Emerging Risk: Drones

Government Drones Are Everywhere and Risk Managers Better Catch Up

In the wee hours of a frigid February night in the village of Ludborough, Lincolnshire, England, a motorist flipped his car on an isolated road. Dazed, he wandered away from the scene and was spotted by a passerby who alerted authorities.

Local police deployed a drone equipped with thermal imaging to aid in the search. The drone found him within minutes, unconscious and hypothermic, at the bottom of a ditch he’d stumbled into. Officials acknowledged he might have died were it not for the quick action of the search team and their drone.

In the U.S., similar scenarios are unfolding across the country. In June 2017, two hikers and their dog got lost in Colorado’s Pike National Forest. Douglas County Search and Rescue dispatched a drone above the vast expanse of treetops and found the trio in less than two hours.

A few months later, local police using a drone took less than 30 minutes to locate an 81-year-old woman who’d become lost in a cornfield in Asheboro, North Carolina.

“I imagine that if Superstorm Sandy were to happen today, they’d be using [drones] a lot more to help find people that were still out there,” said Edward Cooney, VP, account executive and joint insurance fund (JIF) underwriting manager, Conner Strong & Buckelew.

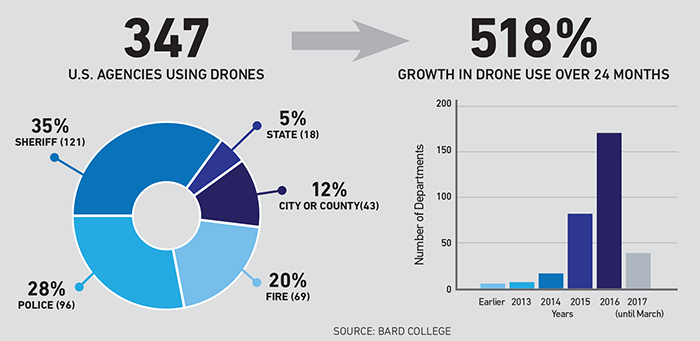

But search-and-rescue is hardly the only application for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in the public sector. According to a recent study published by Bard College’s Center for the Study of the Drone, the adoption of UAVs by public safety agencies has been accelerating rapidly ever since the introduction of inexpensive consumer drones in 2014.

As of March 2017, nearly 350 police and fire departments in 43 states are using UAVs, for everything from crime scene photography to locating suspects and stolen property to conducting safety and risk assessments during active fires and locating people trapped inside burning buildings.

Drone applications outside of law enforcement and fire safety are growing as well. Cooney, whose organization runs two large municipal entity pools, said its member towns are either using UAVs or considering their use for a broad range of applications, including:

- mass distribution of medications in the event of emergencies;

- identifying and tracking oil spills and other hazardous material releases;

- geotagging sewer pipes or boilers throughout townships;

- forestry applications, such as monitoring wildlife and the depletion or overgrowth of forests;

- heat-mapping facilities, such as utility authorities and waste utilities to watch for hotspots that could potentially cause fires;

- recording noise levels to investigate civilian noise complaints;

- remote water testing in areas that are difficult to access; and

- bridge monitoring and assessment.

Fear of Overreach

The versatility of drones, their speed, efficiency and relatively low cost is prompting calls for expanded use. Following the mass shooting in Las Vegas, a terrorism expert spoke out about the need for drones to be deployed to assist police in gathering real-time intelligence during such incidents. The president of the Los Angeles Police Commission concurred, suggesting the shooter’s location might have been pinpointed faster had a drone been deployed.

A combination of federal and local laws, however, place certain limits on expansion. Public drone operators, like their private counterparts, are subject to Part 107 of the FAA’s Small UAVs Rule. Part 107 specifies where and when drones can be operated and the maximum speed and altitude of operation, among other things. It also specifically prohibits the use of drones at night or directly above people without a Special Governmental Interest waiver from the FAA.

“I imagine that if Superstorm Sandy were to happen today, they’d be using [drones] a lot more to help find people that were still out there.” — Edward Cooney, VP, account executive and joint insurance fund (JIF) underwriting manager, Conner Strong & Buckelew

Local laws governing public drone use often reflect public and political pressures in a region. Seattle’s police drone program was scrapped in 2013 after public outcry that the program would create a “surveillance state.” For similar reasons, the LAPD had no drone program prior to 2018, even though the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department currently operates such a program.

Most agree that, used judiciously, drones can be a valuable tool to help protect law enforcement, firefighters and the public. “Mission creep” is the biggest concern of opponents, who argue that while the technology might be employed with good intentions initially, it’s inevitable that lines will be crossed, putting civil liberties in jeopardy. It’s a very small leap, for example, from drones equipped with cameras to drones equipped with sophisticated facial recognition technology.

While the privacy debate will likely continue to stir controversy across states and municipalities, it may pale in comparison to the next frontier: the weaponization of public drones. No U.S. public safety department currently utilizes weaponized drones. A Connecticut bill that would have criminalized weaponized drones, but left an exception for law enforcement, never got past committee.

Just five states — Nevada, North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont and Wisconsin — directly ban the use of weaponized drones.

