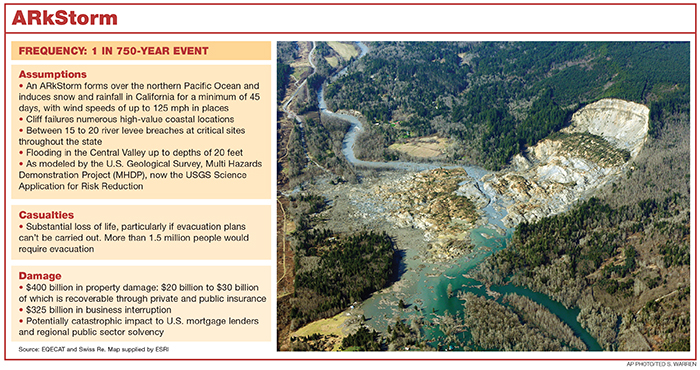

Black Swans

Welcome to the ARkStorm

The rain starts from light gray skies with modest winds. California farmers desperate for water look up from their work and raise their faces to the sky, thankful for the drops of moisture on their faces.

What the grateful farmers don’t know is that jets of warm, moist air that originated over the North Pacific have formed a massive storm system — what scientists call an atmospheric river — that is getting set to dump catastrophic amounts of precipitation on California.

First the rain comes in spurts. Then it pours and pours and keeps on pouring.

It’s more than enough to water parched almond trees and cotton fields. It’s enough to wipe those groves and fields away.

The story is that Noah built an ark to survive rain that fell for 40 days and 40 nights. This is what happens here and then some. No exaggeration.

Week after week, the rain comes relentlessly. After three weeks of solid rain, accompanied by hurricane-force winds, much of the state’s infrastructure and its flood control systems start to give way.

California’s first responders and flood control systems are prepared for storm and flood events that might come every couple of hundred years at maximum. They are not prepared for this.

The first major landslide — the first of tens of thousands — occurs at the picturesque community of Fort Bragg on the Mendocino Coast, where dozens of properties are crushed on the ocean side rocks below the town’s cliffs.

Soon, the news media report that the levees that hold back the Sacramento River from businesses and residents in the area’s delta towns are failing. Evacuations are hampered by flooded roads.

A video produced for the U.S. Geological Survey depicts a hypothethical but scientifically plausible storm impacting California.

Flooding swamps San Francisco, Los Angeles and heavily populated San Diego and Orange counties. The state’s capital, Sacramento, suffers a repeat of what it went through in 1861, when its streets were impassable and the governor had to be transported to his inauguration by boat.

The van of a family trying to drive away from the town of Pittsburg in the Sacramento River delta is swept into the surging river. A young couple and their three children are lost.

Dozens of migrant farm workers in California’s Central Valley are drowned before anyone knows they’re gone. They owned no vehicles in which to make their escape. As usual, it’s the poor who suffer the worst.

Flood waters in the Central Valley are at 10 feet and rising and will crest at 20 feet. It won’t be long before the valley is an inland lake 300 miles long and 20 miles wide. Floating on the surface of that massive lake are the bloated, decaying carcasses of thousands of cattle, poultry and swine, swept out of the largest agricultural center in the country and drowned by the storm.

Interstate 5 within the state is under water. Trucks bearing tens of millions in retail goods can’t get where they need to go. It will be weeks before I-5 is passable and it will require millions of dollars in repairs.

The ocean movement from the storm takes many of Southern California’s most treasured structures and smashes them.

The gorgeous terra cotta-roofed seaside racetrack grandstand at Del Mar — founded by Bing Crosby and some of his friends — is heavily damaged by the sea. The piers at Manhattan Beach, Hermosa Beach and Venice Beach are torn to pieces.

The flooding overwhelms coastal wastewater plants. Those residents who live along the concrete-lined Los Angeles River who weren’t forced out by the rain are driven out by sewage, as it erupts out of hundreds of manholes, turning the manmade river into a giant sewer.

The Terminal Island pumping station located between San Pedro and Long Beach is cut off by the floods. Abandoned by its 70-plus employees, raw sewage spews from it and runs untreated into the Pacific Ocean.

Chastened by its failures during the flooding in New Orleans after Katrina, the federal government moves much more quickly than it did in 2005 to support overwhelmed local and state emergency responders.

National Guardsmen and U.S. Army soldiers can help evacuate residents and hoist sandbags. They can’t, however, offer financial disaster recovery assistance.

As a result of this 45-day storm, there is more than $400 billion in property damage and an additional $325 billion in business interruption losses.

No more than $30 billion is recoverable through private or public insurance.

When the waters recede, more than 170 California cities and towns are insolvent, unable to cover the costs of the services they required and hamstrung by drastically reduced property and income tax collections.

Deaths number in the thousands.

The state’s agricultural economy, once the biggest in the world and already damaged by years of drought, teeters on collapse.

Goodbye Disneyland. Goodbye Rodeo Drive.

The Modeling

What we describe is no apocalyptic fantasy. Rain and wind in these amounts came to California in December of 1861 and didn’t leave until the following February.

