Reduced Pilot Hours Are Dangerous. Some Risk Management Imperatives to Consider

The impact of COVID-19 on the aviation industry has been undeniable and well documented — perhaps so much so that for the first time in years, we’re talking about something other than the impact of drones.

Passenger volume for commercial airlines was down 60% in 2020, and new general aviation (GA) — or private — aircraft deliveries decreased 21% at the beginning of the pandemic.

We found ourselves longing for the thrill of waiting in TSA lines hoping we wouldn’t miss our flights.

While the impact on the entire aviation industry in general is staggering, GA owners and operators face potentially more pronounced issues than the commercial airline industry. Airline pilots facing furloughs will have access to sophisticated company simulators to hone their skills before returning to the skies and airlines have dedicated maintenance teams; GA pilots don’t have the same luxuries.

Data isn’t out on GA flight hours for 2020, but there’s no shortage of anecdotal evidence to show that the numbers will be down.

With airplanes sitting on the ground, there are two forms of rust that pose significant risks as pilots prepare to take to the skies — pilot recency and equipment corrosion.

Pilot Proficiency

It’s well-established that there is an inverse relationship between flight hours and safety.

The fewer the flight hours, the greater the safety risk.

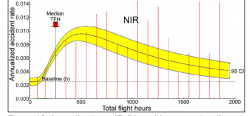

However, there is one exception to this rule for newer pilots. As pilots gain a little experience and self-assurance, they tend to become overconfident in their skills and exceed their limitations, greatly increasing the likelihood of making mistakes. The FAA confirmed as much with the graph below, which shows a peak in accident rates around 500 hours of experience for non-instrument rated pilots, before returning to the baseline rate around 2,000 hours.

Looking at the chart above, a pilot could find his or her place on the graph and get an estimate of the accident rate. However, reduced flight time during the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted the focus from flight hours to recency and proficiency, two areas that are not as well researched when it comes to risk assessment of pilot safety.

While the FAA’s flight recency requirements sometimes feel like a burden, they exist for a reason. Practice is key to maintaining proficiency in any activity, whether it’s flying, golf, surgery or piano.

As they say, practice makes perfect. In the absence of practice, skills erode and errors occur.

As previously stated, there is an increase in risk once pilots gain a bit of experience and confidence. A pilot returning to the skies post-pandemic may experience the same effect but on a smaller scale: The first few flights go well, a pilot feels confident despite not having much practice, then pushes the envelope, leading to disaster.

What we’re worried about is the same risk experience curve but in terms of recency of experience instead of total hours of experience.

Having one successful instrument approach may bring back a high level of confidence, but it is important for pilots to truly analyze whether that confidence translates into proficiency when attempting the same approach in instrument meteorological conditions, when weather conditions require pilots to fly primarily relying on instruments rather than visual reference.

Rusty proficiency is not just limited to pilots.

Airports and Fixed Base Operator ground crews that handle private aviation had layoffs during the pandemic, controllers handled less traffic, and even the passengers appear to have forgotten things about flying, such as where to find the lavatory.

Simply put, every cog in the machine of aviation has ground to a halt, and it’s incumbent on the industry to take extra precautions as we emerge from the pandemic.

Even if you’re confident your flying ability is corrosion free after a long break, there are going to be other pilots who may have forgotten an airport layout they once knew or miss a frequency they thought they memorized, or linemen who are rusty with how they marshal aircraft. Pilots should keep a keen eye out, not just for their mistakes, but also for the mistakes of their fellow aviators.

Aircraft Safety

In addition to risks posed by the human error element of aviation, there’s another type of rust that poses a big risk for the GA industry: aircraft that have been sitting on the ramp or in hangars are at risk of corrosion.

The pandemic presented a unique change to the typical process of preserving an aircraft for periods of inactivity.

While an aircraft owner can typically anticipate when their aircraft will sit idle, COVID-19 caught us all by surprise. Aircraft may have been sitting on the ramp for months before owners realized this pandemic would not be over any time soon.

Many aircraft require preservation steps be taken if the aircraft will be idle for more than 30 or 60 days. These aircraft will need thorough inspection and possible repairs before flying if they were not properly preserved during the pandemic.

In regions with high humidity or salt content, these issues will be especially pronounced.

Financial pressures of COVID-19 and the lack of flight hours have resulted in some owners deferring maintenance until the end of the pandemic. It is critical that these items are addressed before returning to service. Even aircrafts stored in a heated hangar are subject to degradation over time due to corrosion, internal seal aging and the breakdown of internal lubricants.

While it’s painful to pay for an overhaul or replacement of parts on an aircraft that hasn’t been used for a year, these guidelines exist to keep crews and passengers safe.

Insurance Considerations

Once pilot proficiency and aircraft maintenance issues have been addressed, there are additional risk mitigation steps GA owners and operators need to take before heading back into the skies:

- First, check with your insurance broker to make sure you have active coverage for all operations if you’ve changed or dropped coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Second, read through the policy to see if there are instrument flight rules, currency or other specialized training requirements. Failure to comply with these provisions could invalidate coverage in the event of an accident.

- Third, pay close attention to maintenance, because wear and tear or mechanical failures are typically not covered, and if your aircraft is unairworthy it could invalidate coverage.

- Finally, while we applaud those of you starting your engines during the pandemic, one of the most frequent claims we’ve seen during this time is forgetting to detach a tow-bar before those ground run-ups. We can’t highlight the importance of taking your time and following proper procedures enough. Contrary to the old adage, flying is not like riding a bike, unless you ride your bike with a checklist.

In Conclusion

COVID-19 has presented extraordinary challenges for the aviation industry and the world in general. Pilots should be vigilant in ensuring their proficiency after a time off from flying, be aware of the possible proficiency issues of those around them and be mindful that aircraft may need a tune up after all that time on the ground.

Once pilot and aircraft proficiency is assured, GA owners and operators should consult with their insurance brokers to make sure their coverage is up-to-date as well.

As tempting as it is to rush to return to the skies, we must, as we always do, proceed with the healthy respect and caution that drives the constant safety diligence. &