Return To Work

Protecting The Boom

Progressive return-to-work programs can help risk managers lower injury claims costs and keep older workers productive.

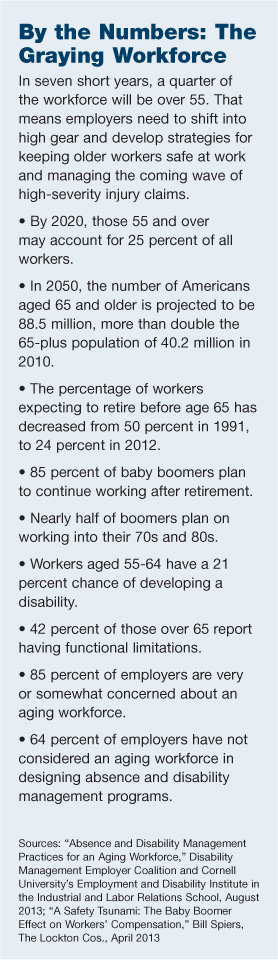

Nearly three years ago, the first of approximately 79 million baby boomers reached the age of 65. But faced with a still-shaky economy and shriveled savings and 401(k)s, many are choosing to delay retirement, to age 70 and perhaps beyond.

That’s good news to operations leaders worried about a mass exodus of skilled and experienced personnel. But it has brought the dawn of a new risk management challenge, as employers watch profits get washed away by the emerging tidal wave of costs associated with injured older workers.

Projected forward, the picture looks gray for employers. By 2030, almost one out of every five Americans will be 65 or older. Of the baby boomers about to reach retirement age, 85 percent plan to keep working past retirement age — most of them on a full-time basis.

If you look at the baby boomer population on a graph of the total population, said Bill Spiers, vice president and Risk Control Services manager for Lockton’s southeast region, “it looks like a big wave.” Spiers said that wave represented more of a tsunami — hence the title of his recent white paper, A Safety Tsunami: The Baby Boomer Effect on Workers’ Compensation.

“I really believe it’s something that’s coming and I’m trying to be Paul Revere,” he said.

Heeding Spiers’ warning means developing strategies for managing the claims of injured older workers. Employers need to have plans in place and they need them now.

Realities of Age

The underlying problem is not that older workers are getting hurt more often. Being older and wiser, they’re actually getting hurt less than some of their less experienced counterparts. But when they do get hurt, their injuries are generally more severe, and take longer to bounce back from — a lot longer in some cases.

Patrick Walsh, chief claims officer and vice president of Accident Fund Holdings Inc., in Milwaukee, said that his team has invested some time drilling down into their data to find out more about older workers’ injuries. They found that while claimants over 55 didn’t have statistically more injuries than their younger counterparts, they did have a higher incidence of slip and fall injuries.

“At age 55 or older, around 33 percent of all claims are slip and fall claims and they’re expensive,” said Walsh, “approximately 25 percent more expensive than a standard strain or cut or puncture-type claim.”

Compounding these challenges is the aging process itself and all of its various and sundry baggage, from diabetes to heart disease to degenerative conditions — any of which can become obstacles to recovery from the mid-40s onward. These comorbid conditions can send claims costs skyrocketing, depending upon how a state’s law is structured.

For example, said Mark Walls, senior vice president, Workers’ Compensation Market Research leader at Marsh in St. Louis, you could have a situation where a worker had a preexisting but latent degenerative condition, which is triggered by a work injury.

The employee could have been a ticking time bomb for years, but if a judge blames the work injury for setting it off, the employer could still be on the hook for both conditions.

“When you have an aging workforce, you tend to have more of these preexisting degenerative conditions,” said Walls. “That’s just basic human anatomy. The body breaks down.”

Those added risks are all the more reason to focus on bringing employees back to work quickly after an injury. No matter what the root cause of the illness or injury, employers need to understand that recovery time shouldn’t necessarily mean time off work.

Aging workers’ longer recovery times are where return-to-work (RTW) programs can make a dramatic difference, in terms of claims costs and duration, injury outcomes, and overall employee morale.

But not all RTW programs are created alike, and few have the flexibility to accommodate the unique needs of an injured older worker, experts said. “What we’re seeing is that there’s got to be some revisions in return-to-work policies,” said Paul Braun, managing director of casualty claims for Aon Global Risk Consulting in Los Angeles. “They need to be changed in order to support the aging workforce.” As an example, he said, RTW programs often will have time limits. So a policy might specify that it can only accommodate injured workers for a certain amount of time until they’re terminated.

“They need to take a look at that and make sure they’re accommodating the longer healing period it takes for older workers,” he said.

