Employer Liability

Banning the Box

Deciding whether or not to ask job candidates on an application form if they have been convicted of a crime typically has been an easy call for employers.

By using that little job-application checkbox, the thinking was that employers are helping to protect existing employees from potential harm (and avoiding litigation if workplace violence does occur) and, at the same time, reducing enterprisewide risk (mainly in some form of theft).

Until recently, that decision was fairly easy because in every state except Hawaii the checkbox was perfectly legal (Hawaii passed a law banning it in 1998). In recent years, that has been changing.

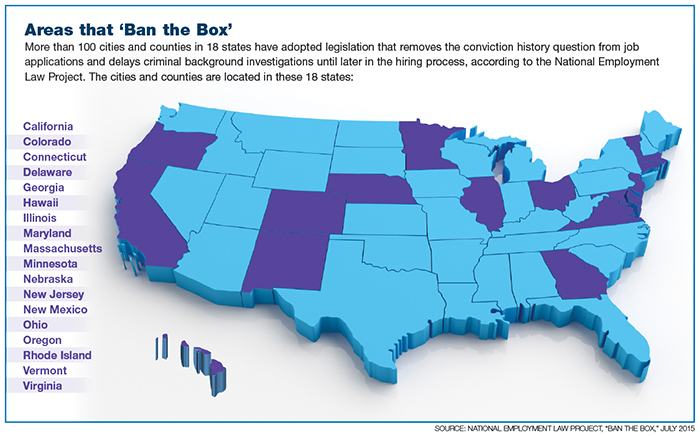

As of now, 18 states have adopted “ban-the-box” policies for public sector jobs.

Seven of those states have made private employers and government contractors remove the conviction history question on job applications as well.

The National Employment Law Project (NELP), a major advocate for making the change, also reports that currently there are more than 100 cities and counties that have adopted ban-the-box laws and 25 municipalities that have extended the ban to the private sector.

In NELP’s view, ban-the-box initiatives provide applicants a fair chance by delaying the background check inquiry until later in the hiring process. There are opponents, primarily some U.S. business and industry groups.

For example, the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), which counts mainly small employers among its 350,000 members, says on its website that ban-the-box laws would “unduly suppress relevant criminal record information” about prospective employees.

The NFIB added that without having that information, employers can’t protect their business from loss or secure the safety of their employees, vendors and the general public when making hiring decisions.

Opponents could be swimming against the tide. Apple, for instance, recently changed a policy that prohibited construction workers with felony convictions from working on its new campus construction in Cupertino, Calif.

Construction workers who lost their jobs because of felony convictions within the past seven years will now be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Wal-Mart, the nation’s largest employer, took the checkbox off its job applications in 2010. Target Corp. and Bed Bath & Beyond are other national retailers that stopped asking about an applicant’s conviction record during the hiring processes’ initial phase.

Laura Kerekes, chief knowledge officer at ThinkHR Corp., in Pleasanton, Calif., said the momentum for adopting ban-the-box legislation is increasing. Removing the box from the application allows organizations to focus on an applicant’s qualifications in the early stages of the hiring process.

It gives the applicant a fair chance to showcase his or her talents early and put the criminal infraction in perspective with the applicant’s potential to be a great employee.

“Not all of these laws apply to every employer,” Kerekes said.

“Most apply to public employers and government contractors receiving public funds, while some also apply to private employers.”

“Not all of these laws apply to every employer.” — Laura Kerekes, chief knowledge officer, ThinkHR Corp

She added that some of the laws are based on employer size, so small employers (10 employees or less) usually are exempt from these rules.

However, most ban-the-box laws today, though different from state to state and city to city, share features that either prohibit employers from asking job applicants about prior convictions or conducting criminal background checks on applicants prior to either a first live interview or a conditional offer of employment.

They also force employers to consider the amount of time that has elapsed since the conviction and what the applicant has done since, as well as consider only the conviction information that is directly relevant to the job being considered — such as credit or tax issues for positions in finance and accounting or offenses against children for teaching or child care positions.

Talent Shortage Plays a Part

“This issue has become a hot topic for our customers in some industries or regions, particularly in the financial services, hospitality and other services industries,” she said, adding that the job market is heating up, making the demand for key talent much harder to source and hire.

In addition to the hiring challenges they face, employers are focused on ensuring compliance with a myriad of regulatory rules, including negligent hiring and ban-the-box laws.

Sheryl Jaffee Halpern, a principal and chair of the labor and employment group at Much Shelist in Chicago, advises clients to eliminate the criminal question checkbox.

Instead, she said, job applications should include a statement that indicates the candidate consents to a background check as a condition of employment.

