Caffeine in a Can

A Jolt of Product Liability

Mountain Dew is perhaps one of the original “energy drinks.” Ironically, the neon yellow elixir, loved by 14-year-olds for its ability to get them flying high on the change in their pockets, was originally created circa 1940 as a whiskey mixer.

Brothers Barney and Ally Hartman couldn’t find a mixer they liked enough in Knoxville, Tenn., so they invented their own. The name “Mountain Dew” itself is slang for moonshine — homemade whiskey to you and me. The original Mountain Dew slogan was “It’ll tickle yore innards!” — particularly if mixed with moonshine.

Energy drinks as we think of them now — in sleek aluminum cans or plastic shooters — haven’t been around as long as Mountain Dew. They’ve existed in Europe for 20 years, and nearly 15 years in the United States.

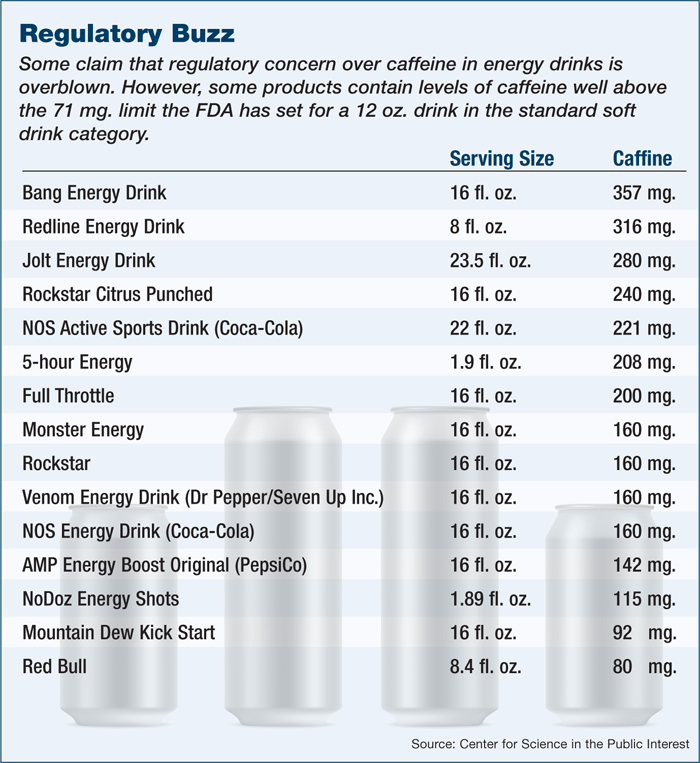

But today more than ever, they are in the white-hot public spotlight, accused of everything from encouraging the use of their products with alcohol to marketing to children to loading their products with unknown levels of caffeine and supplements — all of which appear to lead to emergency room visits and even the deaths of consumers.

In a way, energy drinks are suffering from their own success. The energy drink category grew at a double-digit rate in the fourth quarter of 2013 alone, according to Wells Fargo’s Beverage Buzz survey, cited in a convenience store trade magazine, and the market leader, Red Bull, saw $2.58 billion in sales in 2013, an increase of 8 percent over the previous year.

Sales come despite bad headlines and the target put on the industry by politicians such as U.S. Democratic Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois, who began calling for the FDA to investigate energy drinks after the 2012 death of a 14-year-old girl from Maryland, Anais Fournier. Lawmakers in Maryland are considering banning the sale of energy drinks to minors, while the city of San Francisco is suing the world’s second largest manufacturer, Monster Beverage Corp.

Are energy drinks as unique and dangerous as they’re made out to be? The answer is a bit yes and no.

“It all ties back to what is and what isn’t on the label of a beverage.” — Bernadette Heater, area assistant vice president, Arthur J. Gallagher & Co.

“All food and beverage products are facing increased regulatory scrutiny and the heightened threat of consumer litigation,” said Sarah L. Brew, the Minneapolis-based partner and food litigation and regulatory practice lead for law firm Faegre Baker Daniels. “But energy drinks are subject to even greater focus at the moment. … In that climate, the risk of recalls and product liability lawsuits is greater.”

In this particular context, Brew and other food and beverage experts prescribed a standard risk management recipe for energy drink manufacturers — of solid risk control, crisis management planning and understanding their insurance options.

Invigorated Risk Management

Labeling mistakes top the list as the most common product recall reason, according to multiple sources we spoke with, but they can be more complicated for energy drinks because the beverages can be classified as either a supplement or a food. Labeling requirements change depending on which category a beverage pours into.

The FDA re-emphasized the distinction between the two product categories in guideline reminders issued in January 2014 (in part in response to Sen. Durbin). In a two-part announcement, the FDA reminded energy drink manufacturers of the difference between supplements and foods, and its rules about adding substances to products.

As the FDA stated in these new guidelines, “It is your responsibility to ensure that substances added to foods you manufacture or distribute, including non-dietary ingredients in dietary supplements, comply with all applicable regulatory requirements for substances added to food.”

It stands to reason, then, risk management for energy drink manufacturers ought to begin with labeling and ensuring that a beverage is on the right side of these FDA guidelines.

“Typically, they have all come back to these issues,” said Bernadette Heater, area assistant vice president in San Francisco for Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. “It all ties back to what is and what isn’t on the label of a beverage.”

