Marine Risks

In Deep Water

On March 31, an explosion and fire on a Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) oil production platform in the Gulf of Campeche killed four workers and injured 16. The loss conjured images of the BP Macondo disaster off Louisiana in 2010, but there was no major spill this time.

Drilling rigs are owned by the service companies, but production assets on platforms and on the sea floor are owned by the oil companies. In very deep water, floating production, storage, and offloading vessels (FPSOs), often former oil tankers, are connected to multiple wells by flexible pipes and cables.

Subsea is a classic low-instance, high-loss market, underwriters say. Total claims on one incident can easily reach $1 billion. Nevertheless, it is a soft market, with capacity ample, competition keen, premiums low, and terms and conditions generous. In other markets such conditions usually lead some underwriters to reduce their participation or leave altogether, but that has not happened yet in subsea.

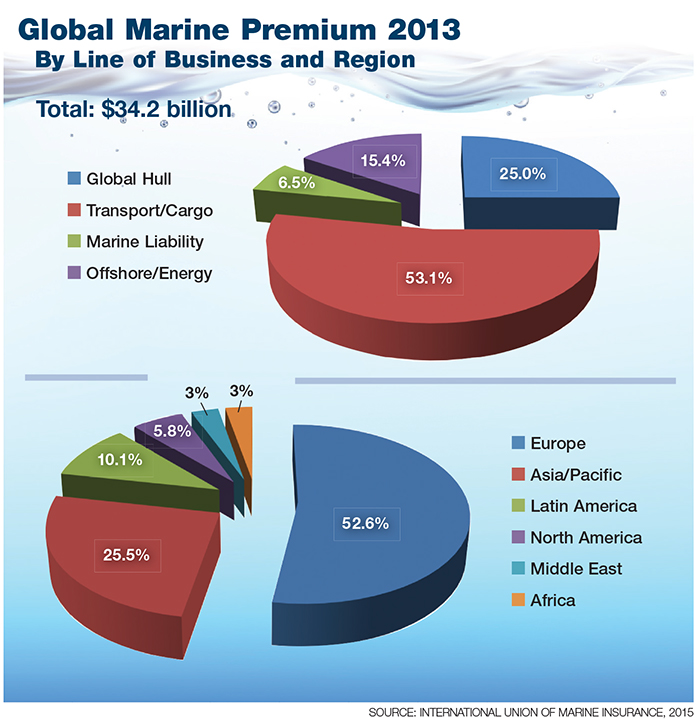

The global marine market overall is $34.2 billion, according to a recent presentation at the American Institute of Marine Underwriters (AIMU) by Dieter Berg, head of marine at Munich Re and president of the International Union of Marine Insurance (IUMI).

Drilling more deeply, global asset premium in the subsea market in 2014 was $5.1 billion, according to IUMI. Others put it closer to $3 billion, and anticipate that number will be about 25 percent less this year.

Underwriters say that reduction is driven by high capacity driving down rates, but also by the steep drop in the price of oil.

Energy industry sources confirm that capital budgets for exploration and expanded production have been sharply curtailed. As a result, there are fewer new projects and fewer new assets to be insured.

“There is a growing trend to move the more typical sub-surface activities to the sea floor — this, to potentially offset the costs in developing topside structures,” said Kashe Sambhi, head of energy offshore at Swiss Re Corporate Solutions (SRCS; “Swiss Re” as a stand-alone name is reserved for the reinsurance side of the shop).

“One very well-known mega subsea project is currently pushing the boundaries: The size of the asset would cover a football pitch. We would expect to see more of this in the future.”

He added that SRCS offers “proportional and non-proportional structures, with decent retentions and commensurate rating.”

Richard Palengat, head of energy and production at Lloyd’s syndicate Aegis London, noted that “conditions are as extreme as we have seen in 15 years. There is a certain stickiness. There is a lot of capital looking for a home, and quite a lot of it is new money. The insurance sector, especially property, is considered a good place to invest. That capital has not yet had the intelligence to pull out.

“It is often the case,” he said, “that some capacity has to wait until there is red ink on the carpet, and that may be the next thing.” The new money “may soon be disappointed that it is not getting the scale and the revenue it expected. What could bring an immediate change would be a massive loss. Or it could be death by a thousand cuts when claims exceed premiums.”

The Nature of the Beast

He said that while operators and underwriters work well together in risk management and loss prevention, the nature of the industry and its exposures mean that a series of claims or even a single large loss will consume several years’ worth of premium.

Another characteristic of subsea programs is that there is little layering. These are hugely expensive projects, undertaken by national oil companies, global majors, and consortia of operators and investors. They tend to have very high retentions and deductibles, and tend to go to just one or a select few commercial markets for the remainder.

Oil prices will not stay low forever, said Houston-based Peter Connors, global offshore leader for energy at Allianz.

“An awful lot of new capacity has come in at a down cycle in the energy sector. We hope we are seeing a bottom now because too many competitors are chasing too few insureds. But no one wants to leave the market.”

Connors noted that there have not been any major catastrophes, either rig losses or windstorms, though there have been claims related to repairs.

