Liability Risk

Sharing Risk

Uber, Lyft, Airbnb and Homeaway — we’ve probably used at least one, if not all, of these ride sharing or hosting services at some point in the last year.

For the customer, they are easy to use and often cheaper than using a taxi or staying in a hotel, and they’re flexible income boosters for the people providing the services.

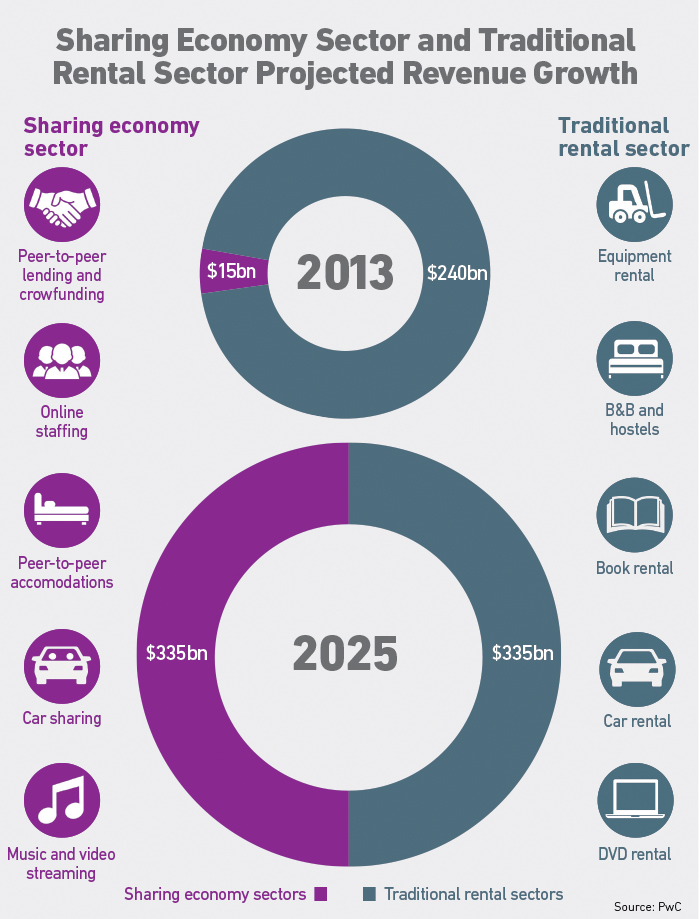

Given these immediate benefits, it’s no wonder that the sharing economy is booming, with PwC estimating that the industry will grow from $15 billion in 2013 to $335 billion by 2025.

However, despite its eye-popping growth, the sector faces a near-daily raft of legal and regulatory challenges that it will have to overcome. Those challenges include terms of insurance requirements, equal access and employment laws, zoning regulations, and health and safety standards.

There have also been a host of recent liability claims and lawsuits arising from high profile incidents, including reports of pedestrian deaths, rapes of home renters, invasion of privacy and bodily injury.

Among the most sensational allegations to hit the headlines are rented Airbnb properties ransacked by guests throwing wild parties and pedestrians hit and killed by distracted Uber drivers.

In many cases, the individuals who provide these services find out too late that they’re not covered by their insurance policies. That’s because their policies are not built for commercial use.

“The largest risk with the sharing economy is that you are now operating in a much more fluid environment,” said Michael Nelson, partner at Sutherland Asbill & Brennan’s New York office.

“The moment you decide to open up your business to a wider population, it creates a situation where more unknowns are likely to happen and therefore the legal liabilities are greater.”

Risks of the Sharing Economy

Melissa Neis, vice president at Parr Insurance Brokerage, said that risks exist throughout the sharing economy, from the platform itself, such as Airbnb or Uber, to the hosts or drivers who provide services, through to the end customer, and ultimately the wider community.

She said that the platforms often faced the biggest liability of having to thoroughly screen and, where necessary, train the individuals who provide services.

On top of that, she said, the hosts who rent out their properties through the likes of Airbnb and Homeaway are exposed to a host of privacy issues if they have unscreened guests with access to communal areas in the homes where they are staying.

“Because it’s such an emerging market and a new model, there isn’t necessarily the legislation or regulation in every country yet to be able to manage these risks,” she said.

Randy Nornes, executive vice president at Aon Risk Solutions, said that, given their global brands, the greatest risk for the platforms is protecting their reputation.

“When things go wrong you hear a lot of stories, particularly about the hosting services because there are millions of people renting out their homes everyday, whereas the transportation ones tend to be more sensational because they are fewer and far between,” he said.