“It’s really accomplishing the same thing, which is finding out if there is a criminal history,” she said.

“But you are going about it in a way that doesn’t dismiss a job candidate for just admitting to having been convicted of a crime.”

Jaffee Halpern said the key is to tackle the issue candidate-by-candidate, conviction-by-conviction. For example, a 52-year-old job candidate could have shoplifted at 18, which means the information is pretty much irrelevant.

“If it’s a more recent, violent crime, that’s a different conversation,” she said.

Basically, she said, employers — both risk managers and HR leaders — must set a policy that determines if the decision to disqualify is “job-related and consistent with business necessity.”

“Just because an employer gets rid of the checkbox doesn’t mean they can’t do background checks and due diligence,” she said, adding that many times the decision to hire or not comes down to an instinctual comfort level.

“Just because an employer gets rid of the checkbox doesn’t mean that can’t do background checks and due diligence.” — Sheryl Jaffee Halpern, principal and chair, labor and employment group, Much Shelist

Bob Tice, an attorney in employment law at Collins Einhorn in Southfield, Mich., noted that along with ban-the-box laws there is an ongoing legislative trend to reintegrate ex-offenders into the workforce.

Nonetheless, Tice said criminal history questions can legitimately influence employment decisions, notwithstanding the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s efforts to rein in what it sees as discriminatory hiring patterns against black and Hispanic job applicants by the use of criminal background checks.

In 2012, the EEOC issued new rules around arrest and conviction records in employment decisions under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Soon thereafter, it sued both BMW and Dollar General, saying both had discriminated against minority job candidates through criminal background checks, a broader scenario than just a checkbox.

IP and Cyber Security Risks

Both cases are pending, but the EEOC has suffered some setbacks in court — mainly one involving PeopleMark Inc., a staffing agency — in which the EEOC had to pay $750,000 in legal fees and other court costs to PeopleMark.

There are legitimate nondiscriminatory business reasons that employers have questions about honesty of employees, Tice said.

“It’s not just about stealing cash or materials, but today it’s also intellectual property, digital materials, cyber security, that type of thing.”

Tice’s ongoing recommendation is to take the box off applications and don’t automatically exclude someone. Then after the first interview, depending on the job, there may be a valid reason to exclude someone.

“One of the best things about that approach is you are only dealing with that one person,” he said.

When companies use the checkbox, it may inadvertently be racially profiling job candidates, Tice said.

When companies use the checkbox, it may inadvertently be racially profiling job candidates, Tice said.

James Reid, a shareholder at Maddin Hauser, also recommended doing interviews before any background checks.

“It is time for the checkbox to go,” he said.

He also advises employers to stay far away from social media to eliminate any possible bias until an interview is conducted.

“Anyone can get a misdemeanor charge and employers can be losing a huge talent pool. A person could have been in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

He noted that with the majority of the ban-the-box laws, employers are allowed to ask applicants about criminal records after the first interview.

That way, once they discover a person has a criminal record, they can find out what the crime was and the specific circumstances, and may end up hiring them anyway.

“It’s a good idea to use more than the checkbox before you throw their application on the junk pile,” he said.

ThinkHR’s Kerekes said the first step for organizations is to determine whether the ban-the-box laws apply to the organization.

Next, employers must consider each statute if it operates in multiple locations and determine whether to follow location-specific regulations or to consolidate the regulations into one “super policy” to be followed by the entire company.

In the latter case, the employer will need to follow the rules most favorable to the applicant. After all, she said, there is no real reason to wait for legal mandates to make the change and ban the box.

Once the strategy is defined, the regulations reviewed and rules developed, there are other critical steps for organizations to take, including:

- Revise employment applications and all other employment materials to ensure that they comply with the law and company policies.

- Review jobs within the organization to determine which positions require a criminal background check (those that require unsupervised access to sensitive work areas, handle sensitive or financial information, or work with children or the elderly, etc.) and how far back in the applicant’s job history to probe.

- Review and revise the background checking policy and practices to reflect the company strategy.

- Develop a process for notifying those applying for positions requiring criminal records check (both before the check and afterward, especially if the applicant will be rejected from the position).

- Determine when and who will ask the relevant questions about criminal backgrounds.

- Train all managers and those involved in the hiring process regarding employment and discrimination law and the process and timing for asking about criminal backgrounds.

- Conduct a thorough review and assessment of each applicant, based on objective criteria.

“Not all employers legally must ban the box,” Kerekes said.

“But every employer should follow the trend because it is gaining momentum, and also tighten up hiring processes to comply with legal requirements while creating a great user experience for all applicants.”