Cover Story

Raising the Costa Concordia

The plan to raise the Costa Concordia — the largest and most expensive wreck removal operation in maritime history — is a marine engineering marvel. But a successful outcome is far from assured and the cost is approaching $1 billion.

When the massive Costa Concordia passenger ship ran aground on Jan. 13, 2012, claiming 32 lives, it entered the marine insurance record books.

Hull insurance on the vessel, at more than $500 million, is now paid off by insurers, which include XL, Generali and RSA.

But the removal of the wreck of the Costa Concordia, the largest such project ever attempted, is driving costs onto additional insurers that could reach $1 billion. Those carriers include P&I (protection and indemnity) clubs, which are, in essence, marine mutual insurers owned by ship owners and related interests.

Those charged with righting the decaying ship and plucking it off the reef are in a bind. Each day on the reef weakens the ship’s hull. Magnifying the ship recovery risk is the size of the Costa Concordia. The ship measures about the length of three football fields and weighs 114,500 gross tons.

By far, the biggest complication is the fact that the ship is wrecked in the environmentally sensitive Tuscan Archipelago National Park, a protected coral reef as well as a popular tourist destination.

The wreck must be removed whole in order to avoid releasing a swamp of debris and pollutants into the waters. For this reason, the Italian government is paying close attention to the project.

The need to remove the wreck in one piece left only the most expensive recovery option open: parbuckling and re-floating. Parbuckling, which refers to the process of rolling the ship back up to an upright position, is not a new invention. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. military recovered the capsized USS Oklahoma in much the same way. For the Concordia though, the costs involved in such an undertaking would be extraordinary.

“The instructions are ‘Get it off [the reef] and we’ll worry about costs later,’ which is the worst thing for an underwriter to hear,” said Steven Weiss, vice president, Marine Engineering and Project Cargo with Liberty International Underwriters.

Just as troubling as the cost, the shadow hanging over the plan is that a parbuckling operation has never been attempted on a ship anywhere near the size of the Costa Concordia. Even now, some still have doubts about whether it can really be done.

Getting Ready To Roll

From the moment the Costa Concordia came to rest on the reef, the race was on to avoid an environmental catastrophe. The ship was still carrying 2,300 tons of diesel fuel.

Dutch salvor Smit Salvage was brought in to pump out Concordia’s 17 fuel tanks — not as straightforward a task as it might seem. Draining the tanks would shift the vessel’s equilibrium, likely causing it to topple off the reef and sink, hemorrhaging fuel in its wake.

Smit used a process called hot-tapping, a painstaking method of pumping hot water into the vessel at the exact same rate that fuel is being pumped out, in order to keep the weight constant.

The fuel removal process alone took a team of 100 experts from around the world, with the aid of 20 platforms, tugs, transport ships, crane barges, tankers and oil spill response vessels. However, the 31-day operation was just a warm-up for the work that would soon begin.

The contract to remove the wreck was awarded to a team comprised of Florida-based salvor Titan Salvage and Italian marine engineer Micoperi. The Titan-Micoperi plan has engaged 450-plus crewmen and divers from 19 countries, working around the clock for more than a year, with a menagerie of least 25 marine vessels and crafts operating at any given time.

“The number of engineers and amount of computing time they’ve used on this was probably equivalent to the first moon landing,” said John Phillips, vice president, Marine Hull, Liability & Cargo, Liberty International Underwriters.

That’s probably not far from the mark — it took three supercomputers running for weeks to model the wreck removal plan.

Work on the project began in June 2012, but parbuckling remained a distant goal. Every day that the ship lay on its underwater perch, it remained in danger of sliding down the steep seabed and sinking into 230-foot deep water, likely breaking apart in the process. Divers spent months stabilizing the vessel, securing it with chains, cables and anchor blocks to prevent it from becoming dislodged prematurely.

