Pharmacy Cost Control

Formularies Rise in Popularity

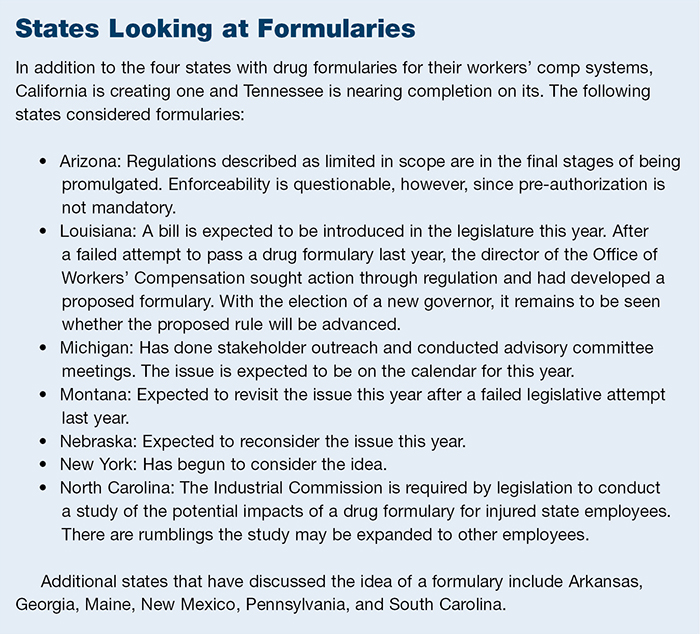

Texas, Oklahoma, Washington, and Ohio have them. California and Tennessee are creating them. And a slew of other states are looking to drug formularies as a way to address pharmaceutical issues in the workers’ comp system.

Since adopting its formulary more than four years ago, Texas has seen significant reductions in the percentage of injured workers receiving inappropriate medications, along with dramatic cost reductions for new claims. Likewise, Ohio regulators report decreases of 74 percent for skeletal muscle relaxants, 25 percent for narcotics, and a reduction in total drug spend of 16 percent since its formulary took effect. Despite the impressive results, experts say formularies are not necessarily a panacea, and care is needed to ensure they are effective and avoid unintended consequences.

“Some pretty significant states in terms of size and geography are looking at this and saying, ‘this may be something we want to do,’ as another tool in helping to control utilization and costs in workers’ comp,” said Kevin Tribout, executive director of government affairs for pharmacy benefit manager Helios. “It creates a speed bump. It creates some regulatory teeth for a physician.”

Different Types

“A formulary is a list of medications that are approved and deemed appropriate for treatment,” explained Joseph Paduda, principal of Health Strategy Associates and president of CompPharma, an association of PBMs. “There’s some methodology used to develop that list and put drugs on that list or exclude drugs from it. … That’s the most basic process.”

Many jurisdictions have open drug formularies for workers’ comp, for example, that allow any medication to be approved as long as the physician writes the prescription. Closed formularies, on the other hand, are lists of specific medications that require prior approval for reimbursement.

“In a closed formulary such as the one used today in Texas and Oklahoma, it’s a binary, yes/no decision,” Paduda said. “Regardless of the diagnosis, disease state, or patient need, a physician can order [the drug], the pharmacy can dispense it, but the payer can refuse to pay for it saying ‘it’s not appropriate for that particular workers’ comp injury or illness.’ But a payer cannot stop the pharmacy from dispensing it.”

Formularies are — or should be, according to the experts — developed in an open, transparent process using robust, scientifically valid evidence. Developed and implemented effectively, formularies can be a game changer for the workers’ comp system.

“If you are policymaker thinking about it, ask yourself: Is your goal to save money or improve outcomes? The answer is going to determine how you approach the formulary.” — Phil Walls, chief clinical officer, myMatrixx

“In the vast majority of states, whatever medication is prescribed is filled,” said Dr. Robert L. Goldberg, chief medical officer for PBM Healthesystems. “There’s absolutely no control over the selection of the medication, let alone brand name vs. generic, let alone what is medically necessary, let alone the cost.”

Formularies, Goldberg said, can define what is appropriate for a particular condition or diagnosis, or phase of treatment. “So you create boundaries and narrow the choices based on what is reasonable and what is necessary. As you start to narrow that down, by definition you have a great opportunity to get the right drug to the patient and also control cost — partly from avoiding overutilization or the dispensing of medications that are much more expensive but don’t provide any significant benefits.”

The overprescribing of some medications, notably opioids, is expected to decrease when a drug formulary is in effect. Evidence out of the states with formularies show that to be true.

There is also research indicating that treating physicians change their prescribing patterns because of drug formularies and are more inclined to prescribe medications they know will be approved.

“If I were a physician, I would know what medications are on the list that require prior authorization,” Tribout said. “So, if I write a script, I know more than likely it will come back requiring prior authorization and I would have to justify why; or I can simply write a prescription that doesn’t require prior authorization, my patient can get the prescription filled, and there are not three or four phone calls to be made. So injured workers are still getting care, being treated and returning to work, and physicians are changing their prescribing patterns — not reducing care, just changing their prescribing patterns to potentially provide more efficacious treatment.”

Formularies also empower physicians by giving them a reason to deny unnecessary medications to a patient without fear of losing the patient’s trust.

Both the Official Disability Guidelines created by the Work Loss Data Institute and the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine have formularies that can serve as a basis for the design of a formulary. A proposed formulary in Tennessee, for example, is a hybrid of the ODG and the state Department of Health Chronic Pain Guidelines.

