analytics and data, it has done nothing to take away the personal relationships that are necessary to make it all work.” — Ben Evans, associate vice president, risk management and insurance, Division of Finance, University of Pennsylvania

Through each one-on-one conversation across the vast campus, Evans and his team built up relationships and trust, nurturing the buy-in they would need to make their program changes work.

“It really is all about relationships and it’s building bridges not burning bridges — it’s still a people business. It always has been, it always will be. Where technology has helped us produce better analytics and data, it has done nothing to take away the personal relationships that are necessary to make it all work. Relationships change culture, relationships are tangible. And so that’s the way I operate.”

Evans built strong ties with the Environmental Health and Radiation Safety (EHRS) department and Penn Occupational Medicine, as well as the Facilities and Real Estate Services (FRES) department, which includes all trades and housekeeping personnel.

The philosophy underlying many of UPenn’s successful strategies is the understanding that innovation isn’t necessarily rocket science. Sometimes simple or common-sense changes will net the most powerful results.

But those simple things aren’t always obvious to the people performing the work every day, who are either too focused on getting the work done or too stuck in the “this is the way it’s always been done” mindset to spot opportunities.

“Sometimes it just takes an outsider,” said Dagger, UPenn’s workers’ compensation manager.

“You just watch the things that are happening. What might not be obvious to one person might be obvious to the person standing right next to him, who’s asking, ‘Why are you doing it like that?’ ”

Case in point: Evans’ team identified that the University Laboratory and Animal Resources division had some of the highest injury rates at UPenn. PMA was called in to provide recommendations, and on-site visits were arranged with EHRS staff as well as Penn Occupational Medicine.

Through this high level of eyes-on attention, the University made several simple but pivotal changes. Handheld nozzles on the hoses used to spray down animal cages were replaced with lightweight ergonomic adjustable nozzles that reduced strain on hands and wrists. Hand and wrist injuries were virtually eliminated.

High-capacity electric pallet jacks were purchased to handle bags of feed and heavy animal bedding, reducing lifting injuries. New procedures were formalized for cage handling, cage washing and trash disposal. The maximum weight for bags of dirty bedding was reduced to 35 lbs. Tilt carts were purchased to take trash to the dumpster.

Similar changes have been made across departments campus-wide, from backpack vacuums for housekeeping staff to the elimination of 50 lb. bags of masonry material to phasing out manual screwdrivers in favor of electric ones.

Mobile tool carts and saws with SawStop (safety) technology have also been added. Changes were also made to the footwear requirements for trades and housekeeping staff.

On their own, many of these departments may not have had the budget available to purchase even something as simple as electric screwdrivers, said Dagger.

That’s why UPenn’s Office of Risk Management takes on those expenses when departments need equipment that will mitigate injuries. In the end this modest investment will go a long way to prevent injuries.

“It’s cheaper for us to pay for an electric pallet, for example, than to pay for multiple workers’ comp claims because people are getting injured lifting these bags,” she explained.

“So ULAR might not have the money in their budget for it, but compared to the cost of multiple claims, it’s a minor expense for our office.”

The department has the numbers to back up their investments.

“Prior to [when we came on board], they were spending $12 to $15 million a year on workers’ comp and now the average may be $6 to $8 million,” Dagger added.

Getting Back to Work

Lost time was problematic for the University when Evans came aboard. With no light duty program to speak of, injured workers would recover at home, leaving their departments pinched.

“[Say I lead] the Division of Public Safety and one of my employees is out on workers’ comp. I lose productivity, and if there’s a pattern that develops in that department, morale goes down because somebody else has to pick up the load,” said Evans.

More than half of workers’ comp injuries involved housekeeping staff, so Evans’ team partnered with FRES and launched the Light Active and Modified Duty Program (LAMP) for the department, working very closely with Penn Occupational Medicine.

“Sometimes it just takes an outsider. What might not be obvious to one person might be obvious to the person standing right next to him, who’s asking, ‘Why are you doing it like that?’ ” — Monica Dagger, workers’ compensation manager, University of Pennsylvania

The variety of tasks performed by the department facilitated blended solutions, whereas an employee who couldn’t bend could dust above his/her shoulder, while an employee who couldn’t reach overhead could dust below the shoulder, for example.

In 2017, housekeeping employees accumulated more than 1,143 days on light duty programs. Light duty and limited duty have also expanded to include trades personnel as well as the UPenn Police Department, which includes 120 officers and 55 civilian personnel.

Injured officers help ensure student and staff safety by remotely monitoring key locations via the University’s expansive CCTV system —Virtual Patrol.

Evans’ team is highly motivated to find new opportunities to serve the student population by protecting the employees who keep UPenn in motion.

“They’re constantly asking ‘Why?’ and ‘How?’ and ‘How can we do things better?’ ” said Matthew Stairs, client service manager with PMA Management Corp.

“They’re willing to put the time and resources in, they’re committed to doing everything they can to improve the program.”

Evans said he feels gratified to be a part of UPenn’s program and to be able to impact the well-being of his constituents.

“I go home a lot of nights with my head spinning and complete brain drain, but every night I know there is at least one thing that I added value to that day. It’s a great industry.” &