Health Care Risk

Health Technology’s Deadly Risks

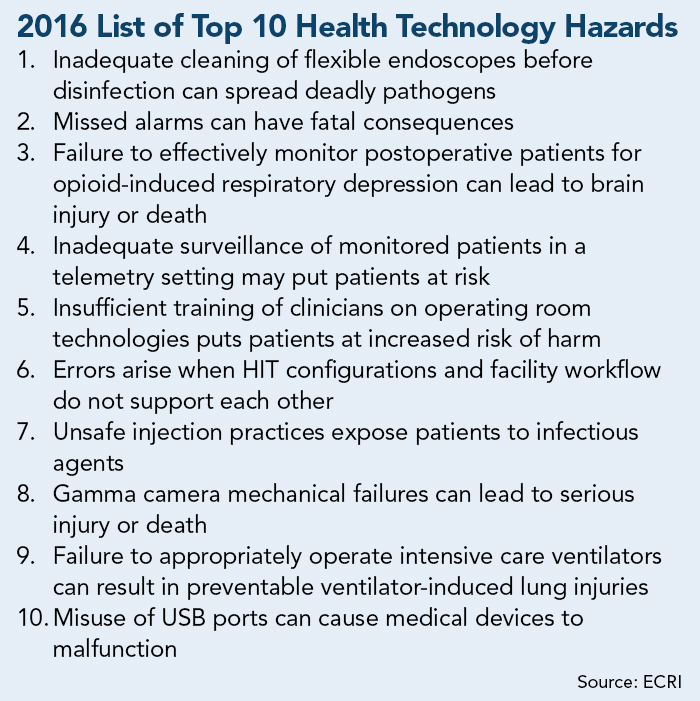

In the hazard-rich world of health care, risk management professionals are working to direct their resources where they can have the most impact on patient and employee safety. To support their efforts, the ECRI Institute created its annual Top 10 Technology Hazards list.

The ECRI Institute is a nonprofit dedicated to patient care research based in Plymouth Meeting, Pa. The publication of the ECRI list is now in its ninth year.

A team of 70 ECRI engineers, scientists, clinicians and patient safety analysts votes on the final list. Hazards are nominated for the list based on adverse event reports, equipment testing, accident investigations, consulting work and input from clinicians and manufacturers.

“We want this to be a practical tool, not just setting people’s hair on fire worrying about things,” said Rob Schluth, senior project officer at ECRI Institute and the lead project manager for the Top 10 list project.

Topping this year’s list — an issue that has been frequently in the news over the past year — is bacteria spread through contaminated endoscopic devices. After contact with reusable devices called duodenoscopes between late 2014 and early 2015, two patients died and five more were infected by a drug-resistant “superbug” bacteria at UCLA Ronald Reagan Medical Center.

At a media briefing at ECRI’s Pennsylvania headquarters, a hands-on demonstration of the way such scopes work made it plain how easily such bacteria could survive the cleaning and disinfecting process.

The problem, explained Chris Lavanchy, engineering director of ECRI’s Health Devices Group, is not necessarily a failure in the disinfection/sterilization phase, as most would assume. The manual cleaning prior to sterilization can be inadequate.

This is partly due to the level of difficulty in cleaning small holes and crevices thoroughly, and also because “it’s a blind process — you can’t see inside the scope,” Lavanchy explained.

Exacerbating the problem, the scopes are expensive, so facilities may have only a few to go around. That leaves technicians under pressure to clean and sterilize the scopes quickly so they can be used for the next procedure.

“The [manual] for cleaning these things is 100 pages long,” he said. And yet the manual cleaning phase is often done in as little as 15 minutes.

Deadly Injections

Surprisingly, ECRI’s list included one technology that is decidedly low-tech, although the risks it poses are high. Unsafe injection practices remain a persistent problem in health care settings nationwide.

Some practitioners, while diligent about disposing used needles, will simply snap new needles on syringes that have been used, if the syringe will be used again for the same substance.

The problem with that, explained ECRI’s Senior Infection Prevention Analyst Sharon Bradley, is that there may be a microscopic amount of blood that has been transferred to the syringe. That blood will then be transferred to the new clean needle that gets attached, and then to the next vial of medication that needle is injected into.

Bradley referenced a massive outbreak of Hepatitis C in Fremont, Nebraska, in 2001, when 99 chemotherapy patients were infected when nurses repeatedly failed to change syringes while cleaning cancer patients’ ports using a community saline bag.

Time has not done much to temper the risk. This past October, 67 people were exposed to potentially contaminated blood when a visiting nurse reused a syringe to administer shots during an employer-sponsored flu clinic in West Windsor, N.J.

“Thousands of people are getting hepatitis that way,” said Bradley.

Some practitioners may be taking shortcuts with syringes or IV bags because of a lack of education about how contaminated blood may be present even when invisible to the naked eye. In other cases, those administering injections may have been instructed to reuse supplies in a misguided attempt to cut costs.

Fixing the problem, said Bradley, will be a matter of helping the industry understand that “the risk of negative outcomes outweigh the cost or inconvenience of doing it right.”

While ECRI does not have exact figure on the frequency of contamination incidents, “it happens more often than you think,” said Bradley. It’s worth noting that approximately 90 percent of contamination incidents originate in outpatient clinics.

Training Shortfalls

ECRI estimates that approximately 70 percent of accidents involving a medical device can be attributed to user error, which isn’t all that surprising. One key to the problem is a disconnect between health care facilities and health equipment manufacturers, particularly in the area of operating room technologies.

Competitive practices among manufacturers often create fundamental differences in the operation of machines that serve the same purpose. Identical functions typically are labeled with different words or phrases, or control switches or buttons may be vastly different.

Similar issues face clinical practitioners that operate intensive care ventilators, potentially leading to lung injury or death for vulnerable patients.

Marc Schlessinger, senior associate at ECRI, likened it to the way most mobile phone users felt lost when the switch from flip phones to smartphones first occurred. The difference is that pressing the wrong button on your phone isn’t likely to put a patient’s life at risk.

Comprehensive training would seem one obvious solution, but that’s not always happening, Schlessinger explained. While manufacturers typically offer training, facilities don’t necessarily require clinicians to complete training, or they train one “super user” and rely on trickle-down training practices that aren’t always formalized or followed up on.

Another risk on ECRI’s list this year is the persistent problem of missed clinical alarms — a hazard that has topped the list every year it’s been published. Other hazards highlighted include the accidental misuse of USB ports on medical devices as well as crushing risks from defects or damage to heavy gamma cameras used in certain types of scans.