Supply Chain

Bringing it Home

Karen Kane, a women’s apparel manufacturer in Los Angeles, is just one of the increasing number of companies that is returning much of its offshore manufacturing operations to the United States.

“It was a long-term decision,” said the company’s CEO, Lonnie Kane, to Bloomberg TV. “When you start looking at duty costs and transportation costs, we felt that we could very economically produce goods” in the United States.

And that doesn’t even take into account the shortened supply chain that increases supplier visibility due to the ever-more-popular move known as reshoring.

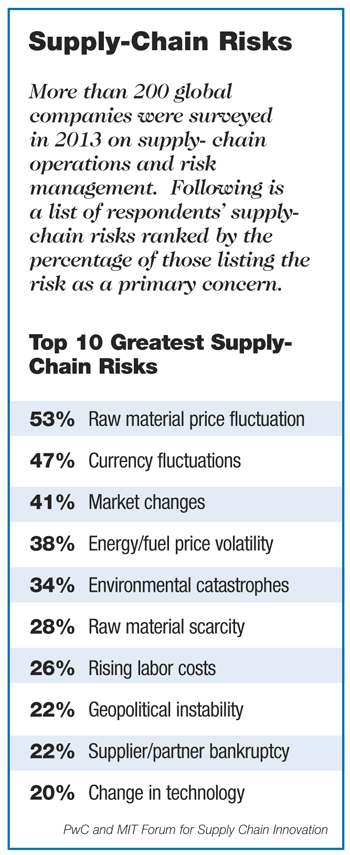

“Supply-chain risk management is already becoming a top five boardroom issue for most companies,” said Jamie Crystal, executive vice president of Crystal & Company, a New York-based brokerage. “The ability to manage supply chain is often the difference between success and failure.”

By returning manufacturing operations to the United States, companies “are substantially decreasing their risk,” he said.

But for all of the advantages involved in reshoring — and there are many — challenges remain. Supply-chain risk doesn’t disappear just because a supplier is within driving distance instead of 13 hours of flight time away. In some ways, a regional approach to suppliers could offer more risk, such as in the event of a regional weather event.

Karen Kane Chief Executive Officer Lonnie Kane talks about the company’s decision to reduce the amount of clothing it produces in China and increase U.S. manufacturing.

And for all of the preventive safety rules in the United States, ramping up productivity could mean increased workers’ comp claims.

Reshoring Increases

An oft-touted 2012 study by the Boston Consulting Group projected that increased manufacturing in the United States resulting from reshoring could add 2.5 million to 5 million jobs by 2020.

Some of the bigger companies involved are General Electric, which will manufacture some appliances in Kentucky; Lenovo, which will make computers in North Carolina; and Apple, which has said it will begin making Macs in the United States.

In a September 2013 report focusing just on China, BCG found that more than half of large U.S.-based manufacturing executives plan or are actively considering plans to bring back production to the United States. The percentage of executives planning to reshore rose to 54 percent in 2013, compared to 37 percent in 2012.

The top three reasons? Labor costs, proximity to customers and product quality. Other reasons cited were access to skilled labor, transportation costs, supply-chain lead time and ease of doing business.

The tsunami and earthquake in Japan in 2011 and the flooding in Thailand in 2012 and 2013 caused many companies to re-evaluate their supply-chain risks, said Chad Moutray, chief economist at the National Association of Manufacturers.

The United States is seen as a more viable location for production investment, he said, because of an energy advantage resulting from domestic fracking of shale gas, robust U.S. productivity rates, and rising labor costs overseas — such as in China, where salaries have doubled since 2008 and are still increasing about 13 percent year over year.

That doesn’t mean domestic supply-chain risks don’t exist, however.

Perry Rotella, group executive, supply-chain risk analytics at Verisk, said manufacturers have supply-chain risks regardless of where their suppliers are located. “But,” he said, “there is more visibility into the United States. You have better data to assess risk and more visibility into where you are sourcing.”

