Black Swans

To Clean Up a Dirty Fight

When explosions shook the Chernobyl nuclear power station in 1986, they released enough radioactive material into the environment to kill 30 workers within a few weeks of the incident due to acute radiation poisoning, and sicken at least 100 others.

Large areas of Belarus, Ukraine and Russia had to be evacuated due to high levels of contamination, displacing roughly 335,000 people. A 30-kilometer area around the reactor was completely closed off, and a square mile of contaminated pine forest was cut down and buried.

The explosion in this case was an accident, triggered primarily by the poor training of plant workers, but it demonstrated what kind of long-term damage can result from improper use of radioactive materials.

Before the reactor explosion, 14,000 people called Chernobyl home. The surrounding villages were erected mostly to house plant workers. The City of New York, by comparison, boasts 8.4 million residents and nearly 700 skyscrapers.

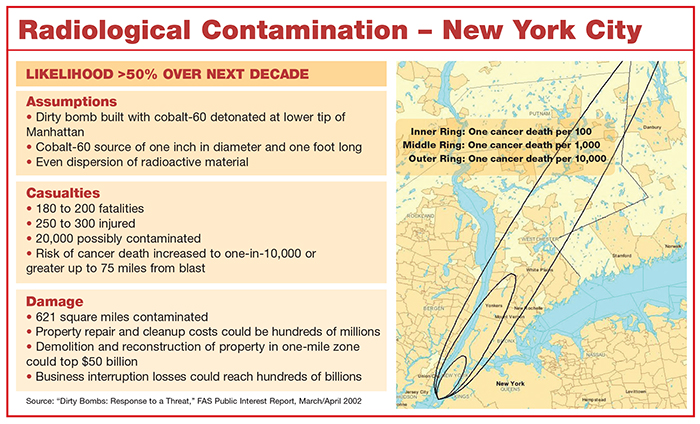

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) took a map of the radiological damage from Chernobyl and laid it over a map of New York City to demonstrate just how many properties, businesses and lives would be impacted by an explosion of radioactive material.

But the FAS scenario isn’t based on a nuclear power plant explosion; it’s based on the possibility of a terrorist “dirty bomb” attack. Dirty bombs, or radiological dispersion devices (RDDs), combine a conventional explosive with radioactive material, and concern is growing that they could be the next terrorist threat.

Research laboratories, food irradiation plants, oil drilling facilities and medical centers are just some examples of facilities that house radioactive elements like cobalt, cesium, plutonium and Americium. The small quantities that these facilities work with are protected as a commercially valuable asset, according to the FAS, but “once radioactive materials are no longer needed and costs of appropriate disposal are high, security measures become lax, and the likelihood of theft or abandonment increases.”

The Attack

The FAS focused its scenario on a dirty bomb built with cobalt-60, a radioactive material used in cancer treatment, industrial radiography, sterilization and food preservation. Facilities keep cobalt-60 in the form of small metal rods that are perfectly safe when encased inside therapy units or other machinery, but emit dangerous levels of radiation if the casings and rods are broken and particles of the cobalt-60 are dispersed.

The explosion of an RDD with cobalt-60 would send a cloud of radiation over a radius of at least several miles from the blast site.

“Based on the type, size and location of the device, we predict that in an urban environment, one building will need to be demolished, eight others will need repair, and about 75 more will need cleanup or decontamination,” said Hart Brown, vice president, organizational resilience, at HUB International.

“The physical nature of the damage will be localized, and small in comparison to the contamination aspect.”

A highly radioactive and powerful bomb could reasonably result in “180 to 200 fatalities, 250 to 300 injured, 20,000 possibly contaminated, and as many as 100,000 to 200,000 that think they could be contaminated,” Brown said.

Mark Lynch, head of terrorism model development on the impact forecasting team at Aon Benfield, estimated that radiation could spread over a 32-block radius from the blast site, which would cover roughly 49 square miles.

A 2003 report titled “Radiological Weapons: How Great is the Danger?” foresaw an even larger impact. This analysis, written for the U.S Department of Energy by George Malcom Moore, a former senior analyst in the Office of Nuclear Security at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), concluded that even a very small amount of cobalt-60, if dispersed evenly, has the capacity to contaminate 137 square miles.

That would cause millions of dollars’ worth of damage, so imagine what contamination of 621 square miles could do. That’s just what the FAS predicted in its scenario. The simulation surmised that if a tube of cobalt-60, about one inch in diameter and one foot long, were detonated and the particles dispersed from a bomb in lower Manhattan, it would contaminate an area of 621 square miles, or about 300 city blocks.

By EPA standards, lingering radiation from a source of this strength could increase the risk of dying from cancer to one-in-100 for anyone living in the borough of Manhattan.

Within 30 miles of the blast site, the risk remains high at one-in-1,000. Within 75 miles, the risk reduces to one-in-10,000.

In a presentation of these risks made to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2002, the FAS reported that EPA recommendations dictate decontamination or destruction within that 75-mile zone.

