Reputational Risk

Under Siege

On Jan. 28, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance called a strike at John F. Kennedy International Airport, one day after President Trump signed an executive order banning entry of foreign nationals from seven Muslim-majority nations, including a blanket ban on refugees. The strike was an act of solidarity with immigrants, and a public display of the Alliance’s opposition to the executive order.

Uber, however, continued to service the airport, tweeting that it would halt surge pricing during the protests. Some saw it as an opportunistic ploy to get more riders to use Uber. A #deleteUber Twitter campaign was quickly born, with users tweeting screen shots of themselves removing the app from their smartphones.

More than 200,000 were estimated to have uninstalled the ride-sharing service over the course of the weekend.

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick reacted, creating a $3 million legal defense fund to provide lawyers and immigration experts for any of its drivers that were barred from the U.S., and promising that drivers would be compensated for lost wages.

Over the same weekend, in response to the travel ban, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz announced that the company would hire 10,000 refugees worldwide over the next five years. Then it was Starbucks turn to get punished in the public arena. A #boycottStarbucks campaign was launched by people who felt the company should focus more on hiring American veterans.

Athletic shoemaker New Balance suffered blowback in November of 2016 when its vice president of communications, Matt LeBretton, told the “Wall Street Journal” in an interview that he believed “things are going to move in the right direction” under the new administration. Angry customers began posting pictures of themselves trashing or even burning their New Balance sneakers.

These social media-fueled public relations crises demonstrate how fickle public opinion can be. They also serve as warning signs of growing reputational risk for corporations.

Uber, for example, typically stops its surge pricing in the event of emergency so as not to exploit a crisis for its own benefit. To do so during the protests and taxi strike at JFK was perhaps meant to show its respect for the event.

Starbucks’ 10,000 refugee hires would be spread out across its locations around the globe, not just in the U.S., where the coffee conglomerate already promised to hire 25,000 veterans and military spouses by 2025.

New Balance’s LeBretton was speaking specifically about the Trans-Pacific Partnership during his interview, and how the deal could hurt sneaker production in the U.S. while favoring foreign producers — he wasn’t talking about Trump’s other proposed plans.

These companies, in reality, did nothing as abhorrent and scandalous as the Twitterverse may have led some to believe, but context isn’t always provided in 140 characters.

Public Pressure

Complaints and boycotts have been launched at companies via social media for perhaps as long as social media has existed. But the current contentious environment created by one of the most divisive leaders in American history now colors every public statement made by prominent business leaders with a political tint. Executives are stuck between a rock and a hard place. They’re exposed to reputational damage whether they oppose or endorse a Trump action, or even if they do nothing at all.

Take Elon Musk, for example, founder of Tesla and SpaceX and a well-known advocate for climate research and environmental protection. He came under fire for not publicly denouncing the travel ban and for keeping his seat on Trump’s business advisory council.

Musk has largely avoided the limelight on political issues, couching statements when he makes them at all — as most executives are wont to do. But he was prodded to defend himself on Twitter after some users suggested he was a hypocrite.

“Be proactive in your plans to mitigate the aftermath and how to communicate. Own up to error. Be transparent. Salvage your crown jewel.” —Helen Chue, global risk manager, Facebook

A strategy of avoidance may no longer work as consumers, employees and the public at large pressure companies to make a statement or take action in response to political events.

“A large segment of the population expects the people they do business with and the companies they buy from to support their point of view or respond to political or social issues in a certain way,” said Chrystina M. Howard, senior vice president, strategic risk consulting, Willis Towers Watson.

In a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t environment, reputation risk is expanding, and risk managers need to re-evaluate how they assess their exposure and build mitigation strategies.

A True Crisis?

The challenge begins with determining whether a negative public relations event is really a crisis. Is it a temporary blow to a brand, or does it have the potential to do long-term reputation damage? Misreading the signs could lead companies to overreact and further tarnish their image.

“These sudden public relations crises are a source of panic for companies, but sometimes it sounds much worse than it actually is. The financial ramifications may not be anywhere near what was feared,” Howard said.

“Uber is probably a good example of what not to do,” said Jeff Cartwright, director of communications at Morning Consult, a brand and political intelligence firm.

“They maybe went over the top in trying to reverse the way they handled the protests at JFK.”

Tracking brand value in real time can give risk managers insight into the true impact of a negative social media campaign or bad press. Michael Ramlet, CEO and co-founder of Morning Consult, said most events don’t damage brands as much as trending hashtags make it appear.

Tracking brand value in real time can give risk managers insight into the true impact of a negative social media campaign or bad press. Michael Ramlet, CEO and co-founder of Morning Consult, said most events don’t damage brands as much as trending hashtags make it appear.

Morning Consult’s proprietary brand tracking tool allows companies to measure their brand perception against influencing events like a spike of Twitter mentions and news stories. More often than not, overall brand loyalty remains on par with industry averages.

