Compliance Risk

Caught in the Middle

In June 2015, SFX Financial Advisory and Management Enterprises, a subsidiary of Live Nation, fired Brian Ourand, the company’s president.

A few years earlier, Eugene Mason, chief compliance officer of SFX, suspected Ourand was stealing money from athletes who used the firm for investments and financial services. He promptly conducted an internal investigation and concluded that more than $650,000 was missing from three clients’ funds. Allegedly, one of them was former boxing champion Mike Tyson.

SFX reported the alleged theft to criminal authorities, and in December 2015, Ourand was arrested by the FBI. He is awaiting trial on the criminal charges.

In March 2016, Ourand was found guilty of embezzlement by an administrative law judge of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, who fined him $671,000 and barred him from the securities industry.

Mason’s reward for his efforts? In June 2015, he was officially censured by the SEC.

“SFX’s compliance policies and procedures were not reasonably designed, and were not effectively implemented, to prevent the misappropriation of client funds,” the SEC concluded, fining Mason $25,000 and fining SFX $150,000.

That was not the first time — and it probably won’t be the last — that the SEC decided that a chief compliance officer’s inadequate policies and procedures were at least partly responsible for an organization’s unethical or criminal behavior — even though the CCO was not involved in the wrongdoing.

Many CCOs in the financial services industry are aware of the potential liability they face and are wary.

Compliance officers in other industries, however, may be unaware of this potential liability, and it may be only a matter of time for other federal regulators to consider targeting CCOs when misconduct occurs.

Some experts speculate that the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the False Claims Act are two laws that might ensnare compliance officers in their position between wrongdoing companies and aggressive enforcement agencies.

“It’s a confluence of events that would make me nervous if I was a compliance officer.” — Jessica Flinn, senior vice president, Integro Insurance Brokers

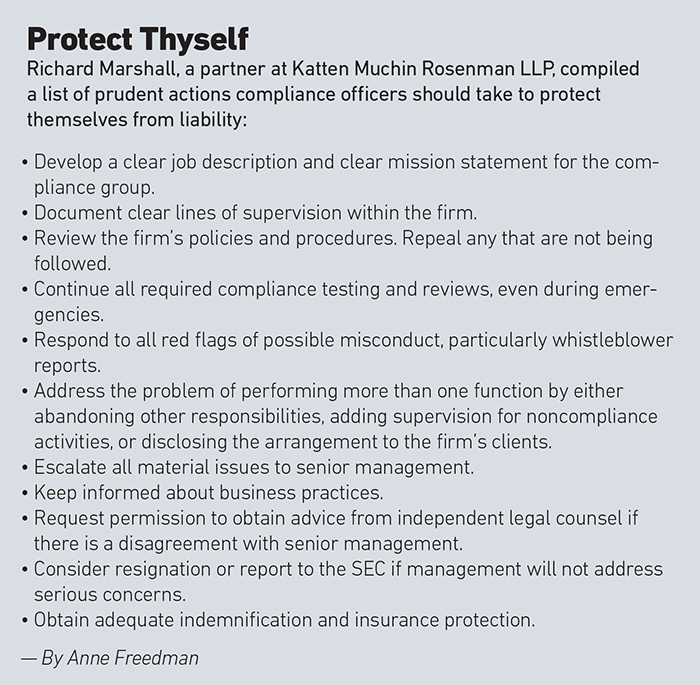

“There remains a high level of concern on the part of compliance officers,” said Richard D. Marshall, a partner at Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP. “I think this is spreading into other areas [than those in the SEC’s purview].

“Will this apply to a chief compliance officer at a cement company? It’s a different world. I think compliance there has a different meaning than in financial services,” he said.

But, health care may not be as far-fetched.

“If I would go out on a limb, I think health care [compliance officers have the potential to be targeted], mainly because of Medicare and Medicaid payments, and False Claims Act exposures,” said Jessica Flinn, senior vice president at Integro Insurance Brokers.

“Anything from a regulatory perspective where they can set their eyes on someone else, yes, I would be worried. … It’s a confluence of events that would make me nervous if I was a compliance officer,” she said.

As for the FCPA, Pat Harned, CEO of the nonprofit Ethics & Compliance Initiative, noted that the Department of Justice enacted a program to look at corporate ethics.

“I think there is every reason to think that the SEC won’t be the only agency to look at whether the ethics and compliance function is in place,” she said. “And if not, why not?”

The SEC’s action in the SFX Financial case and another involving BlackRock Advisors — where a CCO was fined $60,000 after a portfolio manager (who was not sanctioned) had a conflict of interest that the firm failed to disclose — prompted then-SEC Commissioner Daniel M. Gallagher to issue a statement criticizing the enforcement actions.

“Actions like these are undoubtedly sending a troubling message that CCOs should not take ownership of their firm’s compliance policies and procedures, lest they be held accountable for the conduct that … is the responsibility of the [financial] adviser itself,” he wrote in June 2015.

In the statement, Gallagher said the SEC was creating “perverse incentives … targeting compliance personnel who are willing to run into the fires that so often occur at regulated entities.”

