Stand By for Turbulence: How a Deadly Virus and Unruly Passengers Have Shaken Aviation Safety

Nicole had enough.

Working as a flight attendant used to be fun. She loved engaging with smiling passengers. But ever since COVID-19, the mood on airplanes turned into a depressing blend of anxiety and stress.

Masks, goggles and hand sanitizer became a constant reminder of a deadly pandemic ravaging the world. Passengers refusing to comply with new safety precautions became a constant reminder of a nation deeply divided.

Nicole had the unenviable task of enforcing mask mandates. Some passengers pretended to nibble a granola bar as she walked by, taking advantage of a rule allowing them to remove masks while eating. Others were more brazen and simply removed their masks, essentially daring her to recommend an emergency landing.

“Flight attendants have become the mask police,” said Nicole, whose real name is being withheld because she’s not permitted to speak publicly. “My number one job is not to serve drinks. It’s to keep people safe. But it became exhausting.”

Crew members like Nicole are on the frontlines of America’s culture war, playing lion tamer between mask refusers and passengers demanding mask compliance.

The more dangerous work environment has led to a “disturbing increase” in verbal harassment, threatening behavior and violence, according to the Federal Aviation Administration.

When Nicole was offered furlough, she quickly accepted. The stress of passenger arguments and the ever-increasing harassment had worn thin. Plus, she was nervous about contracting COVID-19 and potentially infecting her roommate who cares for her elderly grandmother.

Nicole’s story is hardly unique. Crew members are increasingly concerned about their physical safety, mental health and the risk of contracting COVID-19.

In response, airlines have drastically transformed risk management procedures.

Read More: They Did What? Flight Attendants Tell Nightmare Tales from the Pandemic

To combat the virus, they are stepping up cabin air filtration, enforcing masks, reducing food-and-beverage service, and keeping people distanced at gates and terminals. To keep crews physically safe, airlines are changing messaging

to passengers, clearly communicating the severe repercussions for aggressive behavior or failing to comply with safety measures. Some even stopped serving alcohol to mellow the mood.

Airlines and their insurers hope the renewed safety efforts will entice more passengers to fly, keep risk exposure to a minimum, and give crews much-needed protection. If they are successful, the industry could be in a much better position as the pandemic wanes.

The Elephant in the Air

What are the risks of contracting COVID-19 on a plane? The data is hardly definitive. It’s difficult to determine exactly when and how someone contracted the virus.

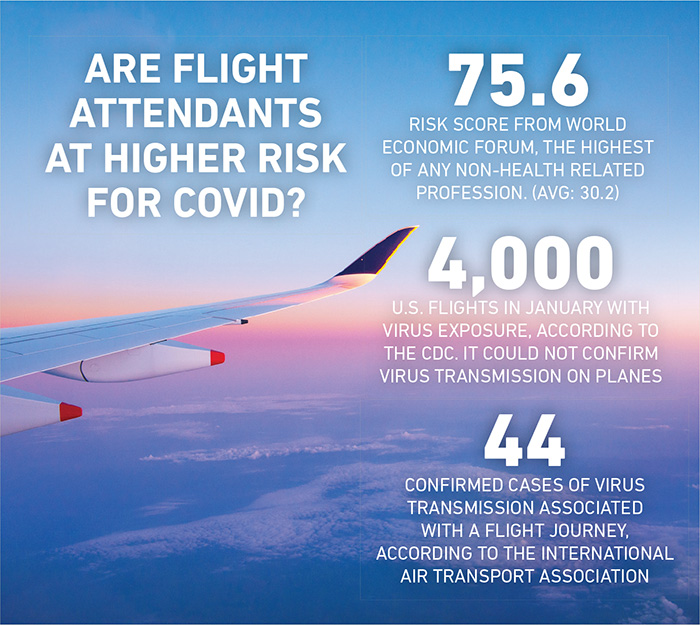

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found in September 2020 that 11,000 people were potentially exposed on flights but could not confirm a case of transmission on a plane due to incomplete contact tracing and the virus’ long incubation period.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) found in October that there had only been 44 confirmed cases of virus transmission associated with a flight journey. During that time, 1.2 billion people flew.

Still, David Powell, IATA’s medical advisor, said in a statement that those numbers “may be an understatement.”

Spending hours inside a thin metal tube without the ability to socially distance surely seems riskier than other workplaces. A World Economic Forum/ Visual Capitalist report found that flight attendants had the highest risk score of any non-health related occupation (75.6 out of an average of 30.2).

Sheri Wilbanks, global casualty risk consulting manager, AXA XL

The CDC says that difficulty social distancing on a flight may increase the risk of contracting COVID-19.

But in the same report, the CDC states that “most viruses and other germs do not spread easily on flights because of how air is circulated and filtered on airplanes.”

With such inexact data, crew members and passengers are forced to assess their own risk tolerance.