Geologists studying ocean sedimentation off of the coast of California determined that atmospheric rivers have dropped this much rain on California — or more — on at least six occasions.

The most muscular academic research in this area of catastrophe modeling is that done by the U.S. Geologic Survey’s Multi-Hazard Demonstration Project (MHDP), a multi-discipline effort involving more than 100 scientists, consultants and public sector officials.

As we described above, the ARkStorm that the project modeled in 2010 would produce more than $700 billion in property and business interruption losses.

“All of these scenarios are scientifically plausible,” said Dale Cox, the project manager for the USGS Science Application for Risk Reduction, the successor organization of the MHDP. Cox co-founded the MHDP and oversaw the ARkStorm scenario.

“They are not worst case scenarios but they are in general low probability, extreme events. We’re trying to create them so that they will be accepted. If it’s too big, people are going to blow it off and nobody is going to do anything about it,” Cox said.

To create the ARkStorm scenario, the team of scientists under Cox’s direction took the science used for studying earthquake trench faults — looking at where offsets in the fault occurred with carbon dating — and applied that to the deltas and marshes of California’s coast line.

What they deduced from that geologic evidence is that atmospheric rivers — massive storms that collect huge amounts of water from the atmosphere over the Pacific and pour it on California — have occurred and could well occur again.

“The metaphor I like to use is that it’s like turning on a fire hose and pointing it at California and moving it up and down California’s coast line,” said Laurie Johnson of San Rafael, Calif.-based Laurie Johnson Consulting. She previously worked at Risk Management Solutions, the modeling firm.

Prasad Gunturi, the lead for North America-related CAT modeling research and evaluation at Willis Re, said a recent scientific report likened an atmospheric river to taking all of the water in the Amazon River and dumping it in California’s Central Valley.

For this project, Johnson focused on long-term recovery implications. Willis Re’s Gunturi pitched in on economic loss analysis.

“The whole purpose of loss modeling is to come up with a risk management strategy. So if we know what we know now, what could we do and what would be the best investment to make now,” Johnson said.

To model the amount of wind, storm surge and flooding that accompanies an ARkStorm, Cox’s team “stitched” together data from two separate storms: a winter storm that affected predominantly Southern California in 1969, and a 1986 storm that impacted predominantly Northern California.

The team also mapped, for the first time ever, what it would look like if the entire state flooded.

“The whole purpose of loss modeling is to come up with a risk management strategy. So if we know what we know now, what could we do and what would be the best investment to make now.” — Laurie Johnson, founder, Laurie Johnson Consulting

“The team had to build that from scratch,” Johnson said. “Team members worked with FEMA and the state department of water resources to develop a statewide hydrology model and figure out how flooding progressed across river systems and through time statewide,” Johnson said.

Legacies

Using trench analysis carbon dating to study California’s storm history is one of the project’s legacies.

Bringing the term ARkStorm into public consciousness is another. “It’s something you hear quite commonly now with the media and the weather media. Not because we did it, but … it was a new concept,” Johnson said.

The ARkStorm scenario also showed California’s emergency responders that they were going to have to look at flooding in a whole new way.

Here was a statewide event they had never considered before.

“Central California was once a large inland sea with very low elevations in many spots. I knew that from my geoscience background,” Johnson said.

“But I don’t think people appreciated that in 1861-1862, flooding basically closed the capital, Sacramento; the whole Central Valley became a lake for more than three months. It took more than three months to drain the city,” she said.

“Nobody had looked at the statewide flows,” Cox said.

“California has really good flood fighters. We have really good emergency responders. We are looking at a scenario that would challenge them and that is what we’re trying to do,” Cox said.

Since the ARkStorm report was produced, Cox and some of his teammates have taken its hydrology and meteorology science and applied it at local levels. They’ve presented an ARkStorm scenario to officials in Ventura County.

“It was a really eye-opening experience for them,” Cox said.

Cox has also produced a study, published in January, detailing what would happen to the Lake Tahoe community in the event of an ARkStorm.

Look at these two factors alone.

One: That community takes its drinking water out of Lake Tahoe, untreated for the most part.

Two: Tahoe’s sewage treatment facilities are mostly at lake level. Should an ARkStorm strike, pumping that sewage out of the basin would become impossible.

Also, take into account that the workers who operate those sewage plants live on the other side of the mountain ridges, in more modest communities.

The snow from an ARkStorm would stop them from getting to their jobs.

“We often talk about The Big One [a big earthquake on the San Andreas Fault]; this is a bigger event,” said Anne Wein, an operations research analyst with the U.S. Geological Survey based in Menlo Park, Calif.

“What struck me was the evacuation being similar in size to a hurricane. We forget that this can happen in California,” Wein said.

Additional 2015 Black Swan coverage:

To Clean Up a Dirty Fight

To Clean Up a Dirty Fight

A dirty bomb detonated in Manhattan could make a ghost town of the most populous city in the U.S.

The Darkness of the Sun

The Darkness of the Sun

A fast-moving geomagnetic storm blasts the North American power grid, leaving a large swath of the Northeastern U.S. temporarily uninhabitable.