Specialty Insurance

A Nuclear Dilemma

By the end of 2016, Southern California Edison will select from among three teams of contractors vying for the $4.4 billion job of decommissioning its San Onofre 2 and 3 nuclear power reactors in San Clemente, Calif.

Even before the lucrative contract is awarded, the jockeying for it marks a significant shift in risk management and planning for the entire nuclear industry: the emergence of a robust, competitive market to manage and execute the physical job as well as provide financing, insurance and risk management services.

The primary drivers of nuclear power plant decommissioning changed through the years, said Dan McGarvey, managing director of the U.S. power and utility practice at Marsh.

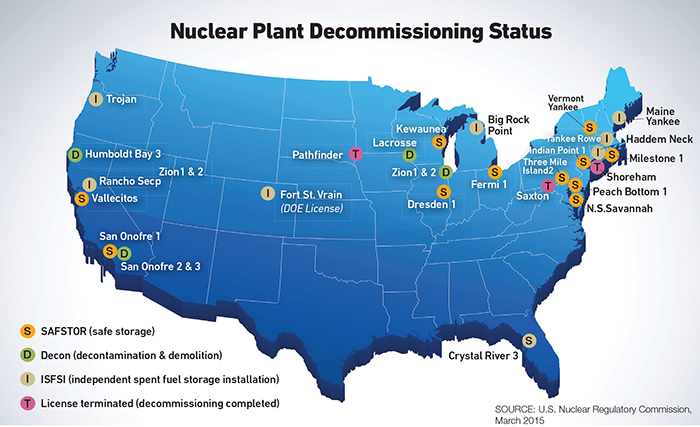

As of July, the NRC listed 19 reactors undergoing decommissioning. That number is expected to grow.

“The classic decommissioning was because of technologies that either ran their course or failed to live up to their potential. Others were driven by the untimely requirement to replace major components or effect expensive repairs,” he said.

In the future, the main driving forces are likely to be the dictates of energy markets, McGarvey said.

“Because of the unprecedented low cost of natural gas, some nuclear stations have been determined to be not economically viable.”

Whether utilities will be able to scrape together the funds to decommission plants is a question mark.

According to Arun Mani, a partner at Oliver Wyman, nuclear plants are facing a tough economic environment in large part because of low natural gas prices, which have pushed down wholesale power prices.

Rob Battenfield, senior vice president of downstream energy, JLT Specialty USA

With an average operating cost of $35/MWh, nuclear plants are battling to stay afloat. In an environment of falling gas and power prices, nuclear power is often out of the money.

“When a nuclear plant closes,” said Mani, “especially if it is retired prematurely, it adds to a growing gap, the difference between funded and unfunded liabilities for decommissioning. Those estimated costs industrywide have risen by about 60 percent since 2008 and now stand at $88 billion, of which 31 percent, or $27 billion, is unfunded.”

“The underfunded or even unfunded costs of decommissioning worldwide is a huge issue,” said Rob Battenfield, senior vice president of downstream energy at JLT Specialty USA.

From the moment a utility is granted a license to operate by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), it is required to accumulate a trust fund against the ultimate cost of decommissioning. Historically, those costs have run about $480 million for one reactor, and about $800 million for a two-unit complex.

There are many variables in the matrix of operating or closing a nuclear plant, of which the mandated and actual size of the trust fund are only two. And in essence the trust fund is something between a running start and a show of good faith.

“If a utility is supposed to have $300 million in the trust fund, and it has that or even a little more, but the actual cost of closing the facility is going to be $400 million, then the utility is on the hook for that full $400 million,” Battenfield said.

The market fluctuations that vex individuals planning for retirement do the same to trust funds, only on a larger scale.

“If a utility was planning to retire a unit in 2010, but its trust fund lost 40 percent of its value in the economic crisis of 2009, that would seem to favor safe storage for a few decades and give the fund time to recover,” Battenfield said.

According to Oliver Wyman’s Mani, “as the number of plants being decommissioned increases and the costs balloon, there are increasing fears around a potential shortfall in planned nuclear decommissioning funds.”

As of July, the NRC listed 19 reactors undergoing decommissioning. That number is expected to grow.

“In the past couple of years, about 6,000 MW of nuclear capacity has been shuttered,” Mani said.

“In all, analysts expect as much as 11 percent of the nation’s nuclear fleet will face premature retirement over the next several years.”

