Health Care

Care to Be Continued

Last Oct. 1, The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) hit Dallas’ Baylor Health Care System with a new species of penalty: Too many of its heart patients bounced back into the hospital too soon after discharge. With 67 percent of hospitals nationally hit with similar penalties in 2012, Baylor had lots of company.

Botched patient hand-offs contribute to a high rate of readmissions, of which 76 percent are preventable, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Health care risk managers, beware.

Penalties for high rates of readmissions will rise over the next few years under the Readmissions Reduction Program of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a factor which is motivating insurers and health care providers to figure out how to improve their continuation of care practices.

Cutting Readmissions

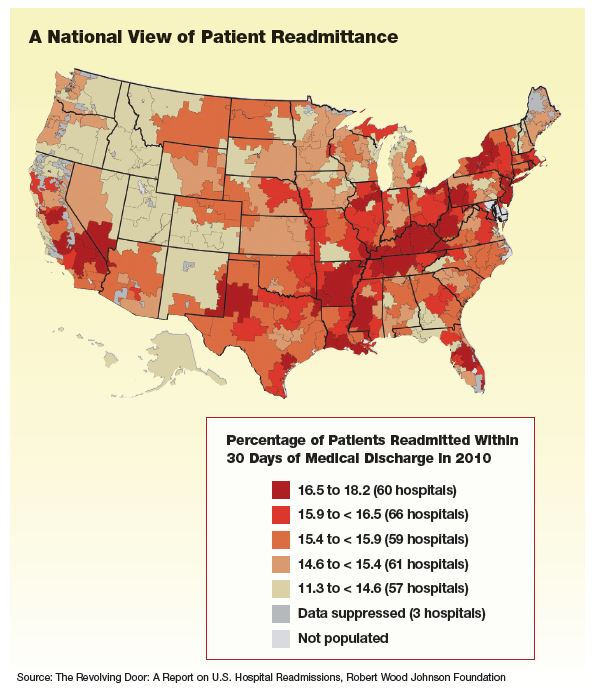

The good news is that with hospitals having been given advanced warning that they will be penalized, readmissions overall are already dropping. According to CMS, the readmissions rate for Medicare patients dropped to 17.8 percent at the end of 2012, down from a high of 19.5 percent during the previous five years.

Hospitals are using risk assessment tools, such as the Society of Hospital Medicine’s “8Ps” to identify patients who are at high risk for readmission: the 8Ps are Problem medications; Psychological issues; Positive screen for depression; Principal diagnosis; Polypharmacy (five or more routine medications); Poor health literacy: lack of Patient support; Prior hospitalization; and Palliative care.

Baylor is part of the trend to lower readmission rates. Its $4,500 penalty, while still a blemish, could have been as high as $7.5 million if the hospital hadn’t started corrective measures several years ago, said Dr. Cliff Fullerton, chief medical officer at Baylor Quality Alliance. With readmissions for its high-risk patients at 60 percent and CMS penalties looming, Baylor started to overhaul care coordination across its 14 hospitals, numerous physician groups and ancillary care facilities.

Baylor referred to the University of Pennsylvania’s Transitional Care Model (TMC) as it undertook the arduous and expensive process. TMC engages advanced practice nurses, social workers, family members and patients to close every imaginable gap in communication and post-discharge compliance, thus eliminating preventable hospital readmissions. Baylor developed its technology infrastructure, overhauled its go-it-alone culture, instituted a nurse-led discharge process and followed up with phone calls.

The effort paid off, Fullerton said. Combined readmissions among all risk groups dropped by half, with the high-risk group’s rates down from 60 percent to 25 percent. “We haven’t made any money from it, but we’re not risking more penalties. And it was the right thing to do.”

Philadelphia’s Nazareth Hospital automatically enrolls heart patients in “telehealth” programs, where they monitor their own heart rate, blood pressure and weight. A weight gain of two pounds, said Erin Donohue, a care transition nurse, would trigger a call from the telehealth company to the physician.

“They would ask, ‘How do you want us to intervene?’ ” she said, noting that such action may avert a readmission.

Although well-intended, even these programs have their problems, said Mary Cashman, a nurse at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. For complex cultural and psychological reasons, some patients don’t comply even when it’s free, easy and the consequences for noncompliance are dire.

Discussing a 30-year-old “frequent flyer” on dialysis, Cashman said, “We spend hours explaining the treatment plan, he has coupons for free meds, we send a nurse to his home and a van to take him to appointments, and still he’s back after two weeks. And we get dinged for a readmission.”