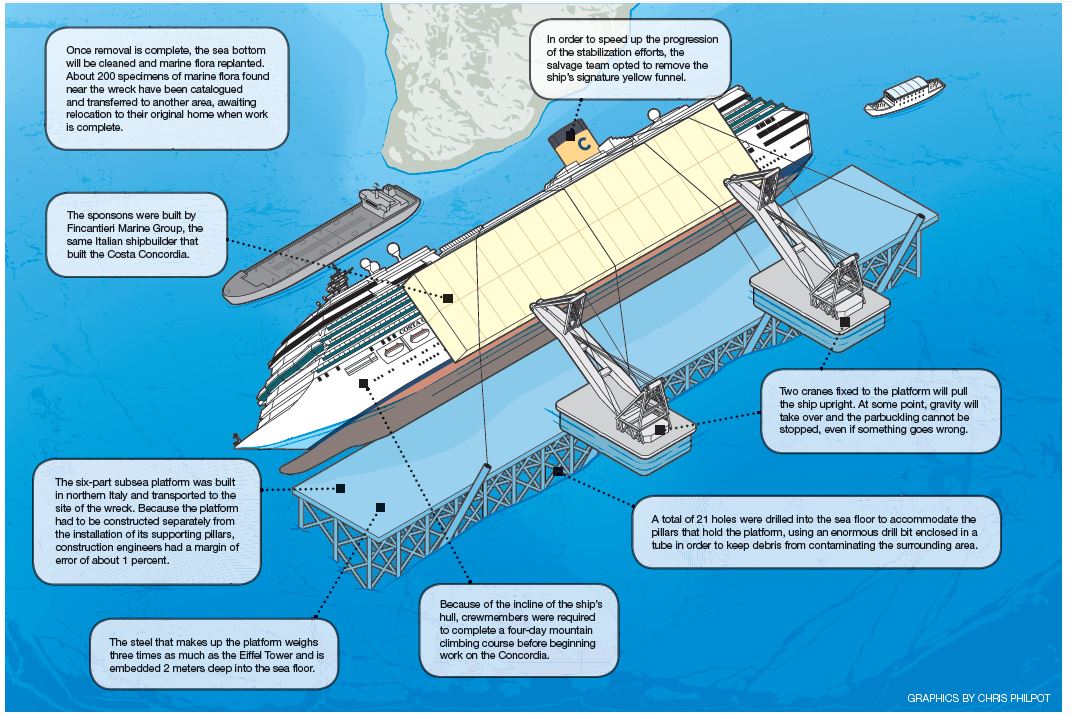

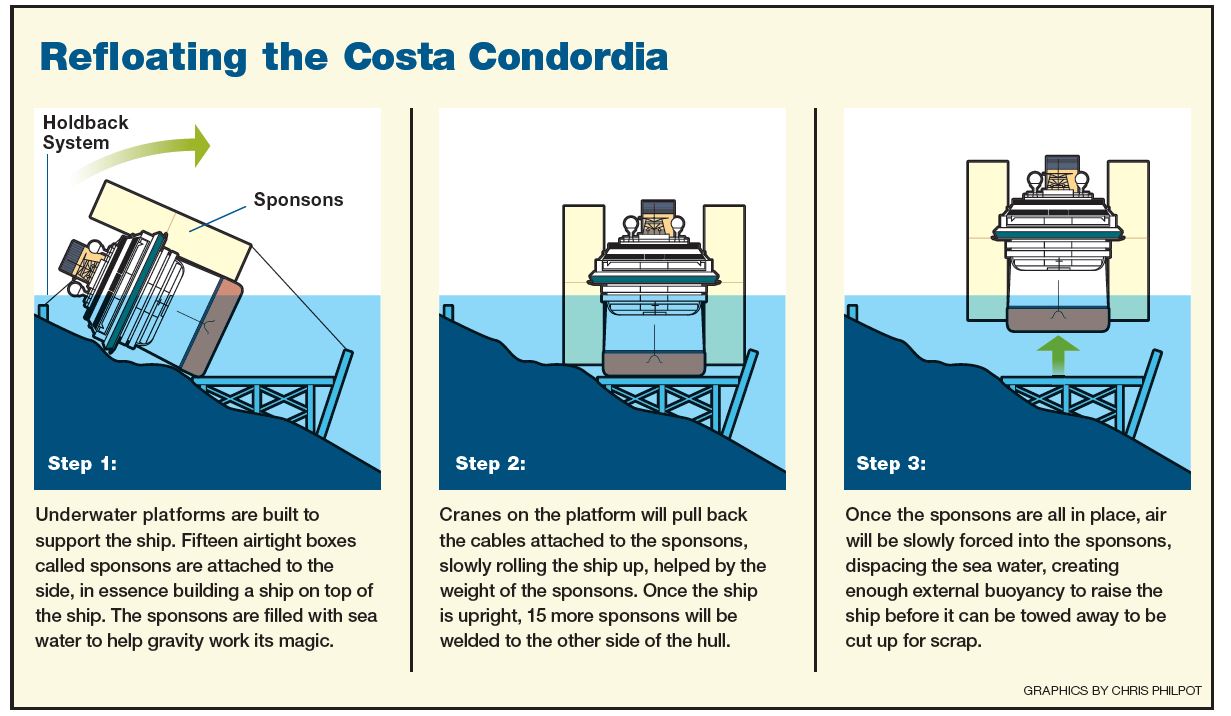

About 65 percent of the ship lies beneath the water, its interior almost completely flooded. Therefore, the ship can’t float on its own and it will need a stable floor to support it before it can be refloated. Titan and Micoperi constructed a six-part subsea platform, aligned precisely so that the Concordia will land squarely on it once its rotation is complete.

