Medical Management

No Consensus on Treatment

Even as the nation’s 50 states inch towards consistency in medical treatment guidelines for workers’ compensation injuries, there is no consensus on the role of risk managers in enforcing them.

Dr. Robert Goldberg, chief medical officer, Healthesystems, a national workers’ compensation benefits management provider, said risk managers should delegate oversight of treatment guidelines and compliance to those for whom it is a core competency.

“Why should risk managers know anything about treatment guidelines?” he asked.

“Management of care is in the capable hands of physicians, nurse case managers, insurers, TPAs (third-party administrators) and utilization review (UR) organizations.”

Anne Kirby, chief compliance officer and vice president of care management, Rising Medical Solutions

Anne Kirby, chief compliance officer and vice president of care management, Rising Medical Solutions, said it’s impractical for risk managers, with their myriad tasks, to also take on micromanagement of thousands of pages of treatment guidelines.

For example, ODG’s treatment guidelines — the most widely used — include 46 pages related to opiod usage.

“It’s too much for any single risk manager to know.” Instead, she advised risk managers to “do due diligence on the UR company.”

Ettie Schoor, president, Prism Consultants, said, however, that risk managers shouldn’t offload responsibility for enforcement onto their TPAs or carriers because of the risk of errors. She noted that TPAs have a lot of turnover, carriers are always hiring new adjusters, and both have very high caseloads.

2017 Power Broker® Dennis Tierney, a senior vice president in Marsh’s claim practice, said that risk managers should “have some familiarity” with guidelines for the body parts where their exposures are highest, as well as rely on the expertise of their TPA, carrier and broker claims consultant partners.

“Should risk managers be aware of guidelines?” asked Mary O’Donoghue, chief clinical and product officer, MedRisk. “Absolutely. Should they expect TPAs to administer medical review appropriately? Absolutely.”

She advised risk managers to focus their attention on unusually long, complex and expensive claims.

Many states and a few Canadian provinces have adopted, adapted or developed medical, surgical, therapeutic and pharmaceutical treatment guidelines for a number of workers’ compensation maladies.

The most common claims, according to The National Law Review, are strains and sprains (30 percent), cuts or punctures (19 percent), contusions (12 percent), inflammation (5 percent) and fractures (5 percent).

Do Treatment Guidelines Work?

The cautious consensus is that, overall, treatment guidelines usually work.

“In states where care is managed and guided using excellent guidelines and strong utilization, workplace injuries may be handled at a higher level of care with a higher expectation of recovery,” said Goldberg.

And in states with limited or no guidelines, “injuries may linger and lead to longer disability, higher indemnity payments and loss of return-to-work,” he said.

The extensiveness of treatment guidelines make it “too much for any single risk manager to know.” — Anne Kirby, chief compliance officer and vice president of care management, Rising Medical Solutions

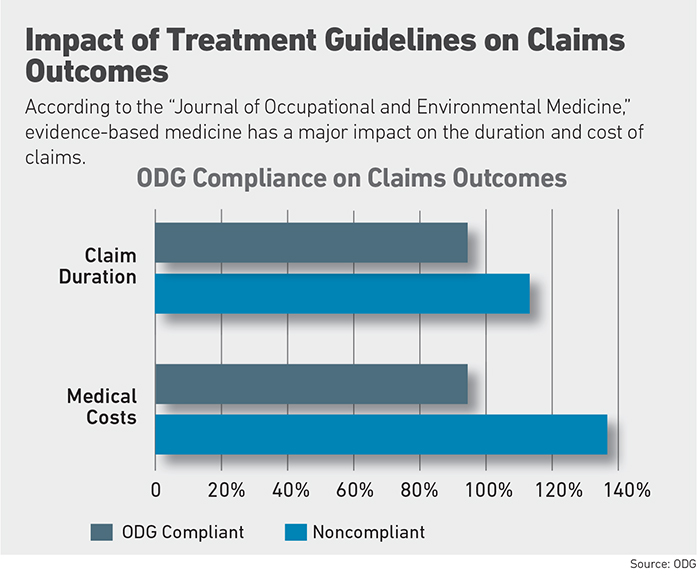

ODG points to statistics proving the effectiveness of guidelines.

States that adopted ODG guidelines, its website claimed, reported medical cost savings of 25 percent to 60 percent, average disability duration reduced from 34 percent to 66 percent, treatment delays from date of injury to initial treatment reduced 77 percent and insurance premiums reduced by 40 percent to 49 percent.

Only 13 states have no guidelines or none under consideration by the state legislatures, according to ODG.

Phil LeFevre, managing director, ODG, draws a bright line separating consensus-based guidelines characteristic to states that develop their own, and evidence-based guidelines “developed from comprehensive review of the medical literature, ranking and weighting thousands of studies based on design and quality, and tested for 15 years for optimal outcomes.”

