Space Tourism

Forging into the Final Frontier

Imagine if a flight from London to Sydney took a mere two hours instead of 21. And imagine that on that flight, passengers could experience the same breathtaking views and feeling of weightlessness usually reserved for astronauts.

These are the possibilities presented by suborbital space flight, in which an aircraft gets outside of the Earth’s atmosphere, traveling at speeds up to 5,600 miles per hour. At this altitude and speed, an aircraft would follow a parabolic flight pattern, eventually falling back through the atmosphere. By comparison, an aircraft in orbital space would have to maintain speeds of about 17,500 miles per hour at an altitude of at least 190 miles above sea level.

Imagine if the destination were space itself. Or the International Space Station (ISS) or the Russian space station Mir, or even a hotel suspended hundreds of miles above Earth. Private space tourism companies have been working toward launching such flights since the 1980s.

American businessman Dennis Tito became the first private citizen to take a tour of space, doling out a reported $20 million for a ticket to ISS in 2001. Others followed. Space Adventures, a Virginia-based space tourism company, has already flown seven tourists — including Tito — to ISS on eight different occasions.

While frequency of manned spaceflights dropped off in the mid-2000s, research and development has rekindled demand. Paid commercial flights are expected to be launching around the globe beginning as soon as the end of this year.

A New York Times report on space tourism.

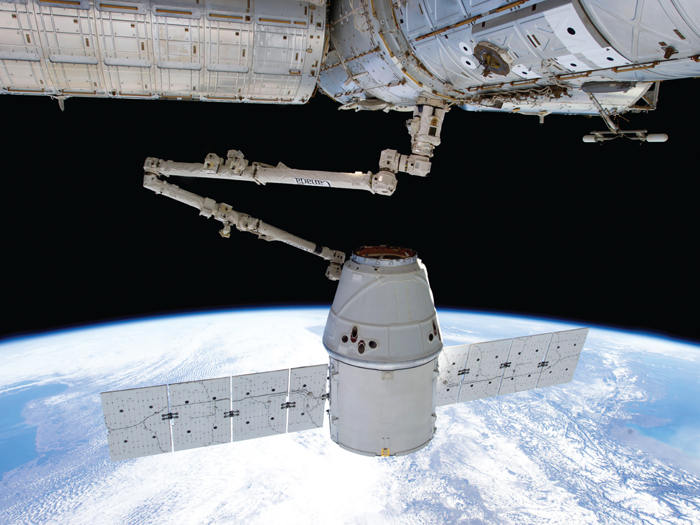

NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) also have a stake in this industry, as commercial space flights can be used to deliver cargo to space stations. The California-based company SpaceX is contracted with NASA to make 12 cargo resupply trips to ISS through 2016. They completed the first successfully in 2012.

These endeavors could be stalled, though, if space flight providers cannot obtain the right coverage to insure against third-party liability risks and property damage.

Third-Party Liability

The role of insurance in allowing the space tourism industry to grow is “huge,” according to Bill Behan, CEO of AirSure Ltd., an insurance and risk management consulting company for the aviation industry.

“The financing, investment, stability and future of the commercial space industry will depend on a strong and enduring partnership with the insurance industry,” he said.

The federal government forged that relationship and fostered industry growth with the passage of the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984 (CSLA). The CSLA provides a framework for the FAA to regulate companies by granting launch licenses as well as indemnifying launch providers from third-party claims. The indemnification provision requires companies to buy insurance coverage for third-party liability claims at a level calculated by the FAA, called the “maximum probable loss.”

Should an accident occur, the government would be liable for losses exceeding that level up to a limit of roughly $2.7 billion, though that limit is adjusted every year for inflation.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO), however, thinks that the FAA’s methodology for calculating maximum probable loss is flawed. Currently, the administration estimates the cost of a single casualty at $3 million, a figure that has not been updated since 1988. In calculating total loss value, the FAA adds 50 percent of the total cost of casualties for a given flight to account for potential property damage.

It arrives at an estimated number of third-party casualties by identifying areas that could be impacted by lethal debris, and then multiplying the size of the area by the probability of damage occurring there and the population density.

Risk modelers consulted for the GAO report “stated that FAA’s method might significantly understate the number of potential casualties, noting that an event that has a less than 1 in 10 million chance of occurring is likely to involve significantly more casualties than predicted under FAA’s approach.”

The FAA’s equation does not always consider details like an aircraft’s flight dynamics or the characteristics of its materials. Nor does it specifically analyze how many properties could be damaged by an event or what the value of that property might be.

If the FAA underestimates maximum probable loss, it means commercial space companies will purchase inadequate levels of insurance, exposing the government to more liability. The GAO recommended that the FAA regularly review its methodology and make amendments to the CSLA to better prepare for potential catastrophe, but so far no changes have been made.

