The Trials and Triumphs of Workplace Injury: 3 Lessons This Workers’ Comp Professional Learned After Shattering Her Leg While on the Job

Michelle Despres, vice president of product management and national clinical leader for physical therapy at One Call, has had a rough start to 2022.

While attending the annual American Physical Therapy Association’s conference, held February 2-5 this year, she broke her leg walking across the crosswalk toward the conference center in San Antonio.

“I remember telling myself, ‘It could be slippery. Be super careful.’ But outside, the streets just looked wet,” she noted of the wintry weather conditions that fated February morning.

Still, she slipped and fell, resulting in a spiral fracture of her tibia with comminuted fractures of the tibia and fibula bones. In part one of this two-part series, Despres shared her story, from day one of her injury through her weeks of recovery.

“I had two surgeries in two cities. I’ve gotten 14 incisions, and I was hospitalized for nine days,” said Despres, who has 24 years of experience as a physical therapist in the workers’ comp space.

Throughout her recovery, Despres has had the oppotunity to reflect on her workers’ compensation journey. Below, she shares the top lessons she’s learned throughout her harrowing experience.

1) Injured worker advocacy is more than just lip service.

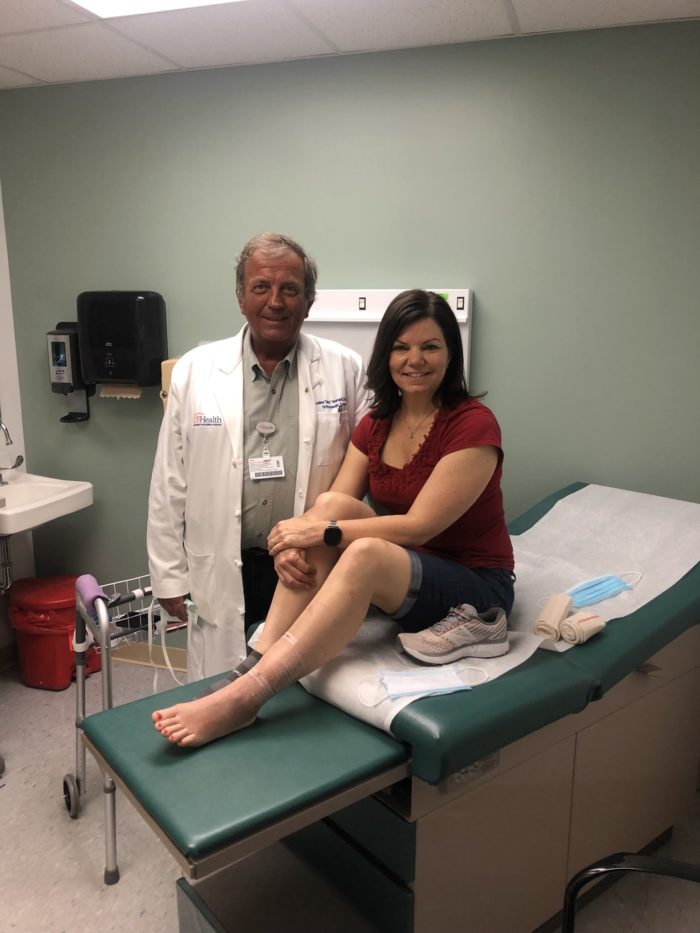

Despres weeks into her recovery with her doctor.

Despres faced several challenges during her initial intake at a hospital in San Antonio, most importantly around where she would spend her time healing. A Jacksonville, Fla. resident, Despres couldn’t spend the 12-week recovery period away from her home and support system.

She spent countless hours on the phone trying to get back to a familiar place to heal.

“Getting injured in a city that was not my home created unique problems, and the care coordination from the San Antonio team was lacking,” Despres said. “I was pushed to make medical decisions quickly and alone. The physician did not suggest a viable plan, and the hospital case manager was not willing to find a better solution.”

She said it felt like the hospital team checked the boxes and left early for the day. She added she was lucky, because she and her husband had a friend who was a surgeon in Jacksonville. He was able to help facilitate a hospital-to-hospital transfer and streamline next steps, which included the final surgery that occurred a day after traveling via air ambulance to Jacksonville.

But most injured workers are entering the workers’ compensation system for the first time and don’t have the same knowledge.

Sometimes, Despres added, they might think they have the right advocacy, but they don’t. “For me, I had a hospital case manager. It’s her job is to make sure things are done right,” she stated. Unfortunately, the case manager left Despres feeling disappointed. Even something as minor as trying to get pain management medication or even a muscle relaxer at night was a challenge.

Despres had to fight for her own voice to be heard, but that shouldn’t be the case in this industry.

2) Psychosocial components really do matter.

While dealing with a shattered bone, Despres had to figure out where to go and how to get there without much help from the San Antonio-based hospital team.

The logistics of her injury — being in a different city, waiting for her husband to join her (hampered by flight delays/cancelations), having to make quick decisions about her care while also in pain — made for a mountain of stress that weighed on her.