In North Dakota, a bill intended to limit police use of drones took a curious turn due to an amendment proposed by a police lobbying group. The adopted amendment enables police drones to use “less than lethal” weapons, such as tasers, bean bags, pepper spray, sound cannons and rubber bullets. No departments in North Dakota are known to be currently using UAVs equipped with nonlethal weapons.

Coverage for Drone Risks

Public sector risk managers can best serve their entities by ensuring all pieces are in place for an effective drone program that serves the interests of its employees and citizens.

Agencies getting it right are the ones that approach it with the same amount of care as if they were buying a helicopter, said James Van Meter, drone expert and aviation practice leader with Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty. A drone employed in the interest of public safety “can provide great benefits, but it requires specialized training and licensing.

“There’s a lot of expertise involved in actually using this equipment to obtain the data or the images that you’re trying to obtain,” he said. “It requires special training, a special skillset and experience with it.”

Agencies should establish standard procedures for how to set the equipment up, how to check it, how to verify it’s safe before launch, how to operate it properly and safely over the areas it will be flown.

“Having the aviator mindset, as we like to call it, really makes all the difference,” said Van Meter.

Appropriate coverage is vital to protect the agency and the municipality. Van Meter said drone operators in the public sector typically buy hull and liability coverage and, in some cases, privacy coverage as well.

“Some risk managers view [privacy risk] differently, because privacy in the law enforcement context is very clearly covered and defined by the Fourth Amendment,” Van Meter explained.

“It’s a lot different for me, as a private citizen, if I’m capturing images that potentially could be violating someone’s privacy versus a law enforcement agency flying their helicopter over someone’s backyard to see what’s growing back there,” he said.

In fact, two cases in the late 1980s specifically addressed whether police were in violation of the Fourth Amendment when—without a warrant— they used drones to identify marijuana plants being grown on private property. The courts found in favor of the police in both cases. In one of the cases, the court concluded a warrant wasn’t necessary when capturing images easily visible to the naked eye from 1,000 ft.

However, current imaging systems are more advanced than they were 30 years ago, so the naked-eye holding might not stand today. In addition, U.S. courts have not clearly defined where private property ends and public airspace begins, so a drone flying at 500 ft. might net a different verdict.

Cyber Concerns

As with any other connected device, cyber security is a concern. The two key cyber concerns related to drones fall into different buckets with regard to coverage.

A breach of the data obtained by a drone would require the same type of coverage as any other breach, said Van Meter. If a drone captures sensitive data on a suspect, a crime scene or people who’ve been injured or killed, a bad actor could conceivably hack the agency’s database and post those images on the internet.

That scenario would fall outside of an aviation policy but should be covered by the agency’s cyber policy. A cyberattack with physical damage to the drone is a different matter, said Van Meter.

“An attack on the drone itself, what’s called spoofing, is where someone hostilely is trying to either jam the signal so that the drone crashes, or potentially take over control of the drone,” he said. “Both of those scenarios would be covered under war coverage on our policy, because that is [considered] a hostile takeover or hijacking of the aircraft.”

War coverage also applies to non-cyberattacks, such as when a suspect shoots at a drone and causes damage.

The increase in public sector uptake of drones has been explosive. According to the Bard College study, usage by police, sheriffs, fire departments and other municipal agencies grew by 518 percent within the two years prior to the study’s release.

Risk vs. Reward

Most of the risks posed by drones are not new, noted Cooney. Bodily injury and property damage are risks public entities already manage. Privacy invasion claims also are a well-understood risk, particularly for public entities that employ video cameras or body cams.

Still, transparency is a solid mitigation strategy for agencies or municipalities operating UAVs, said Mark Aitken, senior policy advisor with Akin Gump and a former director of government relations at the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International.

“Someone sees a drone, and they’re in their backyard sunbathing — they think their picture’s being taken,” said Aitken.

Education and outreach efforts are needed to help citizens understand what purpose the UAVs are actually serving, he said.

“If they were to hold [some kind of] workshop and say, ‘Hey, you might see these things around — here’s what we’re using them for,’ I think that that can go a long way. It takes the guessing game out of the equation where people automatically assume [that it’s] not being used in the right manner.”

The FAA’s website hosts a wealth of information and guidelines. Each entity must then “consider what are their own tolerances and thresholds for perhaps going above and beyond what the FAA has put in place,” Aitken said.

Well-designed policies and procedures — developed in-house or with the help of a safety management organization — help organizations ensure a level of professionalism with their drone operations and pilots.

“While there are certain risks inherent in the use of drones,” said Cooney, “it’s important to understand all of the risks that it could be offsetting. We’re trying to balance that risk and reward. That’s why we went into offering coverage for all of our members, because we think that there’s a lot of benefit from a safety perspective that they can offer.”

Added Van Meter: “It just makes so much sense to equip law enforcement officers with this technology. It can help … save innocent people, but also protect law enforcement officers and firefighters.

“The more knowledge they have of what they’re about to walk into, the more knowledge they have about the situation that they’re encountering, the better decisions they can make and the better they can act to protect themselves and the general public.” &