2015 Most Dangerous Emerging Risks

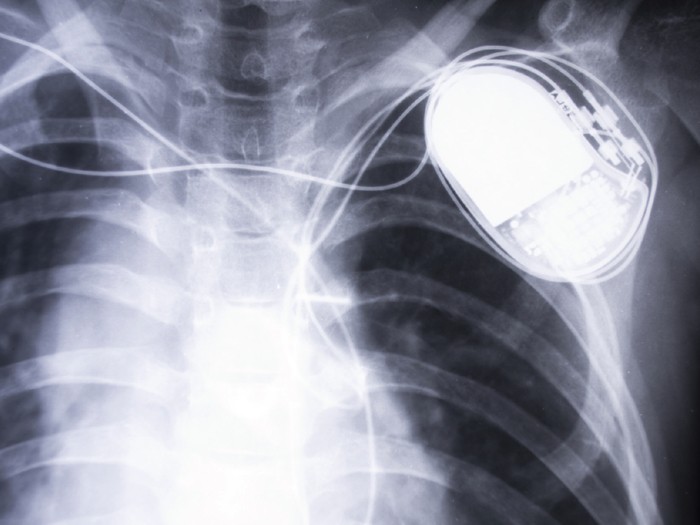

Implantable Devices: Medical Devices Open to Cyber Threats

SCENARIO: Pay off an anonymous hacker or face the possibility that patients with implantable defibrillators would die. That was the dilemma facing Janet Smith, CEO of Midtowne Community Hospital.

Too late she found out that the computer system of one of the surgical practices employed by the hospital was hacked. It was a simple enough operation. One unthinking click by the administrative staff on a link in an official-looking email, and the system was surreptitiously compromised.

The back-door access to the computer system provided the hackers with a treasure trove of unencrypted patient data including name, medical history, type of medical device implanted, and models and serial numbers of the devices.

While the hackers had a selection of devices to choose from — pacemakers, insulin pumps, cochlear hearing implants, blood glucose monitors and deep brain stimulators, among others — they targeted patients with implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs), which monitor and respond to heart activity by sending shocks to the system to restore normal heart rhythm.

The ICDs were designed to be wirelessly connected to external wands and ICD programmers. Data collected in the wands was downloaded to the IT system in the surgical practice so the physicians could review and manage each patient’s medical problems.

The RFID-enabled wands were supposed to be unidirectional, but the hackers were able to reverse-engineer the access after determining the radio frequency used and the engineering specifications of the ICDs and wands, which they found online — mostly in the technical and user manuals published by the manufacturers.

Each of the ICDs contained a small computer chip similar to those found in smart thermostats, televisions and refrigerators, all of which have been hacked recently to send out spam or just annoy users.

The hackers wrote and inserted programming code into the IT system of the surgical practice so that when information from the ICD devices was downloaded, code would be inserted that could induce fatal heart arrhythmia via the patients’ defibrillators.

It only required the hackers to trigger the code to activate it. And that’s what they threatened to do if the ransom was not paid.

While the extortion scheme was similar to the ‘Cryptolocker’ shakedown — which locks organizations out of their own files, forcing them to pay for access — this ICD threat offered a much more deadly outcome. And there was no positive outcome that Smith could see.

ANALYSIS: The hacking threat to implantable cardiac defibrillators has been known since at least 2008, when a team of university researchers proved it was able to reverse-engineer an ICD’s communications protocol to reprogram it to change the operation of the defibrillator, including its therapy settings.

Kevin Fu, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, who was on the team and is a leader in the field of device security research, likened implantable medical devices to unlocked cars during a presentation at Dartmouth University.

“There are people, if given the chance, who will cause harm and we shouldn’t just leave our doors unlocked,” he said.

While hacking is usually done for financial reasons, there have been instances where physical harm was intended, he said, mentioning an attack seven years ago on an epilepsy support group website, where hackers embedded flashing animation that induced seizures in those using the site.

“I think it would be naïve to ignore the fact that some of these people exist so we need to at least have a certain level of protection against this kind of maliciousness,” Fu said.

Michael Thoma, vice president, chief underwriting officer, global technology at Travelers, said he was “not aware of any actual claim or incident beyond what is available in the literature that it can be done,” he said.