In more traditional RTW models, the injured worker’s doctor writes a list of work restrictions. The employer takes the list and tries to match it up with one of the company’s designated light-duty positions. If there’s no match, the employee stays off work until enough restrictions are lifted to find a light-duty match.

It’s time to change that model in favor of more progressive thinking, especially when faced with the longer recovery times, said Terri Rhodes, executive director of San Diego-based Disability Management Employer Coalition (DMEC). In August, DMEC published a paper, State of the Field: Absence and Disability Management Practices for an Aging Workforce.

Rhodes said that employers need to focus on injured workers’ abilities, rather than their restrictions. Often, that process starts with getting doctors to rethink the way they evaluate injured workers.

“I used to get all these restrictions [from doctors] and I’d go back to them and say, ‘Don’t tell me what they can’t do. Tell me what they can do.’ ” Without that guidance, said Rhodes, many physicians will default to what it is the patient is saying he or she can’t do.

From there, she said, accommodating an injured worker’s abilities is a matter of imagination and ingenuity. “Return to work is all about creativity,” she said. “I believe that a return-to-work program is only as good as the people managing it, and whether they are flexible and innovative in how they manage the return-to-work process and in looking at creative ways to get people back to work.”

Mike Milidonis, manager of Ergonomics and Employer Services at GENEX Services Inc., agrees with Rhodes’ assessment. “The most successful strategy is matching employees’ abilities with the job demands. The reason is that it takes out a lot of the gray area — it eliminates the question of if they can come back.”

Of course, if matching tasks to abilities was as simple as it sounds, everyone would already be doing it. The solution isn’t always obvious, and that’s where the creativity comes in. Start with a critical assessment of the employee’s pre-injury tasks and determine whether any of them could be done differently.http://www.vermontcaptive.com/about-us/why-vermont.html

“A lot of times we get tunnel vision,” said Milidonis. “And we get wrapped up in doing things the way we’ve always done them.” When you’re willing to embrace change, you’re more likely to spot solutions, he said, and sometimes the answer can be something as simple as changing a tool or a piece of equipment. “You change the tool, and maybe you eliminate the movement or posture that the doctor didn’t want [the injured worker] to do.”

Looking at another facet, it’s also important to factor in whether an older worker’s injury is causing fatigue or difficulty focusing. In some situations, RTW arrangements may require flexible scheduling, job sharing, telecommuting options or alternate work locations.

The German Models

The holy grail of RTW programs might be one that can simultaneously accommodate injured older workers while helping to keep other older workers from getting hurt in the first place. But in order to see such a thing in action, you’d have to travel to Dingolfing, Germany, 50 miles northeast of Munich, to a BMW production line. Six years ago, managers noticed that their workforce was aging, and were alarmed by the prospect of not having enough engineers and skilled workers to fill their shoes. So they set about creating a program to keep them safely at work for as long as possible.

What they built was a separate assembly line just for their aging staffers, with mechanical hoists and adjustable-height workbenches. Accommodations include a two-hour rotation cycle to reduce fatigue, wooden floors to help hips swivel more easily during repetitive tasks, and movable large-type instruction boards.

Lockton’s Spiers said the Dingolfing site is the only example he’s been able to find of a risk-control program targeted solely at the aging workforce. He said that all of BMW’s simple and inexpensive changes could have a powerful impact not just on injury prevention, but on the company’s ability to bring injured workers back sooner.

“If a job requires less [physical stress] because I’ve already automated it, it only makes sense that I might be able to bring someone back earlier,” reasoned Spiers.

BMW’s neighboring Audi plants have been facing a similar threat of talent loss, combined with physical impairments affecting nearly half the staff. Audi has adapted positions and designed custom workstations to accommodate even serious restrictions.

The company’s vision is to design a workplace where even wheelchair-bound employees would be able to do demanding jobs.

BMW, Audi and other German automakers are proactively trying to manage the so-called “brain drain” that many U.S. companies could be facing unless they put programs in place to help keep employees at work and engaged as they recover from injuries or illness, whether work-related or not.

“You want to protect this group of people,” said Spiers. “They are incredibly talented; they have a ton of knowledge about their job and about the workplace. When they go out with illnesses or injuries, returning them back to work is critical to a company’s ability to keep producing their product or service.

“It’s about workers’ comp and reducing costs,” he added, ” but it’s also about maximizing our aging group. They’re motivated to contribute. I haven’t found any evidence that older folks just want to go retire and sit in a rocking chair and spend 20 years looking out at their front yard. They want to stay engaged.