Worker Safety

Stretching Risk Management

Visit the offices of progressive, safety-minded construction companies these days and you’ll see each and every employee — management level and otherwise — stretching, bending and reaching before starting the workday.

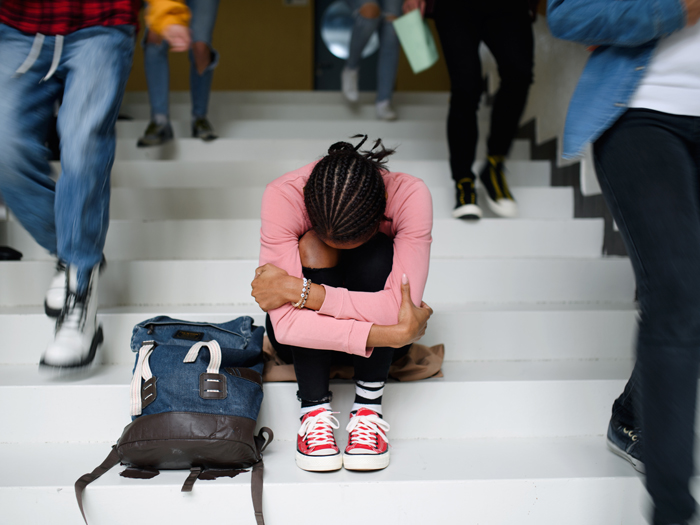

In an industry where strains and sprains are by far the most frequent and costly injuries — followed by falls, which are less common but more severe in terms of the damage — more and more construction professionals have adopted a “stretch and flex” regimen to minimize on-the-job hazards.

To protect their bottom lines, they need to. In some regions of the country, New York City in particular, some insurance carriers have found the workers’ compensation market for construction so troubling they have withdrawn from it altogether. Contractors have taken on more retentions and are much more vigilant about safety as a result.

A National Pain

Nationally, escalating medical costs and steadily increasing workers’ compensation premiums in construction (driven in part by low interest rates impacting insurer investment income) have conspired to make managers, supervisors and workers in the rough-and-tumble construction industry increasingly safety-conscious.

“If you’d told me 20 years ago construction companies would do this [adopt stretching programs], I’d say, ‘It won’t happen,’ ” said Kevin Clary, vice president of loss control for Amerisure Insurance Co., a major writer of workers’ compensation and business insurance specializing in manufacturing, construction and health care, based in Farmington Hills, Mich.

“We’ve been seeing [stretch and flex programs] more and more over the past eight years,” said Clary, noting that many of the largest national general contractors now require that employees at the jobsite engage in at least 10 to 20 minutes of stretching before starting work.

Loss control and safety measures are being increasingly employed in construction at a time when workers’ compensation rates continue to climb for this business, which is considered one of the most dangerous in the country.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), construction work is the 10th deadliest job in the country — not as bad as logging or fishing, which took the No. 1 and No. 2 spots. Construction is safer too, than farming, airline piloting and collecting recyclable waste.

Normally, severity of workers’ compensation claims in construction is about 50 percent higher than for all industries combined, the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI) said in 2012.

The organization also pointed out that recessionary factors leading to a decline in construction may have temporarily helped workers’ compensation medical costs lag behind the Medical Consumer Price Index (CPI) in 2010. However, the trend seems to have been short-lived.

By 2011, workers’ compensation average medical costs once again exceeded the Medical CPI, a measure that tracks price inflation for all forms of health care excluding utilization factors.

A Tight Spot for Insurance Buyers

Starting around 2008, construction jobs became more scarce and harder to bid on successfully.

Many construction companies began downsizing between 2008 and 2010, in particular, according to BLS data, which show construction industry employment peaking in 2006 and 2007, and dropping markedly in 2010 and 2011, before beginning a slow climb back up over the past two years.

At the same time there was increased competition for work in the sector, the workers’ compensation market for the construction industry was tightening, putting commercial insurance buyers in construction in a tight spot.

In many lines of insurance, low interest rates have put some pressure on premium rate to make up for lost investment income. Increasing medical inflation and continued claims severity for construction workers have also helped increase insurance rates, and industry experts said that the trend isn’t likely to abate anytime soon.

Many construction firms have faced workers’ compensation premium increases of roughly 5 percent to 30 percent each year for the past three to four years, experts said.

Construction classes tend to be more hazardous and more expensive from a premium standpoint, with minor exceptions in some states, said Henry Lombardi, global broking officer with Aon Risk Solutions’ Construction Services Group in New York.

“For example, here in New York, the October 2013 rate change does show some construction rates decreasing from last year but [the change is] very slight — less than 2 percent in most cases,” Lombardi said.

Overall, fatal injuries in the construction sector have gone down 37 percent since 2006, according to U.S. Labor Department statistics.

That trend is being driven by better safety equipment and improved work practices, said Ron Sokol, chief executive officer of the Safety Council of Texas City, Texas. But the economy has created a unique set of challenges.

New construction projects are finally beginning to pick up, so hiring is too. But the rebound comes at a price. Some said that the industry experienced a talent drain during the downturn, shrinking the pool of personnel that would oversee safety programs. The net result is a setback in the industry’s overall injury prevention efforts.