“When you stop to think about the environment we are heading into — where hospitals are completely relying upon electronic medical records that are integrated to control medical devices in hospitals and obtain information back from the devices — the scenario exists that something like that could happen.

“You read all the time about attempts to attack all sorts of institutions, and hospitals are not immune to that. When you think about the ‘Cryptolocker’ scenario, not only could it bring a hospital to a complete standstill, but the reputational harm would be huge.

“It would make what happened in Dallas after Ebola at that hospital look minor,” he said.

‘A Hard Line to Cross’

“At the end of the day,” said Todd Lauer, vice president, medtech division, OneBeacon Technology Insurance, “you can sum it up in one sentence: Anything is possible for a determined hacker.”

Even so, he doubts most hackers would target the devices. “Most hackers are not looking to cause bodily injury,” he said. “They are looking to extort money from large corporations. That’s crossing a line. To cause bodily injury or death, that’s a hard line to cross.”

That leaves the possibility, however, that it could become a focus for terrorists looking to create panic and death, Lauer said.

Experts noted that as of now, hacking of implantable devices is only being done by researchers, universities and hackers who identify and expose security weaknesses.

“We are talking about something that certainly is possible, but it’s not an exposure that keeps me up at night as an underwriter.” — Mark Wood, president and CEO, LifeScienceRisk

Mark Wood, president and CEO of LifeScienceRisk, a series of RSG Underwriting Managers, acknowledged that it was “theoretically possible … . Am I aware that it’s happened? I have not yet seen a claim or a report that it’s happened.

“We are talking about something that certainly is possible, but it’s not an exposure that keeps me up at night as an underwriter.”

It’s more likely that instead of the sophisticated scenario portrayed above, hackers would simply use RFID to jam the devices with a denial-of-service attack, said Jerry Irvine, CIO of Prescient Solutions, who is also on the National Cybersecurity Task Force.

“They could basically overburden it so much that it can no longer react, so people will die or equipment will malfunction or give an overdose of medication,” he said.

“That’s the easiest thing you can do. You can do that from 100 to 300 yards away with targeted antennas or high-powered antennas. These are things that are not difficult to do.”

In addition, researchers have noted that many hospital IT systems lack cutting-edge cyber security.

“Unfortunately, computer security in many hospitals and similar providers reminds me of the very early days of computer security when security was the domain of system administrators and network security types,” said Gary McGraw, chief technology officer at software security consultancy Cigital Inc., in an article on SearchSecurity.com, a site of “Information Security” magazine.

McGraw likened hospital network security administrators to “plumbers who make sure that infrastructure is properly designed and operates smoothly. Generally speaking, though they are certainly important, plumbers are not very strategic thinkers and neither are system administrators.”

Federal Government Action

In 2012, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that in controlled settings that did not involve actual patients, security researchers “recently manipulated two medical devices with wireless capabilities — a defibrillator and an insulin pump, a type of infusion pump — demonstrating their vulnerabilities to information security threats.”

It concluded that implantable medical devices (IMDs) are “susceptible to unintentional and intentional threats … . Information security risks resulting from certain threats and vulnerabilities could affect the safety and effectiveness of medical devices. These risks include unauthorized changes of device settings resulting from a lack of appropriate access controls.”

It concluded that implantable medical devices (IMDs) are “susceptible to unintentional and intentional threats … . Information security risks resulting from certain threats and vulnerabilities could affect the safety and effectiveness of medical devices. These risks include unauthorized changes of device settings resulting from a lack of appropriate access controls.”

The report also noted that the “growing use of wireless capabilities and software has raised questions about how well [IMDs] are protected against information security risks, as these risks might affect devices’ safety and effectiveness.”

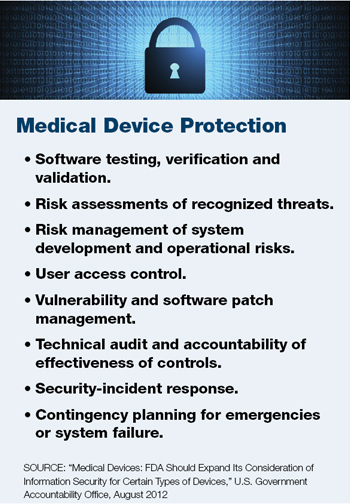

That prompted a review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which two years later, in 2014, offered guidance to strengthen the safety of medical devices to better manage cyber security risks.