The National Quality Forum (NQF), a nonprofit dedicated to improving health care quality in the United States, performs “community health needs assessments.” These pinpoint interventions that bring noncompliant patients, such as substance abusers, indigents and the disenfranchised, into the medical care mainstream and thus avoid readmissions. “We meet patients where they’re at,” said Karen Adams, NQF vice president of national priorities.

Providers Get Wired

Well coordinated care depends on technology, much of which is mandated in the Obama administration’s effort to convert all medical records into an electronic format by 2014. New rules on using electronic health records (EHR) technology from the Department of Health and Human Services affect providers that receive incentive payments from Medicare and Medicaid.

Under the new rules, eligible providers must adopt EHR technology and demonstrate its “meaningful use.” The rules include patients’ online access to their health information and exchange of electronic health information between providers.

The unbroken access to EHR across the continuum of care will become yet more important when millions of uninsured Americans with no or lapsed medical records enter the system under the ACA’s individual mandate in January. It will also help tame the inevitable administrative tangles as the health care industry consolidates and institutions diversify, said Matt Mitchell, president of Hanover Healthcare, a health care specialty insurer.

Driven by the ACA’s cuts in Medicare reimbursements, health care institutions are acquiring other providers to achieve economies of scale and negotiation power with insurers and lenders, Mitchell said. Hospitals are forming Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which physicians join both to ensure a steady revenue stream and to meet the requirements for enhanced payments under Medicare. Skilled nursing facilities are broadening their services into independent and assisted living to decrease their dependence on Medicare reimbursements.

Physician groups are compelled to join ACOs, but they usually lack the resources to build them. Typically small businesses, medical practices can’t afford to build risk management systems or buy billing and EHR systems robust enough to support an ACO, said Jeff Brunken, president of The MGIS Cos. Inc., an insurer of doctors and hospitals. “Hospitals have the resources, so they build the ACO. And whoever builds it owns it.”

The ACOs’ emphasis on uniform protocol can be a bitter pill for doctors who are accustomed to autonomy, said Baylor’s Fullerton. However, the uniformity imposed on treatment protocols, nomenclature, and EHR and risk management systems appears to improve quality of care, said Jeff Driver, chief risk officer of Stanford University Medical Center.

“No matter where patients are seen in a network, they will use a common risk management and communication system,” Driver said, which reduces the opportunity for information “drops.” It also exposes incompatible drugs and other potential dangers that can result in readmissions.

Checking and re-checking data mitigates technology’s vulnerability to human error, said Carol Burkhart, senior vice president at Marsh/Global Healthcare Consulting. “It’s garbage in, garbage out,” she said. For example, if the primary care physician’s name is entered incorrectly when the patient record is opened, the wrong name may be autopopulated throughout the record’s life.

Accuracy requires redundancy of effort, but it’s effort well spent, Burkhart said, citing personal experience. Speaking from the hospital where her seven-month-old granddaughter had just undergone surgery to correct a congenital heart defect, Burkhart described a redundant backup medication reconciliation that prevented catastrophe at every juncture of the treatment.

“Even though a nurse and the physicians had reconciled her medications, a pharmacy resident came into pediatric ICU to again validate the medication reconciliation,” Burkhart said. “Front-end investment of redundancy saves hours of case managers’ rework on the back end.”

Despite advances in technology, systemic failures of coordinated care still happen, she said, such as a notorious case in which a patient stayed in observation status for 43 days, far exceeding the standard 24- to 48-hour diagnosis. “This total failure of care coordination called for a root cause analysis” by an interdisciplinary care team, Burkhart said, but the organization lacked even a defined process for flagging the event for analysis.

“The solution to high readmissions isn’t just technology,” Driver said. “It’s technology combined with really smart people to change processes. And then it’s re-measuring readmission rates to make sure they’re still declining.”

New Risks

The ACA’s new payment structures are creating a new set of insurance issues for doctors, hospitals and ancillary providers, said Brunken. That creates uncertainty in the absence of legal precedent.

For example, asked Hanover Healthcare’s Mitchell, in cases like Nazareth Hospital’s telehealth program, where is the provider licensed to do business? And when a patient uses a home infusion machine or a videoscreen for physical therapy, what is the appropriate insurance coverage?

ACOs, patient-centered health homes and other new delivery models introduce ways to hold providers accountable for providing quality care, said Brunken.

“As hospitals, doctors, and ancillary providers come together, they each need to understand how they’re protected, both as a group and as individuals.

For example, he said, if a van transporting a discharged patient to a follow-up appointment with a physician has an accident, he asked, will all participants in the ACO be liable? Will they all take on employment liability risks in credentialing and selecting partners?

“Get good advice,” said Mitchell. “Work with an agent who understands changes in the industry. As exposures change, institutions need an insurance program that changes with them.”