Environmental Liability

Tight Rules and Low Funding Challenge Tank Operators

Late last year, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker made almost $100 million in mid-year budget cuts to fill an anticipated shortfall. Of that, he cut $3 million from the program that maintains and inspects underground storage tanks (USTs) for hydrocarbons. The cut was just 3 percent above the overall budget reduction, but as the UST program was only $10 million to start, the cut is a substantial 30 percent of the funding.

Moreover, the timing could hardly be worse: The state mandated that all single-wall tanks be removed by Aug. 7. The actual removal process is only a matter of a few days for most tanks, but contractors must be booked in advance and digging is difficult in frozen ground, so the window for work is only four or five months. Also, double-walled regulatory-compliant replacement tanks must be ordered well in advance from fabricators.

And so it goes around the country. Many states are tightening rules on USTs, and some have reduced the pools of money set aside for remediation. That has thrown operators of all sizes back into the risk-transfer market. Some can put up surety bonds, but more and more are buying insurance-like limited tank-only coverage, or adding tank endorsements to their pollution legal liability (PLL) covers.

And so it goes around the country. Many states are tightening rules on USTs, and some have reduced the pools of money set aside for remediation. That has thrown operators of all sizes back into the risk-transfer market. Some can put up surety bonds, but more and more are buying insurance-like limited tank-only coverage, or adding tank endorsements to their pollution legal liability (PLL) covers.

UST Coverage Trends

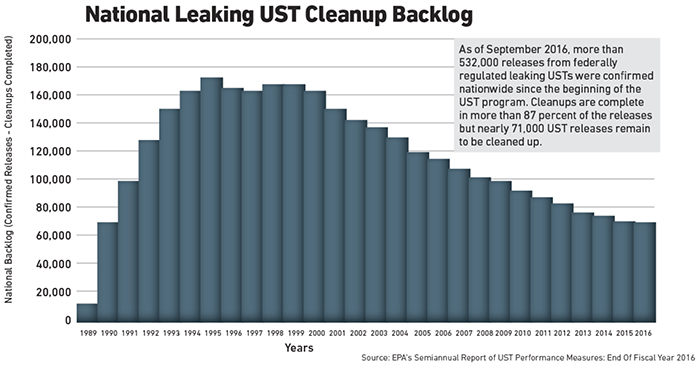

There are about a half-million USTs registered with the Environmental Protection Agency. That translates to an insurance market estimated to be $50 million to 60 million in annual premium, according to underwriters and brokers.

Chubb is one of the major carriers, having increased its share through its merger with ACE. Liberty and AIG are also said to have a presence, among others. Brokers report some turnover among carriers, with Zurich having left the segment in 2012.

“There are three ways to certify financial responsibility,” said Gerry Rojewski, senior vice president and chief underwriting officer for Chubb Environmental. “You can self insure. Or you can rely on state funds. Or you can purchase risk transfer.”

“Not surprisingly, the older tanks had higher rates of failure, but there are lots of variables. Larger operations have more assets to cover, but may be a better risk because they have more resources.” — Gerry Rojewski, senior vice president, chief underwriting officer, Chubb Environmental

The decision varies with the size of the owner’s operation and the number and age of tanks. “Some owners go through agents and some go direct to the market,” said Chris Smy, environmental practice leader at Marsh. “Our clients run the gamut from a hotel that has a backup generator and a small UST for diesel fuel, to large energy companies with many tanks. The business is not just what you might think of, like a retail gas station. It could be anyone.”

Even in states that have funds, there are complications.

“State funds have dried up or faced delays in reimbursement,” said Jeffrey Hanneman, managing director at Aon Risk Services Southwest. “Texas and Florida, for example, no longer have state funds. Even in California, which does have a fund, there is a priority for reimbursing in order inverse to size. It is impossible to know if or when an operator will recoup UST expenses or how much. We have some clients who do not ever anticipate recouping.”

As a result of that smallest-first preference, Hanneman said, Aon’s customers tend to be larger operators in contrast to the mom-and-pop retail service centers.

The biggest challenge for USTs is age, said Rojewski.

“In some cases, the owner/operator may try to keep a UST in service beyond its designed lifecycle of 30 years. Replacing a UST can be a significant investment. Not all owner/operators feel the need to replace the tank at this line of demarcation especially if tightness testing results are positive.”

Rojewski added that Chubb conducted a predictive modeling study on tank exposures. The results showed that the older tanks had a higher probability of leaking, he said, but the study also revealed a host of other variables.

