Third-Party Litigation Funding and Its Impact on Commercial Auto — Part One

Commercial auto is currently a troubled segment of the property and casualty insurance market.

Insurance companies have struggled to make a profit in recent years, and they continue to find it difficult to control skyrocketing claim costs. Poor underwriting results from 2014 to 2019 have led to significant rate increases. However, many industry experts are asking if the large rate increases since 2018 are sufficient to keep up with the explosion in claim costs.

Reinforcing this overall sentiment, AM Best placed a negative outlook on the commercial auto market in 2022, and Fitch Ratings Services said the somewhat favorable trend in 2021 and 2022 may be unsustainable in 2023 and beyond.

We agree with these assessments and believe that it will be difficult for commercial auto insurers to be profitable in the near future, for several reasons.

First, there has been an explosion in liability claim severity and the associated legal expenses (both have been growing at the about the same rate).

Stephanie Fox of Verisk said the average verdict for claims with verdicts over $1 million increased tenfold between 2010 and 2018. We believe that the presence of third-party litigation funders (TPLFs) is a significant factor contributing to these trends.

Second, today’s inflation rate is as high as it has been in 40 years. In addition to normal consumer price index (CPI) inflation, auto manufacturers and body shops continue to face supply chain shortages that impede their ability to obtain parts and repair vehicles.

Third, the trucking industry is encountering a shortage of drivers and is struggling to recruit new drivers to the profession.

This shortage has increased driver turnover and put further pressure on delivery schedules. Inexperienced and significantly older drivers account for a large part of the workforce, and historical experience shows these drivers tend to have a higher frequency of accidents.

Lastly, insurance companies are facing adverse development on prior years’ reserves and less reinsurance capacity.

All of these factors are having a negative impact on insurers’ bottom line.

High Commercial Auto Loss Ratios

It is well known within the insurance industry that commercial auto insurance companies have been struggling for the past decade.

Loss and defense and cost containment expense (DCCE) ratios for commercial auto liability (CAL) have been noticeably worse than the overall property and casualty industry loss ratios since 2012, as shown in Figure 1.

While the outlook for commercial auto has generally been pessimistic, perhaps one point of optimism is that the gap between the CAL and P&C loss ratios has reached its lowest point in nearly a decade, with a difference of 7.4% in 2021.

While the outlook for commercial auto has generally been pessimistic, perhaps one point of optimism is that the gap between the CAL and P&C loss ratios has reached its lowest point in nearly a decade, with a difference of 7.4% in 2021.

To get a better sense of where commercial auto is headed, we examined recently published company 10-Q filings for the largest commercial auto writers.

Progressive notes an increase in claim severity in its commercial auto business, which is partially offset by a higher average premium per vehicle due to rate increases.

Allstate also notes unfavorable reserve re-estimates for its commercial auto book. However, Allstate attributes this reserve development primarily to the shared economy business written in states that Allstate has exited.

Conversely, both Travelers and Old Republic show favorable loss development in their commercial auto books for recent accident years, as documented in their second-quarter 10-Q reports.

While these 10-Q statements seem to send mixed signals, it is promising to see favorable development for Travelers and Old Republic, which historically have had more long-haul trucking exposure in their books than have Progressive and Allstate.

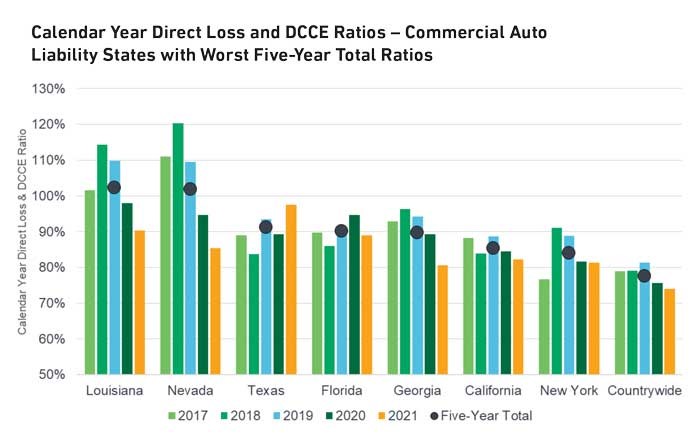

As Allstate alluded to in its 10-Q, loss experience has been noticeably worse in certain states, with six states seeing five-year loss and DCCE ratios above 85%.

Figure 2 shows five years of loss experience for the seven worst-performing states based on our analysis of industry data.

Various factors influence these results, such as the litigation environment, large trucking exposure and higher prevalence of nuclear verdicts.