The widely used ODG Appendix A includes a list of approved and unapproved medications. Those on the “Y” list are deemed acceptable and reimbursable while “N” medications require pre-authorization.

Texas, which uses the ODG formulary, has a more inclusive list of drugs not requiring pre-authorization, and all other medications are included. Formularies in Washington and Ohio consist of preferred medication lists, and providers prescribe off that list.

ODG recently moved some opioids on its formulary — morphine extended release, Embeda and Fentanyl patches — from the “Y” list to the “N” list. Texas is slated to make that change next month.

“This decision by the ODG means that two of the most commonly prescribed long-acting opioids for chronic pain will now require prior authorization. That means that tramadol ER will be the only long-acting opioid that can be prescribed without requiring prior approval or, in other words, has ‘Y’ status,” said Paul Peak, director of clinical pharmacy at third-party administrator Sedgwick. “It’s a big change. … It seems that the Work Loss Data Institute is updating their formulary to show what the clinical data supports, which is that long-acting opioids should not be seen as the first line options for chronic, non-malignant pain. We’re making adjustments on our end so injured workers in Texas are aware and what that means for them.”

The ACOEM-based formulary launched in late 2015. Proponents say is more robust than other formularies in that it addresses a person’s disease state.

“It’s an injury-based formulary and so far, it’s based on each of the chapters of the ACOEM Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines,” said Goldberg, who was the primary developer of the ACOEM formulary. “For example, we took low back pain. That chapter has multiple conditions. For each condition we looked at each class of medication and broke it down into each medication within a class. So you have a stair stepping that narrows the selection.”

Goldberg said the formulary also addresses acute vs. chronic phases of treatment. Each condition is searchable by both the ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes and includes cost information for each medication.

“The whole idea was to primarily guide physicians but also payers, other medical and health care professionals, and ultimately regulators in terms of what are the best choices and what are the evidence-based recommendations for a treatment and a condition and do it by class and by individual medication,” Goldberg said. “So it’s a very deep and broad formulary with great specificity and has a very strong evidence base.”

What makes one formulary better than another depends on a variety of factors, especially the policies within a particular state. However, the evidence used as a basis is key since this is the reason for the formulary.

“If you are policymaker thinking about it, ask yourself: Is your goal to save money or improve outcomes? The answer is going to determine how you approach the formulary,” said Phil Walls, chief clinical officer for PBM myMatrixx. “When I look at ODG there is a significant focus on cost containment. There is nothing wrong with that. We should save money. But if your focus is not just on getting rid of expensive drugs, it changes the whole dynamic — to a clinical rather than financial approach. Oftentimes, they go hand in hand but not always.”

All Eyes on California

Many eyes are on California as it develops a drug formulary. Legislation requires a plan to be in place by the summer of 2017.

“It’s a really crucial state in the workers’ comp world,” Peak said. “I believe California’s decision to move forward with a formulary because of its large impact in workers’ comp will be a big impetus for other states to consider.”

The formulary created in California must be in sync with state rules and policies in order to be effective. Despite the success of Texas’ formulary, that is not necessarily the best model for other states.

“The ODG formulary works in Texas because of Texas’ statutes,” Walls said. “The regulations they have around utilization review and retrospective denial makes the formulary work … but ODG is not a one size fits all.”

In fact, adopting the Texas-style formulary verbatim could end up costing extra in other states. As Walls explained, Texas’ formulary allows for a variety of medications that address conditions not typically associated with occupational injuries and illnesses. Once the medication has been prescribed and paid for, payers can retrospectively review the claim and deny payment.

“Most states don’t allow that. So when someone wants to adopt ODG, they really want to adopt a portion of ODG,” Walls said. “If you look at the top drug categories in comp — opioids, NSAIDs, anti-convulsants, etc., — yes, follow ODG. But don’t add anti-hypertension medications or you’ll pay for group health claims. I call it ‘ODG with common sense.’”

UR needs to go hand-in-hand with a formulary for it to be successful. As one expert said, a formulary without UR lacks enforcement capability; whereas UR without a formulary lacks something to enforce.

“A formulary is analogous to a speed limit,” Paduda said. “You can put speed limit signs up and you can hope people will obey, but that’s not a strategy. What you really need, along with a formulary, is a UR program that is tied to ensuring that medically necessary, safe drugs are approved quickly, drugs deemed not medically necessary are not approved, and there is a quick and appropriate and medically sound decision-making process when a drug is initially not approved and the treating physician appeals it.”

States considering formularies need to carefully evaluate their own policies to see what they want to include and how it should be implemented. Otherwise, they risk unintended consequences.

“Kudos to Texas for jumping in quickly; however, it has had a dramatic impact on the volume of opioids paid for in the workers’ comp system,” Paduda said. “But what happened to those patients on opioids? That’s the great unknown. … You can’t just pass a formulary and say ‘we’re in good shape here.’”

Making It Work

Creating a formulary is just the first step. Also imperative is getting medical professionals to adhere to it.

“If physicians don’t want to comply, they say ‘I don’t have to do it; they are just guidelines,” Walls said. “In workers’ comp, more than in group health, it needs to go beyond the list of drugs; it needs to support what guidelines say.”

Educating physicians on the formulary is imperative. “That is huge,” Walls said. “There is not nearly enough of that.”

A formulary that is well-founded on scientific evidence and can be accepted and understood by prescribing physicians will be more effective, experts say. “The whole idea of any set of treatment guidelines or formulary is it should cover 80 percent to 90 percent of cases so everybody knows what’s in play,” Goldberg said.