Marine Risks

Supersized Risks

If any proclamation were needed to confirm that the day of the mega cargo ship has arrived, just look to the notoriously penurious Port Authority of New York and New Jersey spending $1.3 billion to raise the deck of the Bayonne Bridge.

The roadway will be raised 64 feet, to 215 feet above mean sea level with a target completion by the end of next year to allow the new monster container ships access to the sprawling port facilities in New Jersey.

Megaships are not new, but construction and use are definitely trending up — as is a rise in incidents.

With the coming of the megaships, “the newer tonnage Panamax [300 meters] ships are being moved on to runs that were traditionally considered feeder runs. This means larger vessels in smaller ports. The result is less room for error,” said Capt. Andrew Kinsey, senior marine risk consultant with Allianz Risk Consultants.

“We [already] see a rise in incidents with these size vessels,” he said, noting that “the mega container ships are more likely to encounter incidents during arrival and departure in near coastal or port areas due to the fact that there are fewer ports that accommodate these ships.”

“As a result, the most devastating scenario will involve two of these vessels in a collision situation during arrival or departure. The channel gets very crowded when you have one or two of these maneuvering.”

Construction Trends

Visionary naval engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel built the 700-foot-long S.S. Great Eastern in London in 1858.

In recent decades, ultra-large crude carriers, or supertankers, have ranged up to 1,500-feet long and 250,000 deadweight tons (DWT). Mostly single-skinned, the majority has been scrapped or retired as floating storage platforms in favor of safer double-hulled tankers.

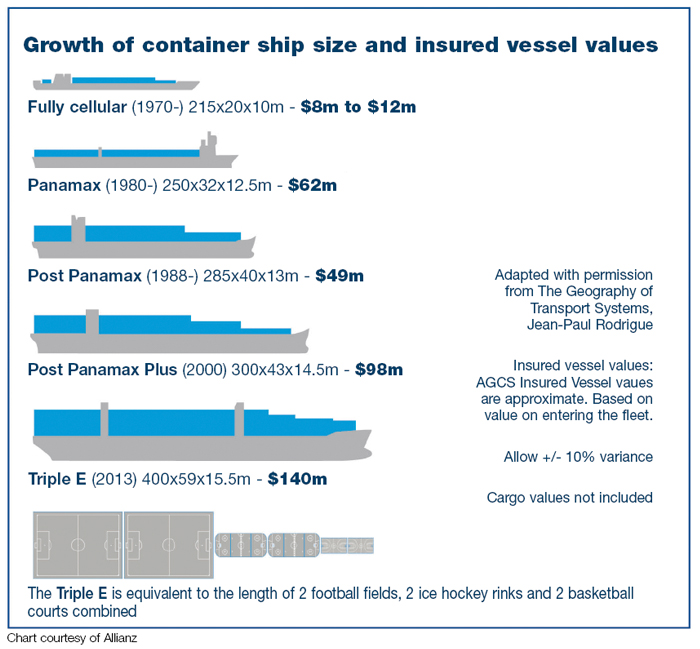

The latest mega container ships, the Triple-E class, will rival supertankers at 1,300-feet long. Costing $200 million each to build, the Triple-E class will have 18,400 TEUs (the common measure of box container capacity) — the capacity of 18,000 20-foot equivalent units. Standard shipping containers today are 40-feet long.

“The container ships of 18,000 TEUs and greater will have a trickle-down effect that is already being felt,” Kinsey said.

From the perspective of the underwriter insuring the hull and machinery, he said, “the stresses that these vessels are subject to are exponentially increasing as the size increases.”

“If we look at the failure of the MOL Comfort [built in 2007, 316 meters in length, 8,100 TEU capacity, which broke in half off Yemen in June 2013], we see a relatively new vessel built by a quality yard suffering a catastrophic failure; directly attributable to the lack of adequate container weights being provided to the vessel so that the ship can accurately calculate its trim and stability profile for the voyage.

“Couple this with the increase in fuel costs and the pressures to reduce the amount of ballast being carried and you have vessels that are running very high bending and shear force numbers. And actually, these numbers are based on faulty data because the actual container weight is not known,” he said. “Over time, this leads to premature failure of the hull structure.”

Published accounts indicate the MOL Comfort hull and machinery were insured for $66 million. The total loss cost underwriters between $300 million and $400 million in claims.

The “firmly entrenched [trend of] super-slow steaming” is another factor compounding megaship stresses, Kinsey said.

“The container ships today on the transpacific route are steaming at the same speeds as the clipper ships did. This is a cost savings measure that is here to stay with the new Triple-E class vessels having engines designed for these slower steaming speeds.

“This leads to greater exposures to controlled atmosphere cargo containers and an increase in losses, because these larger ships also need to use feeder ports. So we are looking at increased steaming time, more exposure of the reefer box to mishandling during transhipment and a subsequent increase in [cargo] losses.”