“As it stands, the Commission seems to be cutting off the noses of CCOs to spite its face,” he said.

The National Society of Compliance Professionals is also troubled by the SEC’s second-guessing of compliance officers, “particularly where the obligation to execute those procedures rests with the business,” wrote Lisa D. Crossley, executive director of the society to the SEC’s director of enforcement.

Compliance officers, she wrote, could be investigated and face “potentially career-altering liability for simple mistakes or errors of judgment which could somehow be connected to a primary violation committed by others.”

Mark Weintraub, vice president, insurance and claims counsel, Lockton, said, “I know a lot of CCOs in particular are really afraid of this, and that they are going to find themselves second-guessed.”

“I don’t think [the SEC is] truly looking to catch CCOs unaware or play gotcha with them,” he said. “They really only want them to do their jobs.

“Ideally, a compliance officer should have policies and procedures in place to prevent [theft or conflicts of interest] and that did not happen in those enforcement actions,” he said.

The SEC’s actions are based on its interpretation of a “failure to supervise,” which has been extended to include compliance officers, Marshall said.

“The theory is you weren’t trying hard enough to prevent [the wrongdoing],” he said. “It has created a lot of concern.

“Unfortunately,” said Marshall, “it seems every couple of years, there is some controversy about this.”

The disconnect occurs because CCOs usually do not have the authority to stop misconduct on their own. They rely on corporate leaders to enforce and fund compliance programs.

“It turns the whole system on its head,” Marshall said. “Compliance helps companies that are well-intentioned to do the right thing so we want to support them so they are more likely to do the right thing.

“If you just whack people when something doesn’t get prevented, what incentives are you creating? It’s discouraging good people from being compliance officers,” he said.

“The theory seems to be that compliance is some insurance policy guaranteeing that nothing ever goes wrong. Therefore, if something goes wrong, the compliance system is defective,” Marshall said.

“That’s ridiculous.”

“There’s no question,” said Harned of the Ethics & Compliance Initiative, “that it’s getting harder to recruit chief compliance officers. You see it more in some industries than in others. It’s true in financial services in particular … because of the personal liability.”

Putting protection in place can be challenging, Lockton’s Weintraub said.

“These aren’t classic D&O cases,” he said.

Wrongful acts are generally covered under D&O, but if the CCO was “taken to task for failure to write a policy [as opposed to an overt action], coverage would depend on the allegation. It can be tricky,” he said.

The other hurdle will be the investigatory phase. Typically, coverage is triggered when an individual is named as part of the allegations, and that tends to happen at the very end of the investigation, Weintraub said.

“You can be paying your own bills for a while until the insurance coverage is triggered and comes to bear,” he said.

If the compliance officer is not covered under the D&O policy, the E&O policy would generally cover them, said Michael Klaschka, managing principal, EPIC Brokers & Consultants.

“As to which policy would apply, it would really depend on the claim itself,” he said. “Is it a claim alleging a wrongful act arising from professional services or in an officer-type capacity such as a breach of fiduciary duty? Either way, you have to make sure the wording is drafted correctly,” he said.

“I have definitely received phone calls from CCOs about this,” he said. “They want to know, ‘Am I covered? What should I be thinking about?’

“There are insurance products out there specifically for them but they usually require an underlying D&O or E&O contract. If the company has appropriate D&O or E&O cover, they should be fine. It’s just a question of whether the limits of liability are adequate.”

Even if a policy is triggered, fines and penalties are usually uninsurable. And criminal or fraudulent acts are generally excluded from coverage.

“If, in fact, they committed fraud, they will not be covered,” Klaschka said. “If someone else within the organization did, and the personal conduct exclusions in the D&O and E&O policy are crafted correctly, they will still have coverage.”

“If I were a CCO,” Weintraub said, “I would want more of a contract, an indemnity agreement, with the company to spell out what they would do for me to address this type of thing,” he said. “If I am fined for whatever reason or there is a settlement, if possible I would want to make my employer pay it.

“Insurance is really the last line of defense. The first line is corporate indemnity. You want to drive things there,” he said.

“If you just whack people when something doesn’t get prevented, what incentives are you creating?” — Richard D. Marshall, partner, Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP

Marshall said a compliance officer, who “was trying to do the right thing,” was sued last year after a person at his company committed wrongdoing, but there was no indemnification because the company went bankrupt and the individual possessed limited funds for his own defense.

“He ended up settling on very unfavorable terms. It was a very sad thing,” he said.

Best practices for policies and procedures are important, but consistent training and guidance are equally important, Klaschka said.

“You could have the best practice in the world; it’s making sure they are followed,” he said. “It’s like having a privacy policy on a website, everybody has access but are they following it? Are they reading it?”

CCOs should review the organizational reporting structure to better protect themselves, he said.

“The key is making sure there is a direct line to the board,” Klaschka said. “If the board is unwilling to make those decisions, they should leave the firm.”

“Unfortunately,” said Integrto’s Flinn, “many organizations don’t become proactive until there is an incident. The barn has to be burning until they spend the money. That’s a problem for many CCOs.” &