The Law

Legal Spotlight

Duty of Defense Rejected

In 2011, Bryan Brettin, an orthodontist in Hudson, Wis., used a neighbor’s computer to pose as an unhappy patient of a competing dental practice.

Using the screen name “Hockey Mom,” whose son purportedly had oral surgery and braces, Brettin warned others about St. Croix Valley Dental: “Buyer beware.”

Using the screen name “Hockey Mom,” whose son purportedly had oral surgery and braces, Brettin warned others about St. Croix Valley Dental: “Buyer beware.”

In 2012, Brettin, his employer Daniel Sletten, and Sletten & Brettin Orthodontics (S&B) were sued by Douglas Wolf, a dentist at St. Croix, for defamation and libel, civil conspiracy and unfair competition.

Brettin, Sletten and S&B requested a defense from Continental Casualty Co., from which they had purchased general liability and personal liability coverage. They later added Wells Fargo Insurance Services to the case, as S&B was never added to the policy as a named insured.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota dismissed the case, ruling that the policy excluded coverage for acts done with the intent to injure. It declined to address the issue of whether S&B should have been a named insured, since there was no duty to defend.

On March 19, the U.S. 8th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that ruling, dismissing the dentists’ argument that the coverage was ambiguous because it provided coverage for defamation but also precluded it by defining an occurrence as an accident, and including an intent-to-injure exclusion.

The court ruled, however, that the two provisions “are opposite sides of the same coin,” and noted that it was possible to defame someone without intent to injure.

Scorecard: Continental Casualty did not need to provide a defense for the dentists or their dental practice.

Takeaway: Excluding coverage for intentional acts is designed to eliminate an “insured’s ability to cause harm intentionally with impunity.”

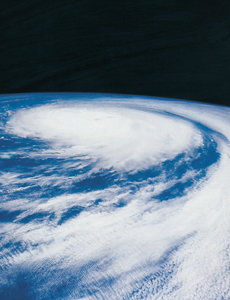

Hurricane Damage Partially Covered

In September 2005, Hurricane Rita struck along the Louisiana coast, bending the H-2 offshore well owned by Prime Natural Resources about 7 feet above the mud line, toppling the adjacent H-platform away from the well, and damaging the pipeline that attached the well and platform to a nearby facility.

Restoring the well to a pre-loss condition cost about $17 million, and about $4 million was spent on “debris removal and the rebuilding” of the platform, according to court documents.

Restoring the well to a pre-loss condition cost about $17 million, and about $4 million was spent on “debris removal and the rebuilding” of the platform, according to court documents.

Prime sought coverage from policies issued by a group of Lloyd’s of London syndicates and Navigators Insurance Co. UK, asking for all costs to restore the well and getting it back into production.

The underwriters declared the H-platform “to be a constructive total loss,” and paid Prime $900,000 for its 50 percent interest in the platform’s replacement cost value, according to legal documents.

The insurers also paid Prime $225,000 (25 percent of the replacement cost value) for debris removal from the platform and $2.88 million for claims related to pipeline damage and debris removal, and well-redrill operations. That was the maximum amount recoverable, they said.

Arguing that its total expenses were “unambiguously covered” by its policy, Prime sued the insurers in Texas District Court for breach of contract. The court dismissed the case.

On appeal to the Court of Appeals for the First District of Texas, the underwriters again prevailed, as the court ruled on March 26 that the contested portions of the policy covered wells and costs to regain control of wells “which get out of control,” but not to restore the wells.

It also ruled that the policy conditions related to physical damage to the platform included removal of debris and not restoring it to its pre-damage state, disagreeing with Prime’s argument that restoration of the platform was necessary to restore the well to production.

Scorecard: The insurers did not have to pay $4.7 million for breach of contract, lost business opportunities, lost profits or attorneys’ fees.

Takeaway: Prime’s costs to refurbish the platform were not accepted as “proactive” efforts to prevent the well from getting out of control.

Insurer on Hook for Cargo Damage

On Dec. 22, 2006, a train derailment near Newberry Springs, Calif., damaged cargo that was being shipped from Ohio and Indiana to Australia.

A.P. MollerMaersk, which had agreed to transport the goods on a single shipping contract that covered the entire journey, had subcontracted with BNSF Railway Co. to transport the cargo by rail from Illinois to California, where it was to be loaded on a Maersk ship for the ocean voyage to Australia.

A.P. MollerMaersk, which had agreed to transport the goods on a single shipping contract that covered the entire journey, had subcontracted with BNSF Railway Co. to transport the cargo by rail from Illinois to California, where it was to be loaded on a Maersk ship for the ocean voyage to Australia.

American Home Assurance Co. sued Maersk seeking to recover damages to the cargo, and Maersk sought indemnification from BNSF.

In 2011, a U.S. District Court ruled the Carmack Amendment, which covers liability of carriers under bills of lading, was the governing rule affecting the inland leg of the shipment, and in 2014, a court granted Maersk’s motion for a summary judgment.

American Home appealed. It argued that Maersk “assumed entire responsibility for the transportation of the cargo, and thus placed itself in the position that BNSF would have been had BNSF contracted directly” with the insurer.

The U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on March 25 that the lower court had properly interpreted the Carmack Amendment to determine that Maersk “is neither a rail carrier nor a freight forwarder and that Maersk did not agree to liability” under that amendment.

It also ruled that American Home could not argue the case on a contract claim, while on appeal, when previously it argued based on the Carmack Amendment.

Scorecard: The insurer could not recover damages from the ocean line.

Takeaway: Because American Home previously argued that the Carmack Amendment was the governing rule of the case, it had waived its right to later change to a contract-based argument.