That means companies have more information about weather patterns, catastrophic risks, property construction and the financial viability of their suppliers and distribution centers. They also have a more transparent and consistent legal and regulatory system, and no worries about currency fluctuation, geopolitical upheaval or nationalization threats.

Plus, there is less potential risk to reputation, as opposed to when a company’s suppliers are located in countries where safety standards or employment practices do not measure up to U.S. laws — or consumer expectations.

Those reputational risks can range from the global apparel companies whose products were manufactured in the Bangladeshi factory that collapsed and killed 1,100 workers; to Apple’s supplier Foxconn, which needed to install “suicide nets” to prevent unhappy workers from jumping to their deaths; to Mattel, which had to recall nearly 1 million toys because a Chinese-based supplier had been using lead-based paint, in contravention of the company’s requirements.

“Companies are being held accountable not just for their own actions, but for the actions of their suppliers, and it gets even more complicated when you have multiple tiers [of suppliers],” Rotella said.

According to a KPMG Global Manufacturing Outlook study, nearly half of the surveyed companies said they lack visibility into their supply chain beyond Tier 1 partners, or their direct suppliers. And only 9 percent said their company can assess the impact of supply-chain disruptions within hours; that number increased to 20 percent for companies with revenues of $5 billion or more.

Nearly six in 10 global manufacturers said they plan to regionalize and localize their supply chains to improve supply-chain risk management.

In many cases, experts said, manufacturers will need to source some materials or parts from overseas suppliers, even if they bring much of their operations to the United States.

A Regional Approach

What McKinsey & Co. calls “next-shoring,” or placing manufacturing facilities near demand and innovation, is a growing trend, experts say. Next-shoring does not necessarily mean locating facilities in the United States, just near market demand.

It allows manufacturers to customize their product and respond to changes in demand because they are closer to their market, said Gary Lynch, founder and CEO of The Risk Project LLC. While that seemingly offers a more stable environment, “the reality is it complicates things a little more.”

When manufacturers use local suppliers, a regional event, such as a Superstorm Sandy, can greatly affect production or transportation. Plus, when the company buys on a global basis, it has more leverage over its primary suppliers, Lynch said, instead of when it sources smaller quantities from suppliers near each facility.

And if companies don’t have resiliency built into their production process — such as secondary sources, distribution centers or transportation routes — they can face some real challenges. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, need Food and Drug Administration approval prior to changing suppliers of sterile water, which is used in drug production. Such approval, Lynch said, could take one to two years.

“This becomes a real hornet’s nest of understanding interdependencies among not only different companies, but different industries, so you can get an aggregated exposure,” he said.

In addition, whenever a company ramps up production it can mean less time for maintenance of equipment, which can break down and increase hazards for workers, said Jim Mandes, manufacturing product manager, Travelers.

Ramping up production also means new workers may need to be hired, employees may be working longer hours, or more shifts may be added to the production line. That can increase workers’ comp exposures, especially if companies don’t have the time to devote to necessary skills and safety training, he said, noting that his company works with clients to analyze risk and offer on-demand training.

Plus, if a facility is being retrofitted instead of purpose-built, there may be environmental issues due to previous use that need to be explored, he said.

Risk Transfer and Mitigation

Most companies just don’t have the necessary methodology in place to quantify the financial impact of supply-chain disruptions, said Crystal. That’s mostly because the necessary information resides in a variety of departments, including sourcing, logistics, operations and finance.

“Many companies have a $5 million or $10 million limit for supply-chain disruption, but in most cases, that amount of insurance is totally inadequate,” he said.

“Many companies have a $5 million or $10 million limit for supply-chain disruption, but in most cases, that amount of insurance is totally inadequate,” he said.

“The insurance industry is prepared to provide more coverage but they require extensive underwriting information. How does risk management obtain underwriting information from 100 different third-party suppliers? It can be quite challenging,” he said, noting that his company has some online tools to assist in that process.