“With these big companies, that can be reputationally damaging for them, so it’s important that they weed out any potential problems and have a proper complaint procedure in place for dealing with them from the outset.”

“What they can’t control is the exposures they face — it’s not as if they can go out and survey each and every home or check and see the quality of maintenance on a particular vehicle.” — Eric Silverstein, SVP, Willis Towers Watson

Howard Mills, Deloitte’s global insurance regulatory leader, said the biggest challenge for insurers operating in the sharing economy is underwriting and pricing for a completely different risk profile than the policy’s original intended use.

In the case of ride sharing, he said, a driver’s risk profile can change dramatically from the moment they go from driving their own car to when they activate the platform’s app before picking up a fare, to when they actually pick up that fare.

As a result of these changes in vehicle use, he said, policies can jump in price by as much as 25 percent to 30 percent.

“Say you have a standard auto insurance policy and you then decide to become a livery driver, that changes your risk profile significantly,” he said.

“Or in the case of a traditional homeowner’s policy, you decide you are going to rent out your home, or in effect become a mini-hotel. The insurer has no idea as to your risk profile and the people who might be occupying your home.”

Kate Sampson, managing director at Marsh in San Francisco, developed the first ride sharing insurance program for Lyft. She said that an added problem for many of the transportation network platforms is that they entered into the market knowing that there was a lot of ambiguity around the insurance contracts available in the U.S. and the different state insurance requirements.

“As an insurance broker, we have had to look at what was available to them in terms of insurance and how to overlay a product that would protect both the drivers and the general public,” said Sampson.

Lack of Insurance Coverage

Neis said that there is a general lack of understanding by the insurance industry about many of these platforms’ exposures, as well as a lack of specific programs designed to cover them.

“It’s tough for these businesses to find an agent, let alone an insurance company that understands their exposures and has access to the markets that can address them,” she said.

“Generally the insurance programs that are out there are both cost prohibitive and don’t offer comprehensive coverage.”

Neis said that most homeowners’ or drivers’ insurance policies don’t protect sharing economy users against some of the potential commercial use risks they can face.

Most home insurance policies are only designed to cover the named insured and family who live at that address, and they exclude commercial and short-term rental use, she said. Similarly, auto insurance typically excludes commercial and livery use.

“That might not be something that the service provider necessarily understands when they start to engage with these sharing economy businesses,” Neis said.

And while the likes of Airbnb and Uber have developed insurance programs for their service providers — Airbnb offers free primary coverage for liability for up to $1 million per incident — she said that many companies don’t have the wherewithal to offer their contractors a comprehensive policy.

On the insurers’ part, she said that while the sharing economy presented a big growth opportunity, many were wary of entering that market given the number of high profile court cases and the lack of regulation and legislation, not to mention the limited availability of terms and pricing data.

“It’s very common to hear from underwriters that they would rather compete for more traditional business rather than something more conceptual that is not as well established, as in the case of sharing economy companies,” she said.

Neis said that while endorsements may be written into some auto insurance programs to include commercial use, there is less development of programs on the home-sharing side because it is less profitable.

“When it comes to building some of the larger programs, I’m only aware of one or two underwriters at Lloyd’s of London that are actually looking at these types of businesses,” she said.

“The companies are probably not going to get the insurance coverage that they would like from the outset, so they may have to just settle for some form of cover in the meantime and build up a positive loss history that enables them to then work toward a more bespoke program.”

Risk Mitigation Techniques

Mills said that some companies such as Uber and Airbnb have responded to these risks by developing their own registry to block badly behaved or abusive customers from using the services.

Sampson added that the platforms are also running background checks on drivers, as well as using ratings systems for both the service providers and the customers that use them in order to gather feedback and provide them with a score.

“Many of these companies have screening processes in place and provide some form of insurance,” said Eric Silverstein, senior vice president of the national casualty broking practice at Willis Towers Watson.

“However, what they can’t control is the exposures they face — it’s not as if they can go out and survey each and every home or check and see the quality of maintenance on a particular vehicle.”

Mills said that despite their initial reluctance, more insurers have woken up to the shift toward the use of the sharing economy and the significant role they can play in its development.

“They need to embrace it and to be part of it so that ultimately they will innovate, get better on pricing and develop more products,” he said.

“The insurance industry therefore has to redesign its whole business practice to get to products and services that meet the needs of this new peer-to-peer economy and to provide a better customer experience that goes beyond just pricing.”