Decommissioning is not usually a core utility competence, as many have not performed the operation before. As a result, there’s a competitive market among major global contractors with specialization in the process.

Several utilities have transferred or plan to transfer shuttered nuclear plants — facilities, liabilities, licenses and trust funds — to those contractors. One example that is nearing the end of the process is Zion 2, in Illinois.

For all the regulatory complexity, the insurance program is relatively simple.

“There is now a large contingent of experienced people who can decommission plants,” said Battenfield.

While some may pause at the idea of a company or consortium, however large and experienced, taking on a reactor decommissioning as a for-profit business, Battenfield is sanguine.

“Through the whole project the NRC does not go away. Their oversight is arduous and detailed,” he said.

Covering it All

For all the regulatory complexity, the insurance program is relatively simple. The property coverage through the Nuclear Energy Insurance Ltd. (NEIL) mutual is available, and coverage from American Nuclear Insurance (ANI) is sufficient to meet mandatory limits for third-party liability on any license holder.

Outside of those, any commercial coverage is handled the same as if a factory or refinery were to be sold.

“They start fresh with workers’ comp and other commercial lines,” said Battenfield.

“The new owners will have their own carriers that they probably would like to keep. The incumbent carriers from the utility will either try to get into the new program, or take that opportunity to get out.”

Once the decision is made to take a facility out of service, the operator must make the business decision either for prompt or protracted decommissioning. Immediate decontamination and demolition is known as “decon,” and takes several years.

The longer option involves securing and idling the site and is called safe storage or “safestor.” The facility can be kept in safestor for up to 60 years.

“The first risk management issue is which option to select,” McGarvey said.

“Prompt decommissioning involves a significant outlay of capital, but if the trust fund is sufficient it may make the most sense just to be done with it.”

If there are multiple reactors with at least one still in operation, the logical option is most likely safe storage, McGarvey said, because continuing operations offer economy of scale due to the fixed costs involved in operating an active site. But even if there are no other reactors, there are elements of risk mitigation in pursuing the safe storage option.

“Radiation begins to decay immediately after shut down, and over what could be 20 or more years of safe storage,” said McGarvey.

The ultimate cost of decommissioning could be markedly reduced because the radiation risk of fuel and components is lessened. Also, technology may improve over time and reduce future costs.

Conversely, the potential downside of waiting many years to decommission are the ongoing costs of plant upkeep, and the chance that a future regulatory climate may require levels of cleanup beyond those required today.

McGarvey summarized the step-down of coverage.

Dan McGarvey, managing director of the U.S. power and utility practice, Marsh

The chances of a radiation release significantly decrease once the reactor is no longer operating. Most utilities take their property coverage from limits as high as $2.75 billion down to the legal minimum of $1.06 billion. When the fuel stored in the spent-fuel pools cools to below a stipulated threshold, the utility is given greater latitude in selecting an appropriate first-party coverage limit.

At that point first-party coverage presents challenges in view of the need to preserve selected items of vital equipment in a facility that is otherwise slated for demolition.

“NEIL is very flexible and works well with utilities as they proceed through the decommissioning process,” said McGarvey.

Once the reactor is shut down, every asset on the site is divided into four categories for property coverage: Essential equipment is kept at replacement cost, less important components may be at actual cash value or agreed salvage value, and some buildings may be left without insurance save for decontamination coverage.

On the liability side, the first layer of coverage for an operating reactor is commercial insurance for a mandated $375 million. The next $13 billion is a mandatory retrospective pooling mechanism called the Price-Anderson Secondary Financial Protection Program that can assess up to $126 million per reactor, per incident, from all U.S. operators.

“Once the plant is permanently shut, a utility will want to get out of that club, but must petition regulators to do so,” McGarvey said.

Once the spent fuel is cooled below a certain level, the operator can further petition to reduce commercial liability limits from $375 million to $100 million.

The nuclear liability policy provided by ANI is a modified occurrence policy, which has a 10-year discovery period. As such, it’s recommended that the policy not be allowed to lapse for many years even when the reactor is fully decommissioned.

Overall, operators have to be very careful about stepping down their nuclear liability coverage.

“You start with $13 billion,” McGarvey said, “which not only responds for radiological site releases, but also follows every truckload of low-level radiological waste shipped from the site. Eventually over time you get down to just $100 million of commercial insurance as the operator’s sole protection against nuclear liability claims.” &