“Everybody agrees that not a lot of people will be killed, but not everybody agrees on the amount of property damage,” said Moore, the scientist in residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. “The big hazard from a dispersion device or a dirty bomb is not killing people, but contamination of property, which is an expensive proposition. You can create an extensive amount of economic loss by doing that.”

The Cleanup

Decontamination is no easy task. Removing the radioactive material would involve sandblasting the top layer off of everything, and repeating the process until radiation levels meet the EPA’s emergency standard, which is twice the normal background level.

(According to the EPA, low levels of radiation exist naturally in the environment at all times. Sources include cosmic radiation from space, radioactive minerals in the ground and radioactive gases like radon and thoron.)

“We’re talking taking the top layer off of sidewalks, off the outer side of buildings, off of all the furnishings inside those buildings,” HUB International’s Brown said. “It could be months to years to get everything cleaned up.”

“Most people who deal with radiation are surprised we haven’t yet had an incident of this type.” — George Malcom Moore, former senior analyst, Office of Nuclear Security at the International Atomic Energy Agency

The FAS suggested that decontamination alone may not be enough. In cases where the risk of cancer could not be reduced to one-in-10,000, total demolition may be necessary.

If all of the buildings within a 1.2 mile area in New York City had to be demolished and rebuilt, the cost could top $50 billion, according the organization’s report, “Dirty Bombs: Response to a Threat.”

Overall, “if such an event were to take place in a city like New York, it would result in losses of potentially trillions of dollars,” the report said.

Even greater than the costs of repair and cleanup, though, is the loss from business interruption.

It’s possible that an exclusionary zone would have to be established until radiation levels fell low enough. Businesses in that zone would be unable to function.

Even companies in the surrounding area would lose a major portion of their customer base; when buildings are able to reopen, it’s likely that former residents and employees will not return, fearing the long-term health effects of any lingering radiation.

Brown referred to this as “radio-phobia,” where people treat radiation exposure as a type of virus they can catch and transmit.

“The fear,” said Aon Benfield’s Lynch, “is usually significantly higher than the actual damage.”

While very high doses can cause acute radiation poisoning and even death, most people will not be physically affected, though fear among the general public persists.

Brown estimates that BI losses could fall anywhere in the range of tens to hundreds of billions.

The Likelihood

The likelihood of a radiological attack using a small amount of radiation occurring within the next decade “is probably greater than 50 percent,” Moore said. “Most people who deal with radiation are surprised we haven’t yet had an incident of this type.”

Many medical facilities have rods of cobalt-60 on site, and they are not always well-guarded.

Video: Authorities in Mexico recovered a stolen truck that has been transporting radioactive material, in this report from ITN News.

That leads to many of what the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) calls “orphaned sources,” or small volumes of radioactive material that are uncontrolled, lost, or in the possession of someone not licensed to own it.

The NRC reports that U.S. companies have lost track of nearly 1,500 radioactive sources within the country since 1996, and more than half were never recovered.

Incidents outside of the country have demonstrated how easily the wrong people can get their hands on a radiological device.

In 2013, in the Mexican town of Cardenas, for example, a couple of thieves stole a truck carrying iridium-192, which is used for cancer treatment, to a waste storage facility.

That source was eventually found, but not before six people were hospitalized for radiation exposure.

In the city of Goiania, Brazil, in 1985, a private radiotherapy institute relocated, but left behind some cesium-137.

Part of the institute was later demolished, which destroyed the protective casing around the cesium and led to contamination of the surrounding environment.

Ultimately, about 112,000 people were medically monitored, 249 were contaminated either internally or externally, and four died. It took three years to totally restore contaminated areas to livable conditions.

Response and Recovery

Coverage for any losses stemming from a dirty bomb attack could be difficult to find. In order for TRIA to kick in, the incident would have to be clearly defined as an act of terrorism, but “crime scene contamination makes it more difficult to collect and examine evidence,” Lynch said.

Without a declaration of terrorism by the Secretary of the Treasury and the Secretary of Homeland Security, the losses could be insurmountable for affected businesses to handle on their own.

“When you get into nuclear terrorism, there’s really no ability to predict that loss. It gets complex based on the coverage, and there are a lot of exclusions,” Brown said.

“The federal government would have to provide some economic stimulus, some funds, to prop up the city throughout this timeframe, which again could be years.”

It’s not known whether extremist groups such as ISIS are actively building RDDs, but mishaps like those in Mexico and Brazil and the growing list of orphaned sources make a dirty bomb a very real threat.

In 2012, 160 incidents of lost radioactive materials were reported to the IAEA, 17 of which involved some type of criminal activity.

The NRC and Department of Energy have since made more aggressive efforts to document and locate orphaned sources; here’s hoping they pay off.

Additional 2015 Black Swan coverage:

Welcome to the ARkStorm

Welcome to the ARkStorm

A 45-day superstorm floods California and dishes out economic catastrophe.

The Darkness of the Sun

The Darkness of the Sun

A fast-moving geomagnetic storm blasts the North American power grid, leaving a large swath of the Northeastern U.S. temporarily uninhabitable.