Energy drink manufacturers can turn to the American Beverage Association and its own voluntary three-step guideline, which includes openly revealing the total caffeine content of beverages (which is not mandated by the FDA); avoiding any promotion of mixing the drink with alcohol; and including a statement warning against consumption by children, pregnant and nursing women, and anyone sensitive to caffeine.

Brew concurs with much of it. About putting caffeine amounts on labels, she said:

“It may be a more difficult case for a consumer to claim they unknowingly consumed an excess amount of caffeine when the product label discloses caffeine content.

“Investing resources to ensure that labels are compliant and complete is money well spent,” she added.

Sound labeling or not, Heater said manufacturers ought to prepare for an “adverse media event” with a crisis management plan. Best-in-class ingredients for such a plan include: protocols to follow for responding to the media and government entities, communication plans for employees to explain what they should and should not say, and maintaining and documenting good loss control in the first place.

The market currently can offer several hundred million dollars in capacity on a per-risk basis for product recall insurance, but it’s not an inexpensive product. — Bernie Steves, managing director, national crisis management practice, Aon

In the case of food and beverage companies, proper loss control equals a HACCP plan, or Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points. Companies analyze and identify their critical control points, then determine how to manage then. Along the way, they document everything, continually reassess and amend as needed.

“Any food and beverage manufacturer has these plans,” Heater said, adding that energy drinks would not need to be treated differently within the HACCP framework.

Still, Heater said, many energy drink companies appear to be “four guys in a garage somewhere.” Such startups may not have the resources or personnel to handle HACCP, other safety and loss control issues, and regulatory and labeling requirements. In lieu of an expert on staff, Heater recommends founders at least do as much research as possible, particularly on FDA requirements, and bone up on HACCP too.

Besides the oft-repeated focus on labeling, Brew stressed that startups focus on the basics.

“Of course, producing a safe, quality product is every startup company’s goal. My advice is to prioritize investment in food safety and quality,” she said.

Recovery from Bad Press?

Michael Sachs, co-founder of nutritional beverage company CodeBlue was asked how his team handled risk management as a startup drink company. Lawyers? Consultants? In-house homework?

“It’s almost all of the above,” was his response.

As one might expect, Sachs said that labeling has been a major preoccupation since the company launched a half-decade ago. Initially, CodeBlue was brewed as a “recovery drink.” As a dietary supplement, its labeling required a so-called Supplement Facts panel (versus the Nutrition Facts panel that appears on food labels).

“Once you start putting supplements in there … you have to be very careful how much you put in, how you list them on the label … even vitamins and minerals,” Sachs said.

And although CodeBlue was not an energy drink per se, it got lumped in with energy drinks because of its list of supplement ingredients and especially because of its packaging — a slim, 12-ounce can. Whenever energy drinks suffered negative publicity, “it completely affected us,” Sachs recalled.

“Steel can means energy” in consumers’ minds, Sachs said.

The company then went through a transformation — expending considerable time and money to become a health drink. It changed packaging to a plastic bottle to disassociate CodeBlue from energy beverages. And the company revamped the recipe and switched to a Nutritional Facts label. To do so, it took out supplement-type ingredients like glutamine and NEC.

“Usually, if it’s a tough name to pronounce, it falls within the supplement category,” Sachs said about ingredients.

The government now finds all of CodeBlue’s ingredients to be “generally regarded as safe” — or GRAS.

The Insurance Recipe

As with any manufacturer of a product — whether that be a GRAS food product, a pharmaceutical or other consumable — the makers of energy drinks can derive protection for bodily damage claims from their general liability (GL) coverage, said Steven Pudell, the managing shareholder in Anderson Kill’s Newark office.

Pudell believes that energy drinks, however, may face similar high GL deductibles and self-insured retentions as do pharmaceutical firms, speaking to underwriters’ wariness of the products themselves.

“I think these energy drinks are the grandchildren of ephedra,” Pudell mused, referring to the supplement ingredient banned in 2004 by the FDA due to linkage to serious health concerns.

But the key coverage — again for labeling reasons — may be product recall coverage. Maybe.

Bernie Steves, the managing director for Aon’s national crisis management practice, responsible for the broker’s product recall and contamination insurance specialty business, said many recall policies would have exclusions if a recall was caused by an energy drink manufacturer being accused of mislabeling or failing to meet new FDA requirements. Deliberate mislabeling would also be excluded.

What it will cover is product contamination, providing payout for the costs of recall, loss of income and extra expenses to mitigate an event. Whereas GL policies may have a small sublimit for crisis management costs, contamination recall policies are “for the big loss,” Heater said.

The market currently can offer several hundred million dollars in capacity on a per-risk basis, said Steves. It is not an inexpensive product, though, and manufacturers ought to prove they have solid quality control and auditing procedures in place because, although competitive, underwriters took some hits in 2013 from the many recalls that occurred, from the horse meat scandal that rocked UK supermarkets and fast food chains, to Kellogg’s glass-tainted cereal, to U.S. frozen pizzas polluted with plastic.

An underwriter not familiar with a particular drink or its manufacturers may charge a higher rate, according to Heater. She mentioned one leading recall insurance market that declined to cover a new energy drink startup company because its management lacked experience in food manufacturing. Still, the basic belief on the market is that energy drinks are not necessarily more prone to recall or mislabeling issues.

“For the most part, we find that the rates are consistent with any other food or beverage,” she said.

This hopefully reassures the energy drink manufacturers out there who might feel persecuted at the moment.