“Large operations with higher exposures versus small operations with less complex risk present a different set of characteristics for an insurance carrier,” he said.

“Larger risks may have more assets and may develop more comprehensive risk management programs as opposed to a smaller company, which may not have those types of resources available.”

Rojewski said that Chubb “has the ability to write tank insurance through an online portal called Tanksafe, or through our underwriting team based in Philadelphia, which can work with clients and brokers.”

Smy at Marsh suggested that the current trend within UST coverage is to broaden pollution policies with tank endorsements.

“Other clients are electing to go with above-ground tanks when they replace USTs,” he added. “And still others that have pollution liability feel comfortable retaining the risk for their tanks. In such cases where regulations mandate a demonstrated financial assurance, most owners make the choice to go with risk transfer by insurance.”

To that point, Smy stressed that broad pollution covers “are not a catch-all for USTs. They have to be scheduled. The only tanks covered without a schedule are so-called phantom tanks, ones that are not known until found.”

Challenges with Aging Tanks

Brokers say that while the sector is stable, and even has some growth potential as state funding dwindles, there are challenges.

“The longer you go insuring, the more likely you are to have to pay out,” says Smy.

“Carriers are pushing back on covering tanks of a certain age regardless of whether or not they have passed tests. There is just less and less appetite for aging tanks. Operators are going to have to start replacing them.”

Testing is part of all state regulatory requirements.

“Even self-insureds have to pass their tank tests,” said Hanneman at Aon.

He added that there are tanks that can pass the structural test, but small operators that struggle to demonstrate financial responsibility, and also the reverse.

“Because there is a strong correlation between age and loss, owners have to test every year. And most underwriters want to see those integrity test results. The age and condition of tanks, or anticipated replacement costs, are often figured into the price of any sale of assets.”

It bears mentioning that while most retail fuel operations have national brand names, only about 3 percent of the gas stations are actually owned by the big oil companies.

The other 97 percent are owned either by the operator, or are franchises of a regional or national chain. There is a slow but steady cycle of stations being sold both to and from larger and smaller owners.

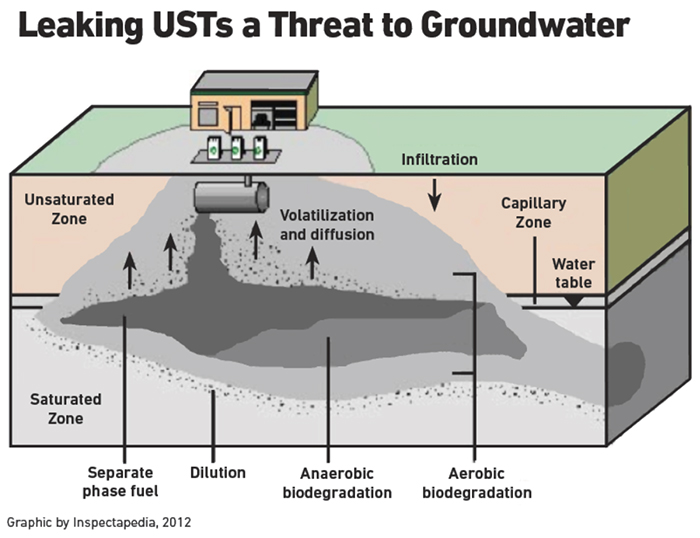

“Most policies have a $1 million limit with $2 million aggregate,” said Hanneman. “A simple leak cleanup will run in that range, $1 million to $2 million. If the leak gets into the ground water it can be more.”

“Most policies have a $1 million limit with $2 million aggregate,” said Hanneman. “A simple leak cleanup will run in that range, $1 million to $2 million. If the leak gets into the ground water it can be more.”

Given that oil floats on water, the water table in the region and the permeability of soil are big factors. That is why southern states tend to see more spill migration than do northern states, even with their freeze-thaw cycles.

Research from the EPA also implicates metal corrosion as a growing problem with USTs. A 2016 study of 42 operational diesel tanks concluded that 35 of them, or 83 percent, exhibited moderate or severe corrosion.

While this can lead to vapors escaping into the surrounding soil, corrosion can also lead to equipment failure, including the failure of release and detection systems. While the issue is not widespread among non-diesel tanks, the likelihood of corrosion increases with age and presents another factor to consider.

Brokers also note that larger clients tend to keep tanks on their policies even after sites have been sold. For them the incremental costs of a few more tanks on the schedule is not daunting.

And even though buyers become owners with full responsibility, with indemnification for sellers, that does not stop lawsuits from being filed if current owners go bankrupt and lawyers follow the deed back. &