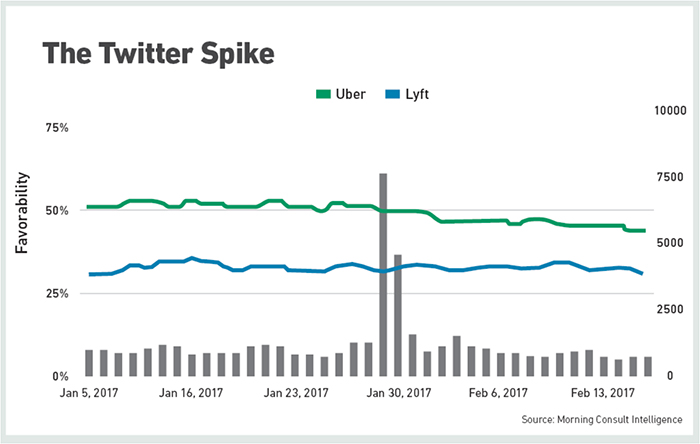

In Uber’s case, Twitter mentions spiked to roughly 8,800 on Jan. 29, up from about 1,000 the day before. By Jan. 31, though, the number was back down to around 1,250 and quickly settled back down to its average numbers. From the beginning of the #deleteUber campaign through the end of February, Uber’s favorability shrunk from 50 percent to roughly 40 percent, based on a series of polls taken by 18,908 respondents.

It’s a significant dip, but likely not a permanent stain on the company’s reputation, especially after Kalanick’s public show of support for immigrants and rejection of the travel ban. Uber’s favorability rating remained higher than competitor Lyft’s throughout the ordeal.

“The #deleteUber campaign turned out to be a very local thing that didn’t have a widespread impact,” Ramlet said.

“Twitter at best is an imputed analysis of what people are saying. The vocal minority might be very active, but there might be a silent majority who still think fondly of a brand, or at least have no negative opinions of it.”

He said risk managers can also benefit by breaking down their brand perception into geographic and demographic subsets. It can, for example, show whether a brand is favored more heavily by Democrats or Republicans.

“If you have that data on day one, it can help you determine how to respond if, say, Trump tweets at you,” Ramlet said.

Of course, some spikes in news media and social media attention are indicative of much deeper problems and true reputational risk.

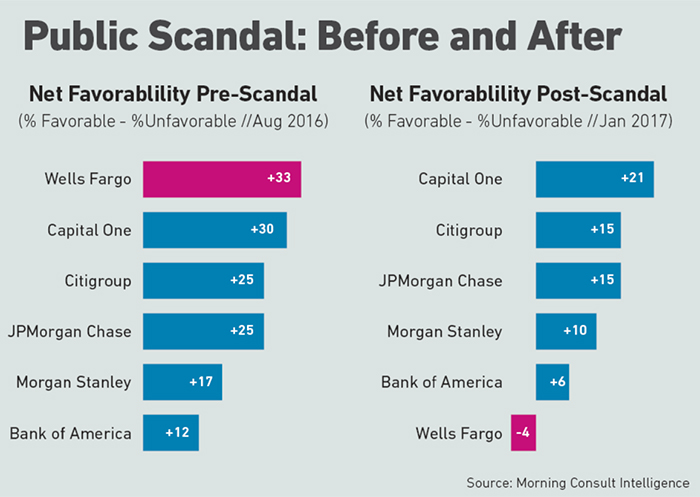

After the Wells Fargo dummy-account scandal broke, for example, unfavorability ratings as measured by Morning Consult jumped from roughly 20 percent to nearly 55 percent, while favorability dropped from 50 percent to 30 percent. Net favorability, which stood at 33 percent pre-scandal, fell to -4 percent post-scandal.

“They went from being the most popular bank to the least popular in less than four months, according to our data,” Ramlet said.

The contrast between Uber’s and Wells Fargo’s stories demonstrates the difference between a more surface-level public-relations event that temporarily hurts brand image, and a true reputation event.

“Failures that produce real and lasting damage to reputation include failures of ethics, innovation, safety, security, quality and sustainability,” said Nir Kossovksy, CEO of Steel City Re.

“Activists make a lot of noise that can be channeled through various media, but for the most part in the business world, stakeholders are interested in the goods and services a company offers, not in their political or social views. As long as you can meet stakeholder expectations, you avoid long-term reputational damage.”

Wells Fargo’s scandal involved a violation of ethics, sparked an SEC investigation and forced the resignation of its CEO, John Stumpf. It’s safe to say stakeholders were severely disappointed.

That’s not to say, however, that a tarnished brand name doesn’t also impact the bottom line.

“Even if a bad event is short-lived, the equity markets react quickly, so there may be sharp equity dips. There may be some economic impact even over the short term,” Kossovsky said, “because sharp dips are dog whistles for activists, litigators and corporate raiders.”

Social Media Machine

The root of reputation risk’s tightening grip lies in the politicizing of business, and consumers’ increased desire to buy from companies that share their values. Social media may not be driving that trend, but it acts as a vehicle for it.

“Social media has really changed the game in terms of brand equity, and has given people another way to choose who they give their money to,” Howard of Willis Towers Watson said.

Platforms like Twitter make it easier for consumers to directly reach out to big companies and allow news to travel at warp speed.

“Social media are communication channels that can take a story and make it widely available. In that regard, the media risk is no different than that posed by a newspaper or radio channel,” Kossovsky said.