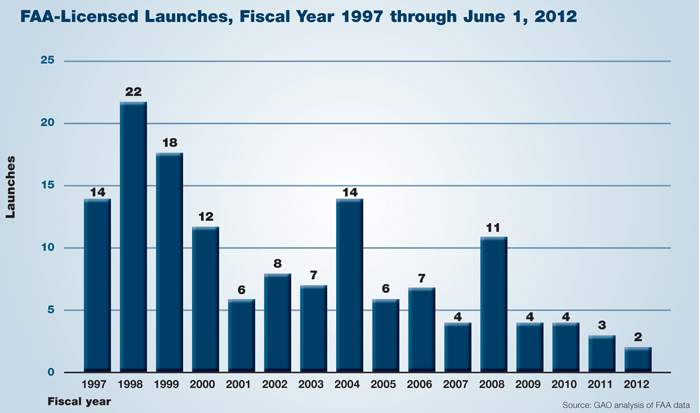

That could spell big trouble for the space industry, especially with the number of FAA-licensed space launches expected to grow substantially over the next few years. NASA expects to launch at least two cargo resupply trips to ISS per year from 2017 to 2020, and that doesn’t include the stargazing adventures in the works from Virgin Galactic and its competitors. A tragedy not adequately insured could have the potential to wipe out the sector, or at least set it back many years.

Informed Consent

Flight operators also need to worry about the safety of passengers and crew on board.

Companies and state legislatures require passengers to sign informed consent waivers, relieving companies from liability if an accident causes injury or death. But are the waivers strong enough to stand up in court?

“Informed consent is about giving the space flight participant enough technical knowledge to understand and appreciate the risks involved,” said Clive Smith, business unit leader with Aon’s International Space Brokers.

However, given the likely volume of space flight participants in the coming years, it’s safe to say that the protection of informed consent waivers remains to be tested.

There’s also no escaping the fact that a participant willing to pay a for trip to space can afford top lawyers and high legal fees in the event of a serious injury in the course of a flight.

“Stay tuned for creative plaintiffs’ lawyers who will challenge any contractual language laws because of the money involved.”

“Stay tuned for creative plaintiffs’ lawyers who will challenge any contractual language laws because of the money involved,” said Behan.

The laws could, however, make it easier for space tourism companies to attract insurers.

“Any laws that might protect space companies or manufacturers may facilitate broader terms and lower premiums for liability insurance,” said Esequiel Nathal, an analyst with Charles Taylor Risk Consulting.

Several states have adopted informed consent laws — including New Mexico, Virginia, Texas, Florida, Colorado and California — but they vary in their levels of protection. For instance, most statutes protect only the launch company and not their suppliers or manufacturers.

The lack of loss history in human spaceflight makes it difficult to determine the usefulness of the waivers, a problem that extends to all areas of space tourism.

Insurance and Risk Management

Insuring human spaceflight means navigating through lots of gray area, with little data and lots of faith. For instance, would a hull policy covering a spacecraft be dependent on whether it is bound for orbital or suborbital flight? Does it matter where in airspace an accident occurs? Would coverage fall under the realm of aviation or space flight insurance?

The answer to most of these questions: to be determined. Too few manned spaceflights have been launched and too few accidents have occurred to reveal weak spots in coverage.

“The debate really is whether the risks are covered under the aviation market or the space market, because they’re two different kinds of market although there’s some crossover in terms of the insurers,” Smith said.

“There will be lots of challenges as to whether the space market can pick up the aviation style of cover or whether part of it is placed in the aviation market and part in the space market.”

“This is specialized insurance normally requiring a specialized insurer and broker,” Nathal said. Underwriters must mostly rely on alternate data “in the form of successful private launch of satellites and other forms of transportation and safe operation.”

Luckily, space tourism companies are generally well-funded and can handle the high premiums that intrepid insurers will charge.

“More importantly, it is essential to conduct thorough risk assessments to understand what the risks are, their size and nature, and the best ways to mitigate the risks,” Nathal said.

“Insurance coverage is not a substitute for robust risk mitigation. Remember NASA’s motto: ‘Failure is not an option.’ ”

“Insurance coverage is not a substitute for robust risk mitigation. Remember NASA’s motto: ‘Failure is not an option.’ ”

Risk management includes not only educating passengers on flight risks, but also training them properly. While training for private citizens is nowhere near as rigorous as what astronauts receive, it should still include some time in “g-force” and exposure to a weightless environment. Again, only time and experience will show what level of training is best to ensure safety of passengers and crew alike.

Sending more manned missions to space opens up a wealth of opportunities for scientific advancement and the development of a brand new industry. But the risks involved are literally sky high.

Moving safely ahead demands innovation, flexibility and cooperation from all involved, from the FAA to launch companies to insurers willing to underwrite the unknowns of the final frontier.