Collecting accurate and detailed supplier data for underwriting is the “primary barrier” to insuring supply-chain risk, said Lynch of The Risk Project. Some companies in the chemical industry, for example, can have 20,000 to 30,000 suppliers.

Placement of supply-chain or trade-disruption insurance is “very, very limited,” he said.

“It’s a real challenge,” said Lynch, who previously was head of Marsh’s global supply chain risk management practice. “Now that cyber has taken such a front seat, I see it as less likely that companies will prioritize the collection of the right data and get the [supply-chain] exposure underwritten.”

Zurich and AIG are two insurers that offer structured supply-chain solutions that do not require physical damage to trigger coverage, such as contingent business interruption coverage would require, experts said. Munich RE, Lloyd’s of London, Berkshire and other reinsurers also can provide coverage, although on a more customized basis.

About 40 percent of all supply-chain disruptions occur below Tier 1 suppliers, said Linda Conrad, director of strategic business risk, Zurich Global Corporate. “That’s a supplier’s supplier, or even a supplier’s supplier’s supplier. It’s caused by someone you don’t have any direct control over.”

Zurich’s Supply Chain Risk Assessment and Insurance product is an “all risk” policy that can cover both physical and non-physical damage disruptions such as strikes, IT and power outages, insolvency and transportation issues, she said. It can protect named supplies and suppliers, based on a pre-agreed limit up to a maximum aggregate limit of $100 million per customer.

It does not cover product quality or product recall.

Only 8 percent of companies have business continuity plans with their suppliers, Conrad said, noting that it is the “extra expense” of recovering from a disruption — such as retooling a factory or changing a shipping method — that is most costly to companies.

“It does take some effort” to compile the necessary information needed for supplier risk assessments, she said, but noted that much of that information may already be required for business interruption and contingent business interruption coverage.

Zurich has seen “a pretty big uptick” in its supplier risk assessment services, she said, although that does not necessarily lead to the purchase of insurance.

When looking at insurance and risk assessment, Lynch said, companies should focus on the suppliers that contribute to “key value streams” of their company. So, for example, a company like Apple might prioritize limited risk resources on a more detailed view of suppliers for the iPhone instead of the iPod, because of the former’s much more significant impact on the company’s performance.

Preventive Measures

But insurance can only do so much. It will always be better to have resiliency built into the sourcing, production, distribution and supply-chain network.

“There is no safety net for stabilizing earnings or finances via insurance,” Lynch said. “It all falls back on mitigating the risk.”

Historically, disruptions are difficult to recover from, resulting in 10 percent lower sales, 11 percent higher costs and a 25 percent decline in market share. About 40 percent of companies that suffer an extended disruption never recover, according to Zurich.

Risk managers need to make sure potential disruptions and production delays can be somewhat offset by having secondary suppliers, sources of material and transportation alternatives. They should also examine whether their primary suppliers have their own built-in resiliency, such as having multiple locations where they can produce or source components.

“You have to take that business continuity mind-set and extend it out of your four walls and into your supply chain,” said Rotella of Verisk. “You have to have visibility and understand the full landscape.”

He said that Verisk offers predictive models that help determine the impact of weather and natural disaster on meeting product demand, and is now working on creating a predictive model to flag suppliers that may offer a financial risk. “What we are trying to do is take our risk models and apply them to supply-chain optimization,” he said.

For manufacturers, it doesn’t matter if disruptions are traced to Japan, Vancouver or California, if the result is that a manufacturer has to wait more than a year to get its products back on the shelves.

“We see that this is top of mind for CFOs and treasurers,” Conrad said, “because ultimately they are the ones that will have to pay for any disruptions, lost sales, or more importantly, the extra recovery expenses.

“If the CFO and the treasurer are concerned about this, then probably the risk management community should be as well.”