A few states’ guidelines are mandatory — California and New York require compliance for certain injuries to most body parts, for example — but most are “guiderails” to keep treatment on track, said Goldberg of Healthesystems.

Some states adopt ODG and American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) guidelines, others develop their own, and yet others borrow from all of the above.

“Treatment guidelines give workers what they need, not what they want,” said Schoor. That brings a much-needed halt to excessive treatments that jack up medical and indemnity costs, she said.

Complex Cases Challenge Guidelines

Actual medical outcomes and return-to-work rates fall short of the promise of treatment guidelines, wrote Michael Gruber, partner, Pasternack Tilker Ziegler Walsh Stanton & Romano, LLP, a New York workers’ compensation law firm.

“ ‘Cookbook’ treatment rules effectively tie the hands of medical providers by not allowing them to use their judgment as to what treatment would be most beneficial for their patients,” he wrote in a newsletter for the American Association for Justice.

Most treatment guidelines are “pretty good” at predicting the medical treatment and return-to-work date of average claims, said Dr. Brian O’Malley, president, The Rehab Center in Charlotte, N.C., which treats complex worker injuries.

They’re not as good at guiding treatment for the outlying cases, which usually account for the largest expenditures, O’Malley said. “Guidelines may have a myopic view of an injury.”

For example, he said, most workers with a lumbar strain will return to work within 30 days. What happens to those who don’t?

“Decompression in the spine, spinal fusion, the condition deteriorates. The patient gets a spinal cord stimulator” — a highly dubious medical treatment in the workers’ compensation population, O’Malley said.

“Those end up costing the most money.”

Even with those lumbar strains that don’t lead to surgery, complex symptoms may follow: disturbed sleep due to pain, weight gain from inactivity, anxiety from disrupted routine and depression from isolation.

“It goes on and on,” O’Malley said.

“Many injuries need involvement by more than a spine specialist,” he said, including the emotional piece. Not all states compensate for mental health services.

Risk managers should “have some familiarity with guidelines for the body parts where their exposures are highest.” — Dennis Tierney, senior vice president and director, workers’ compensation, Marsh claim practice

Denied treatment prompts some injured workers to file claims under their private insurance or to pay for treatment out of pocket, Gruber wrote.

On the contrary, said Goldberg, the workers’ comp system is more prone to excessive care than denial of treatment.

Guidelines are designed to be flexible, permitting discretion for the treating physician, with room to file an appeal for denied treatment, said LeFevre.

Despite the good intentions behind guidelines, implementation can go awry, said Bernie Baltaxe, partner, Smith & Baltaxe, LLP, which specializes in workers’ compensation cases.

For example, a case now in the California Supreme Court alleges a UR doctor’s decision to decertify the sedative Klonopin in accordance with treatment guidelines led to seizures and additional injury. Klonopin was prescribed for anxiety related to a back injury.

Most guidelines are not mandatory, said Dr. Robert Hall, corporate medical director, workers’ comp division of Optum, but establish a starting point for treatment.

“If the current treatment plan isn’t working, there may be a good reason to deviate.”

If evidence points irrefutably to the optimal type and length of treatment for, say, a rotator cuff injury, why aren’t treatment guidelines the same across the country?

Inconsistent State Guidelines

“It boils down to the character of the state,” said Brian Allen, vice president, government affairs, workers’ comp division of Optum. “The handful of states that defer to market solutions tend to target specific conditions.”

Some years ago, for example, “every time you turned around in Montana you saw another back surgery,” which is highly controversial because of cost and efficacy. Treatment guidelines brought the number down 70 percent.

States that seek solutions from regulations, such as Massachusetts, have “sweeping guidelines covering a gamut of treatments.”

The lack of uniformity inhibits consistent medical care, said O’Donoghue of MedRisk.

“Treatment guidelines give workers what they need, not what they want.” — Ettie Schoor, president, Prism Consultants

“Some states have a presumption of treatment” rather than mandatory protocols, said Tron Emptage, chief clinical officer, workers’ comp division of Optum, which can be the deciding factor in a dispute over compensability between the payer and treating physician.

“If the doctor presents evidence for deviation from the guidelines, generally the payer will help determine coverage for the expense under the claim,” Emptage said.

Different states have different recommendations for treating lower back pain, which accounts for one-third of occupational musculoskeletal injuries and illnesses resulting in work disability, according to the Department of Labor.

“Some doctors order an x-ray at the first visit,” said Hall of Optum. Without accompanying red flags, such as fever or weight loss indicating a more severe underlying condition, “imaging has low value because the worker hasn’t had a chance to heal. Guidelines can keep the treatment on track.” &