No Special Conditions

For underwriters, “hull and machinery coverage for ships is pretty much standard, tailor-made to the insured’s trade and operations,” said Sven Gerhard, global head of marine hull and liabilities at Allianz.

“There are no special policies or special conditions for megaships. Terms and conditions for a client might reflect the size of ships, for example, by higher deductibles and the insured’s self-retentions for larger vessels.

“There are no fees charged,” he said. “Premiums are driven by multiple factors, including type and size of tonnage, but also deductibles, fleet size, the quality of the insured’s risk management and the past loss experience have an influence on rates.

“This is why it’s very difficult to determine whether a rate change is determined solely by vessel size. It’s, for sure, a fact and probably not a surprise that due to values at stake, such vessels usually pay higher effective premiums than smaller vessels of the same type.”

That is corroborated by brokers.

“For bigger vessels, the premiums are generally higher,” said Robert Waterson, senior vice president of marine at Lockton in London.

That is not so much a deliberate decision by underwriters; rather, it is simply a function of arithmetic, he said.

“There are two aspects to the risk transfer equation for a vessel. One is the risk of total loss, which is easy. The value of the vessel determines the premium.

“The other aspect is the risk of partial loss from any cause. That is highly variable, but the accepted calculation is based on the tonnage. So you can see, larger vessels will pay a higher premium,” he said.

Waterson also confirmed that Lockton “is certainly working with owners who are ordering larger and larger vessels, especially ‘Cape-size’ bulkers.” Too large for any canal, they have to travel around the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn.

“There are bigger earnings for bigger vessels,” he said.

That is especially true of cruise ships. “We have worked with ships worth $1.4 billion,” said Waterson.

“The biggest problem with those is not overall capacity in the market, but rounding up enough subscribing underwriters. Each one takes $5 million to $10 million. It is a big challenge for the broker to line up the slip for $1.4 billion.”

While sinkings garner most of the attention, partial losses are more common. But even in those situations, the megaships present new challenges, said Martin McCluney, manager of hull and liability and U.S. marine practice leader for Marsh in New York.

Now instead of 2,000 to 3,000 containers to be salvaged, it could be 7,000 to 8,000 — all with different owners, he said.

To put that into perspective, the M.V. Rena, which grounded off New Zealand in 2011 and disintegrated in dramatic slow motion over two weeks, carried just 1,300 containers.

“The Rena was a modest sized ship,” said McCluney. “And the New Zealand government was adamant that as much cargo and fuel be removed, and then the wreck salvaged. In decades past, such a wreck would just have been left to the sea.

“The claim ran to several hundred million dollars. With the megaships, you are looking at about five times the Rena’s capacity. What would that take in time and equipment to salvage?”

Still, McCluney said, the most important factors to underwriters are not the size of the vessel, but the financial stability of the owner, the maintenance of the vessel and the training of the crew.

“You could have a brand-new ship, and if it is run shabbily, size won’t matter,” he said.

McCluney noted that the commercial drivers behind megaships are no different from sprawling malls, factories, or subdivisions. The only difference is that malls don’t sink.

“Insurance for ships is not really driven by size,” he said. “Still, the P&I clubs have awakened to the reality that removal-of-wreck costs do increase substantially with a much larger vessel.”

In such cases, environmental regulations could drive coverage costs higher, but as the rules differ around the world, and as the megaships are still new, there is no sense in the market how that will play out.

Some suggest that if the ships operate several years without major incidents, underwriters may calculate that catastrophic risks are low for the megaships as a class. If there are some losses, and operators balk at higher premiums, then bonds or some other alternate method may be devised for megaships.

“So far the bigger ships don’t rate as more exposed,” said Waterson at Lockton.

“We have not seen anything about them that indicates they are inherently riskier. But we are all still just feeling our way. There has been nothing to come along yet to indicate anything to worry about. If there are a few losses, and it becomes clear that they were something related to the size, that would change the rating system.”

Training and support for the crew are essential, said Bruce Paulsen, litigation partner with Seward & Kissel in New York.

“Most of the first-class operators train and treat their crews well. But it is still a hard and lonely existence for the dozen or two people on these ships. There are also substandard operators in the world, but they don’t come to the U.S. You could not bring a rust bucket without certification and insurance into Port Elizabeth [N.J.]. The Coast Guard would not let you in,” he said.

But while casualties tend to be fewer, they are bigger — such as Comfort, Rena, Costa Concordia, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, and the recent Korean ferry disaster, Paulsen said.

“With the megaships, there is only a marginal increase in risk. They are more difficult to navigate, and they present more windage. They require taller and wider cranes, and not every port can handle them,” he said. “If there is a grounding or a collision, there is more cargo and fuel to try to salvage.

“But from a risk-management perspective, the shipping industry has done a very good job.”