Simultaneously, enormous airtight boxes called sponsons are being welded to the exposed side of the ship. The 15 sponsons, most around 10 stories high and weighing up to 500 tons, will be filled with seawater initially. They will act as a cantilever, adding weight and assisting in the rotation.

The main event — the parbuckle — will be a slow and tense operation, lasting at least two days. With a network of strong cables, the team must apply enough force to rotate the vessel, while being careful not to put too much stress on the hull.

“There are a couple of big assumptions you’ve got to make,” explained Capt. Rich Habib, vice president and managing director of Titan Salvage.

“The amount of force you have to apply depends on the weight of the thing you’re going to rotate, where it’s going to pivot, and the center of gravity. It’s a simple physics problem if you knew all of the variables … but you don’t always know.”

The more force, the more risk. And for a ship that’s been languishing in the water this long, the risks are intensified. The Concordia’s hull is now covered in rust and is significantly weaker than it was 20 months ago.

“The water that it’s in is relatively warm temperature and that leads to more rapid corrosion,” said LIU’s Weiss. “The hull integrity of the vessel would become even more compromised.”

There’s no question that the parbuckling will be a nail-biter of an event. The ship is already in a stressed condition, lying in a position that the designers didn’t intend it for, said Habib.

“Now I’m going to add force to it. So I’m going to have a lot of distortions and things breaking and popping and so forth. It’s not a clean operation.”

After the ship has been rotated, most of it will be underwater. A matching set of 15 sponsons will be welded to the other side of the ship.

Hydraulic pumps will be used to force the seawater out of the sponsons and fill them with air, displacing water to create enough external buoyancy to lift the ship.

Slowly, the Costa Concordia will rise. But even then, a high degree of risk remains. The “what ifs” abound, said Michael Brown, area executive vice president, Marine, at Arthur J. Gallagher and Co.

“The wreck could slide off the table while they try to pump air into the sponsons, or a sponson could fail or come loose, and it could sink.”

If that were to happen in deep water, some might consider it a blessing. But if it re-sank in shallow water, it would be a whole new ball game.

Either way, this operation is getting expensive, very expensive.

“With a lot of salvage events, the contract is bid with a [fixed] number. In a situation like this, it’s an open ended cost — there’s not an upper limit on it,” said Weiss.

“Because of the restrictions being placed by the government, the bottom line is they’ve got to remove the wreck. It doesn’t matter how much it costs, they’ve got to get it out of there.”

Salvors will continue to attempt the removal of the wreck until the limits of liability of the clubs is reached, said Brown.

And there’s the rub: “It’s an interesting fact that P&I clubs usually write vessels with unlimited liability except in the case of pollution,” said Brown. “So we’re talking mega potential loss. It could get worse or it could start all over again.”

The Titan-Micoperi plan has been vetted repeatedly, but challenges, or worse, surprises, may remain.

“We refloat things all the time, but we may not know the extent of the damage 100 percent beforehand so we have risk there too,” said Habib.

The team will have people and equipment in place “to ensure that once we float it, we can hold it.”

A Foundation That Flexes to Fit

Every salvage project, from a small capsized craft to a shipwrecked luxury cruise liner, carries its own unique circumstances and set of risks. Salvors need to rely on insurance programs that allow them to adapt to whatever comes their way.

Titan Salvage executives are keenly aware that their insurance program is the difference maker, giving the company the security it needs to operate in a risky industry. But it goes deeper than that. A dynamic insurance program gives salvors the freedom they need to be able to bid on any project quickly. It also becomes part of the overall value that the salvor has to offer its clients. Habib said the strength of the company’s insurance program helps set Titan apart.

“My insurance covers are not a cost to me; they’re a tool that I use to do my business. My underwriters are my partners,” said Habib.

Dwight Menard is vice president, risk management for Crowley Maritime Corp., the parent company of Titan Salvage.

“Crowley relies heavily on its core insurance program that is both well established, but also very flexible,” said Menard. “It has the ability to quickly respond to either a $1,000 job or a multimillion dollar job. Salvors’ insurance is a different animal — it’s unique and very specialized.”

Salvors’ protection and indemnity coverage must be broadly worded to cover regularly assigned employees as well as additional crew that may be hired for any given job. It also has to adapt to the intricacies of employment classifications.