“The difference today that changes the strategy for risk managers and boards is that social media has been weaponized: Stories shared on social media don’t necessarily have to contain truthful content, and there’s not always an obvious difference between what’s true and what’s not.”

Helen Chue, Facebook’s global risk manager, agreed.

“More influential than social media platforms is today’s culture of immediacy and headlines. Because we are inundated with information from so many sources, we scan the headlines, form our opinions and go from there,” she said.

“It’s dangerous to draw conclusions without taking a balanced approach, but who has the time and patience to sift through all the different viewpoints?”

An environment of political divisiveness, driven by speed and immediacy of social media, creates the risk that false or half-true stories are disseminated before companies have a chance to clarify. This is what happened to Uber and New Balance.

“It creates the opportunity to turn a non-problem into a problem,” Kossovksy said.

“That’s how social media changes the calculus of risk management.”

Risk Mitigation

The best way to battle both political pressure and social media’s speed is through an ironclad communication strategy; a process that risk managers can lead.

“Risk managers play a crucial role in mitigating reputation risk,” Howard said.

“They bring with them the discipline of managing and monitoring a risk, having a plan and responding to crisis. Now they really have to partner with communications, marketing and PR.”

They also have to get the attention of their board of directors.

“If you let a gap form between what you say and what you do, that gap is the definition of reputation risk.” — Nir Kossovksy, CEO of Steel City Re

“This is both a company-wide risk and personal leadership risk, so the board needs to drive a company-wide policy that protects the board as well,” Kossovsky said.

The art of mitigating reputation risk, he said, comes down to managing expectations. Corporate communications should clearly convey what a company believes and what it does not believe; what it can do and what it can’t do. And those stated values need to align with the operational reality. It comes down to creating credibility and legitimacy.

“If you let a gap form between what you say and what you do, that gap is the definition of reputation risk,” he said. A strong communication strategy can prevent adverse events from turning into reputational threats.

Willis Towers Watson helps clients test their strategies through a table-top exercise in which they have to respond to a social media-driven reputation event.

“We’ll say, ‘Something happened with X product, and now everyone’s on Twitter lambasting you and calling for resignations, etc.’ What do you do on day one? What do you do a week out? How long do you continue to monitor it and keep it on your radar?” Howard said.

“If you have that plan in place, you can fine-tune it going forward as circumstances change.”

Sometimes, though, the communication strategy fails, and a company falls short of meeting stakeholders’ expectations. Now it’s time for crisis management.

“Volatility creates vulnerability. If you stumble on your corporate message, it creates an opportunity for activists, litigators and corporate raiders to exploit. So you need to have authoritative third parties who can attest to your credibility and affirm the truth of the situation to open-minded stakeholders,” Kossovsky said.

Owning up to any mistakes, reaffirming the truth and being as transparent as possible will be key in any response plan.

Insuring the Risk

Recouping dollars lost from reputation damage requires a blend of mathematics with a little magic. While some traditional products are available, reputation risk is, for the most part, an intangible and uninsurable risk.

“Many companies have leveraged their captive insurance companies in the absence of traditional reputation products in the marketplace,” said Derrick Easton, managing director, alternative risk transfer solutions practice, Willis Towers Watson.

“It goes back to measuring a loss that can include lost revenue, or increased costs. Some companies build indexes in the same way we might create an index for a weather product, using rainfall or wind speed. For reputation, we might use stock price or a more refined index,” he said.

“If we can measure a potential loss, we can build a financing structure.”

While there’s no clear-cut way to measure losses from reputation damage, “stock performance and reported sales changes are some of the best tools we have,” Howard said.

While there’s no clear-cut way to measure losses from reputation damage, “stock performance and reported sales changes are some of the best tools we have,” Howard said.

Some insurers, including Allianz and Tokiomarine Kiln, and Steel City Re, an MGA, do offer reputation policies. When these fit a company’s needs, they have the ancillary benefit of affirming quality of governance and sending a signal that the insured is prepared to defend itself.

“Because reputation assurance is only available to companies that have demonstrated sound governance processes, it helps to convince people that if a bad piece of news happens, it’s idiosyncratic; it doesn’t reflect what the company really stands for,” Kossovsky of Steel City Re said.

“And it tells activists, broadly defined, not to look for low-hanging fruit here.”

In a volatile political environment, companies fare best when they simply tell the truth.

“The American public will accept an apology if delivered quickly and if it’s sincere,” said Stephen Greyser, Richard P. Chapman professor (marketing/communications) emeritus, of the Harvard Business School.

“Tell the truth. Don’t stonewall. A bad social media campaign can be an embarrassment, but if you stick to the facts and apologize when you need to, people forget about the bad quickly.”

“Reputation is the crown jewel,” Chue said. “Given the power of social media’s reach, one individual can have a tsunami-like influence. And it can happen when you least expect it, and it will probably be something you thought was innocuous or even positive that sets off a maelstrom.

“Plan for the worst-case scenario. Be proactive in your plans to mitigate the aftermath and how to communicate. Own up to error. Be transparent. Salvage your crown jewel.” &