“We are already into the wind season in the Gulf of Mexico, and people who usually buy wind have been buying less — increasing their retention or just not buying.”

At the same time, Connors said that there is some opportunistic buying. “Some smaller guys are topping up their programs at lower rates. Those may be required to buy insurance from their lenders or investors.”

Allianz writes vessels while under construction, through load-out, towing, and commission. “Vessels” include floating rigs and platforms, as well as powered, navigable ships. All are under the jurisdiction of the marine classification societies. Equipment can be on board, fixed to the seabed, or suspended. Underwater assets have long been considered difficult to maintain or salvage, but Connors noted, “technology is getting better, so service and salvage have been improved.”

Technology is also enabling exploration and production in ultra-deep water, and in remote sites, from South America to Africa to New Guinea.

Even closer to established fields, development is stepping into deeper water farther away, and under harsher conditions. One example is the North Sea.

“The U.K. sector is older and in shallower water,” said Connors. “The Norwegian sector is newer, farther north, and in deeper water.”

Costs of equipment, maintenance, and replacement are magnified in deep water, said Frank Costa, president of Berkley Offshore Underwriting Managers, based in New York. He is also a member of the executive committee and former chairman of both AIMU and the IUMI.

“Subsea is a real challenge,” said Costa.

“In 10,000 feet of water, an anchor chain might cost $1 to $2 million, and just the act of inspecting can cost more millions, because it has to be done by remote-controlled submersibles. The anchoring and positioning systems of the floating structures is very complex.”

The emerging risk in this market is the deeper, more remote operations.

“In the North Sea, in the Gulf of Mexico, there is infrastructure and expertise in place,” said Costa.

“There are emergency and repair vessels. In remote areas, you may have to bring in assets from literally half a world away. So the reality is much more first loss. Deepwater repair costs can run ten times repair costs on shore. You get to total insured limits very quickly.”

Changing Exposures

The move to deeper water and more remote locations has been a significant shift in the risk profile, Costa said.

“What has happened to underwriters is that exposures have changed drastically. With fixed platforms a significant portion of the asset value was the concrete gravity base or the steel superstructure. Not much is going to go wrong with those.

For floating assets, they may not be as high value, but they are more vulnerable to loss. They are also more susceptible to wind and wave action.”

“The nightmare scenario is a catastrophic loss of one of these FPSOs off West Africa or in the South China Sea.” — Anonymous industry official.

The Gryphon FPSO, operating in the North Sea 175 miles northeast of Aberdeen, sustained damage in a storm in February 2011 when four anchor chains broke and the vessel moved off station, according to operator Maersk Oil.

That caused considerable damage to the subsea architecture requiring the Gryphon to be towed and dry docked in Rotterdam for repairs and upgrades. The claim was more than a billion dollars, according to underwriter estimates.

“That one claim really caught the eye of the reinsurance market,” said Costa. “It does not take a lot, just a couple of claims like that, seemingly small incidents that become high-profile claims.”

Despite that, multiple sources agreed that the subsea market remains accommodating. There are a few ultra-deep operations in remote locations that represent $8 billion to $10 billion in total asset value, but not all of that has been transferred to commercial markets. Still, a total loss for just one of those would represent a serious challenge to the market.

“The way to go about this is through a continuous dialogue with the insured to better understand their valuation methods,” said Sambhi at SRCS.

“Salvage costs will depend, inter alia, on availability of contractors, type of vessels, weather windows — thus, discussions with salvage companies to better understand their requirements is essential.

“Coordinating with loss adjusters and marine warranty surveyors to better understand risk and mitigation actions is also important. More relevant are the challenges of subsea repairs. These consist of more complex, higher cost equipment installed subsea in deeper and more remote environments.”

The less obvious but perhaps more substantive challenge is the proliferation of deep-water, remote projects of smaller scale. Energy industry sources confirm that most of the majors and national oil companies have ambitious plans for deep water, many of which are likely to move ahead once the price of oil recovers.

“The nightmare scenario is a catastrophic loss of one of these FPSOs off West Africa or in the South China Sea,” said one industry official.

“There would be few if any well-control or emergency-response vessels that could respond in a timely manner.”

SRCS has not noticed much change in loss trends that would move the market, according to Sambhi.

“We’ll see probably rises in specific loss-making accounts, though. Loss record for [construction all risk] has been decent, but there is still a fair amount of long-tail projects to be completed, thus there’s potential for deterioration in prior underwriting years notified later.”

On the risk-mitigation side, Sambhi added that underwriters and insureds are starting to work together mainly through industry associations and international bodies, such as IUMI and others.

“Marine warranty surveys help add some independent risk monitoring and improvement on some risks, but it’s not applied universally or in a consistent manner. The degree of open sharing, and dissemination of lessons learned across the industry, of incidents and near-misses between oil companies and contractors is quite low compared to the aviation or the downstream industries.

“Typically,” Sambhi said, “only lessons from high-profile, large losses are widely shared. There are also a few surveys produced and shared with underwriters. So, lots of room for improvement there.”