Premium Growth Outpacing P&C Industry

Premium Growth Outpacing P&C Industry

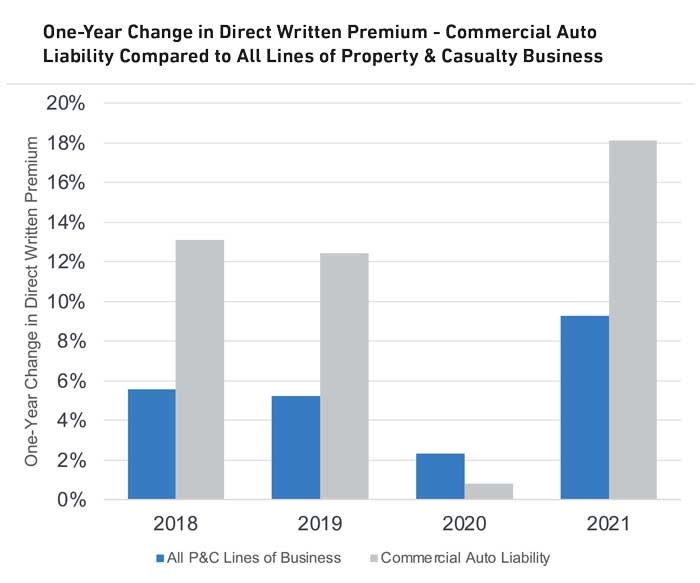

One might assume that the consistently observed adverse results would eventually be corrected as carriers take rate increases. In fact, commercial auto insurers have taken multiple rate increases during recent years, many even implementing large increases in back-to-back years.

Figure 3 shows that the one-year change in direct written premium has been roughly double that of the overall P&C industry in three of the past four years.

The smaller premium growth observed for commercial auto liability in 2020 is likely a function of reduced exposure, a reduced number of rate increases, and premium refunds or policyholder dividends due to the pandemic.

The smaller premium growth observed for commercial auto liability in 2020 is likely a function of reduced exposure, a reduced number of rate increases, and premium refunds or policyholder dividends due to the pandemic.

The impact of pandemic refunds and dividends is difficult to measure, given that their impact could be reflected in various accounting metrics including premium reductions, underwriting expenses or policyholder dividends.

The larger premium growth in 2021 seems to have made up for the reduced premium growth in 2020 as exposure returned to pre-pandemic levels and many carriers resumed (or continued) taking rate increases.

Background on Third-Party Litigation Funding

The rise in large verdicts on commercial auto cases is partially attributable to social inflation and the rise of third-party litigation financing.

Social inflation is typically described as a shift in claim costs due to the perception that some parties are better positioned to bear the cost of an accident. Many believe that social inflation is caused at least in part by a deteriorating sentiment toward big businesses after the 2007-2010 global financial crisis.

The public’s increased dislike for big businesses over the past decade is believed to be influencing juries looking for someone they perceive can afford to pay in the event of an accident resulting in a grievous injury.

Research by the Insurance Information Institute and the Casualty Actuarial Society indicated that, between 2010 and 2019, social inflation increased claims for commercial auto liability insurance by more than $20 billion.

The emergence of third-party litigation funders in recent years is also a significant factor that insurers must be aware of, given the potential impact on litigation costs, the resolution strategy, the insured’s potential exposure and, ultimately, the insurance industry’s bottom line. TPLFs provide upfront financing for often expensive and drawn-out litigation in return for a percentage of the proceeds from the case, if it’s successful. The TPLF sector has blossomed into a massive industry in recent years, and major players now invest billions of dollars annually in litigation.

TPLFs first emerged in personal injury actions and provided plaintiffs who could not afford a lawyer or find a lawyer to work on contingency with a way to “have their day in court.” However, many TPLFs no longer provide funding for personal injury actions. Instead, TPLFs have turned their focus toward commercial litigation and class actions in an effort to seek out much larger recoveries.

A major target of TPLFs in recent years has been the commercial auto industry.

What was once described as a business focused on assisting the Davids against the Goliaths — with the Goliaths defended by larger insurers — third-party litigation funding has rapidly expanded and turned that dynamic on its head. As a result, TPLFs have driven settlements up, along with litigation costs and awards, and the small plaintiffs are now on equal footing, if not in a superior position, to the Goliaths.

The TPLF phenomenon is somewhat amorphous because TPLFs often hide in the background, and defendants are often not even aware that a third party is financing a plaintiff’s case.

TPLFs generally agree to fund litigation costs and expenses with no guarantee that they will receive a return on their investment. Interestingly, most TPLFs were founded by and continue to be controlled by former litigators who left the courtroom for a boardroom. Prior to investing in a case, TPLFs must weigh the cost of litigation against the expected award or settlement. Ultimately, any proceeds are used to pay the attorney fees first, and then TPLFs take a large portion of the recovery, often leaving the plaintiff with less than half of the settlement or award.

At the same time, some of these cases would never have been brought to trial without the TPLF involved, because a plaintiff’s attorney might not be willing to assume all the risk (and significant cost) of taking the case. Thus TPLFs’ assumption of the litigation risk generally increases the amount of litigation. And increased litigation — both the number of lawsuits filed and the increased length of the case — is impacting insurance companies, as well as the entire court system.

So what is the TPLFs’ influence on the bottom line? Find out in Part 2, as these actuaries from Milliman dive deeper into commercial auto and third-party litigation funding. &