Once Despres was back in her own home, she noticed other components of the biopsychosocial model at play during her road to recovery.

“My husband owns a business. He is not able to be a full-time caregiver and run his business,” she said. “It’s a challenging situation. We’ve always shared housekeeping responsibilities — the laundry, meals and house cleaning. Now, he’s doing all of that, and I’m doing very little. It’s stressful for him and frustrating for both of us.”

Despres unexpectedly lost her mother last year, as well, and the grief is still raw. Even though her physical injury requires time and attention, the emotional wounds from the loss of her mother require time too.

Further, she’s an active person. “I’m a hiker, a runner, a cyclist, and a dancer — all things not currently possible because of my injury,” she said. She was very concerned about her ability to resume these activities, but first, she had to learn to walk again.

At home, she and her husband had to pause several ongoing renovation projects, leaving her personal space in a bit of disarray with no clear resolution date. She’s now at the point where she can use a short-rolling stool to do laundry and work on floor-level projects again.

“Significant injuries create numerous small and large challenges,” she said of the key lesson the industry should take from her experience. “It’s frustrating having to depend on others. The earlier independence is achieved, the better. Sometimes, that independence is measured via small victories.”

For her, a small victory was being able to put on her pants by herself — an everyday task we take for granted until we can’t do it anymore.

3) Collaboration and expertise are key.

During her stint in San Antonio, Despres quickly learned there was a gap in the workers’ comp system when it came to the information being provided by health care folks who should be workers’ comp experts.

Autumn Demberger was ‘highly commended’ for her reporting by the Willis Towers Watson 2023 Journalist of the Year award in the “Insurance & Risk Profile Interview of the Year.” Reporting for this article contributed to her recognition.

“If you work at an orthopedic practice and your title is workers’ compensation coordinator, you should have a solid understanding of your physicians and workers’ comp regulations. You should not be telling people incorrect information. Lacking knowledge of basic aspects can derail the solution,” she said.

Her real-life example came in the form of a phone call with a Jacksonville-based surgeon’s office where the woman on the phone told her Florida workers’ comp law states she couldn’t be treated for 90 days post-injury.

As someone who works in this industry, Despres knew that information was wrong; however, she is the exception because she works in workers’ comp. Injured workers who are told this are likely to believe it instead of question it.

Despres experienced additional hurdles in the workers’ compensation process.

The pharmacy failed to accept the field case manager’s authorization, and it took numerous phone calls to get her medication filled the next day. In addition, a supplier initially refused to fill the order for her bone stimulator, stating they did not have a prescription. After sending the request up the supervisory chain, Despres discovered they only had one page of the two-page DWC-25 form needed to fill the order, an issue that could have been resolved much earlier in the process.

“There were a few times when alignment was not present. Given I understand the industry, it wasn’t the worst thing that could happen. But someone who’s not familiar with the work comp system is not going to know,” she said.

“They’re going to assume whatever someone says or does is the right thing, and that may not always be the case. Collaboration and communication amongst all stakeholders matters.”

Other Takeaways for the Workers’ Comp Industry

An avid runner pre-injury, Despres didn’t let a broken bone stop her from joining her family for the 2022 Gate River Run 15K.

While Despres has had obstacles to overcome, she has also had the opportunity to reflect on all the things that have gone well.

“Early engagement — the importance of starting care early — is something I talk about often, but now I’ve lived it,” she said. “This experience confirmed for me that those first steps are so critical. The last steps matter, but the first steps matter even more.”

The support from her adjuster, telephonic case managers, employer and co-workers enabled an early return-to-work and a sense of normalcy.

In fact, Official Disability Guidelines lists anticipated return-to-work best practices as 51 days, but the average is approximately 115 days. Despres was able to return by day 18. On day 74, her physician cleared her for plane travel. This approval removed all restrictions from her work ability and put her one step closer to independence.

Workers’ comp is excelling in its use of technology.

“Texting in response to DME requests was fast and easy. We can text any time, from anywhere. That’s not always the case with phone calls,” she said.

Constant communication puts injured workers at ease. Despres’ adjuster worked hard to keep her informed, and her telephonic nurse case manager helped guide the process and identify areas that needed to be addressed.

This ultimately helped Despres feel in control of her own recovery and provided much-needed peace of mind.

Throughout the ups and downs, if there’s one thing Despres wants the industry to remember, it’s this: Injured workers have very little understanding of the system and what to expect.

“They need our guidance, advocacy and expertise. It could be the difference between a successful recovery journey or one that leads to less desirable and costly outcomes.” &

A Workers’ Comp Professional’s Harrowing Journey Through the Workers’ Comp System

A Workers’ Comp Professional’s Harrowing Journey Through the Workers’ Comp System

Missed part one? See how Michelle Despres of One Call broke her leg while on the job and what happened as she entered the workers’ comp space as a patient for the first time.