“Salvage jobs may occur anywhere in the world, so you could have jurisdictional issues — are salvage workers seamen? Are they considered longshore and harbor workers? Or do they fall under a foreign employment scheme for injuries on the job? The P&I coverage for the salvage crew is extremely broad and allows the flexibility to cover any of those scenarios should an injury occur on a salvage job. It’s a very unique but absolutely essential type of cover for us.”

Salvors’ liability covers the operations of the salvor while undertaking the salvage project. In a situation like the Costa Concordia’s, where the vessel has already been declared a constructive total loss, the issue of damage to the vessel is moot. But a salvor still requires cover for damage to third parties, or any legal damages that may occur as a result of the operations of removing the wreck.

“Usually those types of covers are obtained at relatively low limits — low levels being $5 million — for a primary layer,” explained Menard. “So, in addition we have a very well structured bumbershoot and excess liability program to conceivably respond to much larger exposures and liabilities.”

Large scale salvage projects tend to be equipment intensive, but it’s not always possible to have equipment readily available when incidents occur in isolated parts of the world. That’s why some salvors find it more prudent to lease equipment locally, which typically means the salvor will have to provide cover for any physical damage to the equipment — some of it highly specialized as well as high priced.

Menard said that Crowley uses a captive to manage much of its equipment exposure.

“That’s included in the type of risk that we either self insure in the captive, or else cover through reinsurance for values in excess of aggregate deductibles. If it’s an extraordinarily high risk or an unusual piece of equipment, then specialized cover might be the best method of dealing with it. But for the most part, we’re able to cover these exposures through our captive and reinsurance program.”

Size in Perspective

The meter is still running on the financial toll of the Concordia wreck.

The ship’s safe removal remains the concern of The Standard Club and The Steamship Mutual, the lead P&I insurers for the ship, and the rest of the clubs in the International Group of P&I Clubs.

The vessel is reinsured through the International Group’s pooling system and reinsurance program with the London and international reinsurance markets. Costs from intense governmental oversight and the engineering required to safely remove the ship from the reef have pushed the P&I loss reserve to $1.17 billion.

Such eye-popping numbers for the wreck of a single ship have left some questioning whether marine vessels are simply getting too big — big enough for underwriters to start asking at what point a vessel is too risky to insure.

The Costa Concordia, put in service in 2006, was the first of five Concordia-class vessels, built for $570 million and measuring in at 114,500 GT (gross tonnage). But the Concordia’s sister ships are no longer the biggest behemoths afloat. Costa launched the Carnival Dream in 2009, a $741 million, 128,000 GT vessel. There are three Dream-class vessels currently in service, and a fourth 132,500 GT vessel being built.

But of course, the bigger they are, the harder they fall. Or sink, as the case may be.

It seems logical to ask if there might be a tipping point — the point at which the size of the vessel would make a salvage operation so expensive that insuring it would become too big a risk.

“It’s a valid question,” said Tim Donney, global head of Allianz Risk Consulting, Marine. “The truth is the international maritime salvage industry may not be able to keep up with the requirements of disasters such as the Costa Concordia.”

But Titan’s Habib is circumspect on the subject. Contrary to what the perception may be about the Concordia, he said, the project is actually moving at a brisk pace.

“Here, you have the largest passenger vessel in history, by weight — the largest salvage job ever accomplished, and we’re ready to parbuckle it in 14 months. I could name 10 projects that went on for two years or more — five years in one case — and you wouldn’t know one of those names if I rattled them off. There’s this perception that these large vessels are vastly more complex in the way that they have to be done. But it’s still a salvage job and it still has all the risks and variables of floating a 600-foot tanker.”

Bigger doesn’t necessarily change the equation, said Habib. Projects are more expensive for a variety of reasons — and they’re not all related to size.

“The salvor’s tool bag hasn’t changed much over the years,” he said. “What we’re doing on [the Concordia] is bigger than what’s been done before, but we’re using standard techniques. It’s really the requirements being placed on us from the outside that are driving the costs up.

“There’s a spotlight on the job, and that brings to bear all kinds of complications. The bigger the job, the more that’s perceived to be at stake, the more the underwriters and the consultants and the authorities want certainty. That drives the price up exponentially. Certainty comes at a pretty high price in salvage.”

Barring unforeseen disruptions, the Concordia will be parbuckled in late September. Any delay at this point could hurt the odds of a successful removal.

“The longer the job goes on, the greater the risk,” said Habib. “Time is our enemy. Always is, always has been, always will be.”