“There is no such thing as a threat-proof medical device,” Dr. Suzanne Schwartz, director of emergency preparedness/operations and medical countermeasures at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said at the time. “It is important for medical device manufacturers to remain vigilant about cyber security and to appropriately protect patients from those risks.”

Top concerns included malware infections on network-connected medical devices or computers, smartphones and tablets used to access patient data; and failure to provide timely security software updates or patches to devices or networks.

The guidance recommended to manufacturers that they consider cyber security risks as part of the design and implementation of medical devices, and submit documentation to the FDA about the risks they identified and the controls put in place to mitigate those risks.

It also recommended that manufacturers submit plans for providing patches and updates to operating systems and medical software.

Still, said Jay Radcliffe during a presentation at the 2013 Black Hat Conference, cyber security concerns have not been cited by the FDA as a reason for rejecting any implantable medical devices.

And, said OneBeacon’s Lauer, patching implanted devices is difficult, as it often requires surgery.

Manufacturers rarely seek to enhance devices via patching because it requires “an onerous regulatory process” with the FDA, said Tam Woodron, a software executive at GE Healthcare, in an article in “MIT Technology Review.”

The article also noted that reporting of incidents is not required by the FDA unless a patient is harmed.

A study by researchers at MIT and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst found that there are millions of people with wireless implantable medical devices, and about 300,000 such IMDs are implanted every year. The life of such a device can last up to 10 years.

Liability Concerns

Wood of LifeScienceRisk said that if a device malfunctions and results in bodily injury, regardless of the reason, there would likely be an allegation of product liability.

“There wouldn’t be any limitation, at least in the coverage we write, about whether a software error created the problem,” he said. “The malfunction in and of itself would trigger coverage if it caused bodily injury.”

If a carrier’s coverage did exclude software issues, the insured’s E&O policy would probably be triggered, he said.

As for who would be involved in such a claim, the list could be a long one, including the hospital, physician, caregivers, device manufacturer, Internet provider, cloud provider, and anyone who provided consulting services to anyone involved in the process, plus all of their insurance companies.

Lauer noted that when claims involve device manufacturers, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling prevents plaintiffs from relying on state negligence or liability rulings; the High Court determined that such laws cannot pre-empt federal laws and the FDA’s safety determinations.

“The exposure is going to be different for any set of facts,” Wood said. “The more complicated the loss scenario, the more potential for coverage issues in trying to figure out whether and how a claim should be covered.”

If extortion or crime is involved, it’s unclear if that would be an insured loss, he said.

![]()

Complete coverage of 2015’s Most Dangerous Emerging Risks:

Corporate Privacy: Nowhere to Hide. Rapid advances in technology are ushering in an era of hyper-transparency.

Corporate Privacy: Nowhere to Hide. Rapid advances in technology are ushering in an era of hyper-transparency.

Implantable Devices: Medical Devices Open to Cyber Threats. The threat of hacking implantable defibrillators and other devices is growing.

Implantable Devices: Medical Devices Open to Cyber Threats. The threat of hacking implantable defibrillators and other devices is growing.

Athletic Head Injuries: An Increasing Liability. Liability for brain injury and disease isn’t limited to professional sports organizations.

Athletic Head Injuries: An Increasing Liability. Liability for brain injury and disease isn’t limited to professional sports organizations.

Vaping: Smoking Gun. As e-cigarette usage rises, danger lies in the lack of regulations and unknown long-term health effects.

Vaping: Smoking Gun. As e-cigarette usage rises, danger lies in the lack of regulations and unknown long-term health effects.

Aquifer: Nothing in the Bank. Once we deplete our aquifers, there is nothing helping us get through extended droughts.

Most Dangerous Emerging Risks: A Look Back. Each year since 2011, we identified and reported on the Most Dangerous Emerging Risks. Here’s how we did on some of them.