Paul Hartshorn Jr., a flight attendant at American Airlines and communications director of the Association of Professional Flight Attendants, said many crew members opted for voluntary leaves of absence. He said the union has helped them get some pay and benefits while on furlough.

“Flight attendants don’t just fly once a day,” he said. “Our days consist of three to four takeoffs, meaning we’re exposed to approximately 600-800 passengers per day. That certainly drives up the potential for exposure.”

Joel Heining, vice president at AssuredPartners, has been flying frequently during the pandemic

and working closely with aviation companies. He believes risk mitigation efforts are working.

“Airlines have HEPA filters that exchange the entire volume of the aircraft every three to four minutes. I’ve heard from aerospace engineers that the air is as sterile as any surgical room,” he said. “Nobody on an airplane wants to get sick. That makes it self-governing. By and large people who are flying are very careful, and it’s been a seamless, sterile environment from what I can tell.”

Shouting Matched and Physical Altercations

All airlines in the United States require masks. But once you get into the air, some passengers inevitably don’t comply. That can lead to heated debates between passengers.

Hartshorn said members of his union have seen shouting matches and even groups chanting back-and-forth. It was particularly tense during the Presidential election and the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol.

“The job has completely changed in the last year,” said Hartshorn. “There is aggression towards the crew members. There is aggression towards other passengers. It’s a tough environment.”

Crew members are trained to spot potential altercations before takeoff. They watch passengers’ moods, if they have been drinking, and if they are failing to comply with mask regulations in the terminal or gate. That lets them potentially handle dangerous situations on the ground — not in the air.

Hartshorn said flight attendant training is good, although flight attendants still felt unprepared for the current climate.

“We’re trained extensively on disruptive passengers as well as self-defense techniques. We are not trained for the mob mentality we saw in the past year with groups of passengers yelling and chanting, creating uncomfortable and dangerous situations onboard aircrafts,” said Hartshorn.

Airlines are putting disruptive passengers on temporary no-fly lists to curtail bad behavior.

Federal action could help, too. In January, the Biden administration mandated mask wearing on planes and in airports. At the time, airlines had already removed more than 2,500 passengers for refusing to fly with face coverings.

Meanwhile, the FAA announced it will forgo warnings and pursue stricter legal enforcement policy against unruly airline passengers who disrupted flights with threatening or violent behavior — with fines that can reach $35,000.

Sheri Wilbanks, head of casualty risk engineering at AXA XL, said having strict consequences that are clearly communicated could lead to better compliance.

“What is the consequence if you try to light a cigarette in the bathroom? You can be jailed or receive a fine,” said Wilbanks. “Passengers need to understand that non-compliance with safety measures or threatening staff has the same level of severity.”

Insurance Implications

Unlike other industries, “there are no COVID-19 exclusions in aviation liability insurance,” said Brad Meinhardt, area executive vice president and managing director of aviation at Arthur J. Gallagher, “but such exclusions have started to appear with respect to excess non-aviation liability insurance where provided. For example, excess employer’s liability and excess commercial auto liability.”

Not that underwriters aren’t trying. Meinhardt recalls an underwriter in Europe excluding any COVID-related claims. That led to swift action from Gallagher, which found the exclusion unacceptable.

“We made a decision to replace this security, because no other underwriter at that time had imposed such exclusion. It is painful because capacity is down, but we would never accept an exclusion on aircraft liability because the market has not broadly moved to that,” Meinhardt said.

Could an airline face a lawsuit or claim from a passenger who contracted COVID-19 on a flight?

“The feeling in the industry is that it’s nearly impossible to prove that somebody got COVID while flying in an airplane,” he said. “Did they have it before the flight? Were they a silent carrier? All these factors come into play.”

Workers’ compensation is another animal. If a flight attendant is hurt during a physical altercation with a passenger, they will obviously have a claim. If they contract COVID-19, getting workers’ comp coverage may depend on state laws, which vary greatly.

Another potential exposure is passengers suing airlines for false detainment or false arrest, but those exposures are typically covered, according to Meinhardt.

“Otherwise, I don’t think you’ll see a lot of claims from unruly passengers,” he said.

Some Safety Protocols Are Here to Stay

After vaccinations are widely distributed and travel resumes en masse, expect some safety precautions from the COVID-19 era to continue.

While mask mandates could eventually wane, airlines will likely keep up cleaning and sanitation efforts.

Meanwhile, filtration took a giant leap forward, and the industry has already been examining the use of ultraviolet light to kill bacteria. Around the world, temperature checks at airports, health declaration forms, and even contact tracing could continue, too.

“It’s a competitive advantage, especially if people are concerned about getting on airplanes and

need convincing that it’s safe,” said Meinhardt.

“The higher level duty for passenger safety from COVID will continue for a long time in the future.” &