An August 2013 BLS report found that on-the-job fatalities in construction rose 5 percent, to 775 in 2012. That’s the first increase since before the financial crisis. The rise was also attributed in part to new home construction and the hiring of inexperienced workers.

Stretch and Flex Regimens Work

Regardless of economic trends, many construction risk managers have the ability to improve their workers’ compensation claims experience and reduce their rates by using safety initiatives like stretch and flex regimens, underwriters and brokers said.

Zurich stated in a recent report that, based on its experience with more than 100 companies implementing workplace stretching programs from 2007 through 2009, the underwriter saw an overall 61 percent reduction in strain/sprain frequency and a 30 percent reduction in strain/sprain severity. The report was authored by Patrick Clarke, Zurich Services Corp. risk engineering manager.

An earlier report from the University of Oregon in 2003 examined one flexibility program among municipal firefighters, finding that those who participated in the program were more flexible than nonstretchers after six months.

Two years after the Oregon study, researchers saw little difference in the number of injuries sustained by each group: a total of 48 among stretchers and 52 injuries among nonstretchers.

However, the dollars spent to address these injuries was staggeringly different for the two groups: $85,372 for stretchers versus $235,131 for nonstretchers.

A closer look showed that the more flexible group lost much less time from work, with medical costs for stretchers less than half that of nonstretchers: “A breakdown of costs revealed that time-loss costs for stretchers were significantly lower than for nonstretchers — $45,597 versus $147,581, respectively,” the Oregon report stated.

Medical costs were $39,775 for stretchers versus $87,550 for nonstretchers.

The study also suggested that those working with their hands should consider a combination of stretching and strength training.

One study examining progressive resistance strength training alone, and trunk flexibility stretches before and after strength training, found that flexibility improved only for the group performing strength training along with stretching. The study also cautioned against ballistic stretching, where an individual bounces the muscle he or she is stretching, since the practice has been shown to cause injury.

Other measures beside stretching and flexing that construction industry risk managers can adopt to reduce their workers’ comp exposures and hopefully their premium costs as well include:

• Ladders. Consider a no-ladder policy for subcontractors. “I think the no-ladder policy is cutting edge,” said Amerisure’s Clary.

“We’ve been seeing this now for the last couple of years; a lot of subcontractors will not work from ladders, using man-lifts instead to ascend to certain heights,” he said.

“Man-lifts from 4 to 20 feet are a safer option than ladders,” said Clary. “Over 20 feet, we recommend scaffolding.”

• Accountability. Another area where construction firms are not as progressive as they could be, said Clary, is in creating sufficient accountability for safety among managers and supervisors.

Production accountability has been well instilled by management, he said. Supervisors will move mountains to make required deadllines.

Reducing the number of injuries occurring on a particular job is often less of a priority, he said.

One way to change that, said Clary, is by including a supervisor’s safety record in his or her year-end performance review.

“A lot of companies could improve in this area,” said the loss control expert.

• Screening. Screening new employees can be a plus from a safety standpoint. “One of the big factors now in terms of increasing exposures is hiring selection and screening,” said Clary, noting that less experienced employees are more susceptible to injuries than experienced construction workers, many of whom lost their jobs during the economic downturn.

• Alternative Risk. Once a firm has implemented the right safety measures to improve their loss experience, it can consider alternative risk financing options such as taking a higher deductible or implementing “retro” programs, where insurance costs come down at the end of the policy year based on its safety record.

Those buyers with a good safety record will have a wider choice of insurance carriers, Clary said.

They will also attain a better experience modification rate (EMR), said Aon Risk Solutions’ Lombardi.

Lombardi explained that an employer with an EMR of 1.00 is viewed as having an average loss experience for their workers’ compensation policy.

Thus, a contractor with a $1 million annual premium with an experience “mod” of 1.10 percent can expect to see premiums rise to $1.1 million, said the brokerage executive. By reducing its experience modification to .75, the company would see premiums go down accordingly, to $750,000, he said.

In addition to implementing a flex and stretch program, Bryan Schwartz, risk manager at American Infrastructure, said the company increased its workers’ compensation deductible four years ago to keep premium costs in check.

One additional measure the Worcester, Pa., company took: It hired a physician to serve as part-time medical director. The doctor is on call 24/7 to tackle issues related to worksite injuries.

“When an employee sustains an injury, the safety manager or foreman will call the doctor to help guide us through the medical treatment,” Schwartz said.

“He talks to the employee and asks how the worker would rate the level of pain being experienced or whether there’s swelling, for instance, and may recommend rest, ice or heat, or that the employee go to an occupational health clinic.”

If there are side effects to drugs recommended by the clinic, the medical director might make the appropriate inquiries and find the injured worker an alternative drug, he said.

Schwartz’ efforts have produced real results. With some 1,700 active construction workers across the mid-Atlantic states, American Infrastructure’s “recordable incident rate” as determined by OSHA rules, was “below a 1.5” for 2012, he said.

The average construction industry rate during 2011 — the latest date for which Bureau of Labor Statistics data are available — was 3.9.