Aviation

Drones, on Demand

When the Federal Aviation Administration eased licensing requirements on piloting drones in late August, conditions ripened for explosive growth in their use. Yet the vast majority of drones are not insured, according to experts.

More than 600,000 drones will be sold this year for commercial use in the skies over the United States, according to FAA estimates. That’s three times more than manned aircraft such as airplanes and helicopters. An additional 1.9 million drones will be sold to hobbyists for recreational use, the FAA forecast earlier this year.

Look ahead to 2020 and the FAA expects there will be more than 4.7 million drones flying worldwide. Each and every one has the potential to crash into buildings, wires or worse, people. The downstream effect of these accidents could be more worrisome than the crash itself.

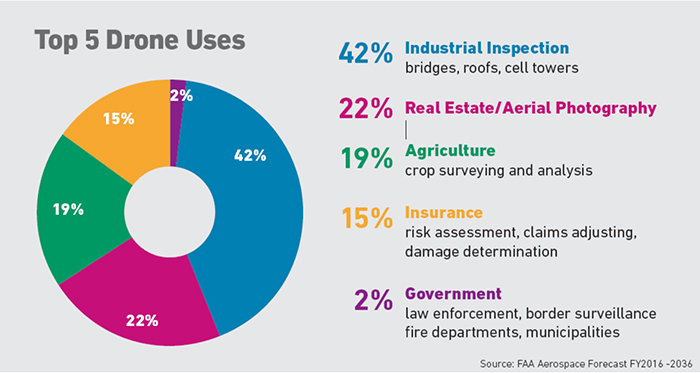

Increasingly, drones are a standard business tool used to survey crops and construction sites, photograph properties for real estate listings and insurance assessments, and even to deliver goods. Expect them to become much more commonplace as companies discover new and creative uses, and drone manufacturers find ways to make them smaller, cheaper, safer and easier to use.

Yet, 80 percent of all drones in use today may be uninsured, according to one estimate. Many are piloted by neophytes who sat on the sidelines until the FAA’s less restrictive guidelines opened the door for them to soar the skies this year.

“For the first time in aviation history, you’ve got tens of thousands of people bringing flying lawn mowers up into the air without any formal background in aviation training or any understanding of the international air space system,” said Alan Perlman, the founder of UAV Coach, a website offering industry information and training certification to drone pilots.

Swiss Re brought together drone experts, hackers, business leaders and insurance experts to discuss the risks and insurance underwriting of drones.

More drones taking to the skies add new risks and vastly change the insurance business, according to a report by Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty (AGCS): “Rise of the Drones: Managing the Unique Risks Associated with Unmanned Aircraft Systems.” The U.S. drone insurance market may be worth more than $500 million by the end of 2020, according to the report. Globally, it could approach $1 billion.

Global Aerospace Inc., a leading provider of aircraft insurance and risk management solutions, was one of the first to offer drone insurance under an aviation policy just four years ago.

“The sheer volume of requests for insurance is fast becoming overwhelming, and I think it will continue to grow at an exponential pace,” said Christopher Proudlove, senior vice president, general aviation team leader of the Northeast regional office at Global Aerospace.

“Covering the hazards and coming up with the appropriate products is probably the easiest part; dealing with the volume is going to be a challenge.”

Insurers are working to offer affordable products to the growing crowds of drone pilots. Niche brokerages aimed at commercial drone pilots are springing up, as are tech startups offering on-demand insurance apps, Uber-like drone pilot searches and safety features for night or long-distance flying.

On-Demand Drone Insurance

One company, Verifly, developed a mobile application offering on-demand drone insurance at hourly rates.

Verifly was launched in August in a partnership with Global Aerospace. It offers $1 million in liability insurance for as low as $10 an hour on any drone weighing less than 15 pounds and flying up to a one-quarter mile away from the pilot. Users order the insurance on their phones and receive instant approval.

Verifly uses geospatial mapping to assess the risks based on location and current weather conditions to provide a real-time quote. Users can purchase third-party liability insurance instantly. Coverage includes injury to people and property damage, unintentional invasion of privacy and unintentional flyaways.

“We are assessing ways to make the process of buying drone insurance easier because we recognize the fact that the vast majority of operators are millennials who rely on their smart phones,” Proudlove said.

“We definitely have some projects in the works that will help facilitate buying insurance. This is a user group that won’t be walking down to the local insurance office to fill out an application with a pen.”

FairFleet, developed in partnership with Allianz X (which helps develop new business ideas in the insurance space), is another new product that could be described as Uber for the drone business. Currently available in Europe — and planned for the U.S. next year — it connects “drone for service” pilots with nearby businesses in need of one-off jobs.

The FAA Requirements

Under the updated FAA rules, commercial drone pilots must pass a written test to receive certification. In the past they were required to obtain a manned aircraft pilot’s license first and submit detailed logs for each flight.

Now, owners register when they fly an unmanned drone outdoors weighing more than 0.55 pounds but less than 55 pounds. Under FAA regulations, devices can’t be flown higher than 400 feet and should not fly over populated areas, near airports or after dark. The operator must be able to see the device at all times.

The FAA is working with companies such as CNN (on using drones for newsgathering in populated areas) and BNSF Railroad (on using drones in rural/isolated areas out of sight of the pilot) to test safety technology under a program called Pathfinder.

While operators must have a drone pilot certification, there’s currently no rules on the actual drone, unlike the rigorous requirements the FAA places on manned airplane manufacturers.

“Certainly a great distinction can be drawn between that and manned aircraft,” Proudlove said.

“You can go onto the internet, spend $800 and two days later a drone turns up on your doorstep that has no federal oversight whatsoever. Moreover, you can go off and operate it commercially and for recreation.”

It’s an interesting dilemma for insurers who have to consider the safety of the drone in the absence of any federal oversight. If just one commercial drone crosses into the path of an airliner, the collision damage could exceed $10 million, not to mention the potential loss of lives.

“I see a lot of people missing a lot of steps and this is where insurance is really important,” said Perlman of UAV Coach.

“You can go onto the internet, spend $800 and two days later a drone turns up on your doorstep that has no federal oversight whatsoever. Moreover, you can go off and operate it commercially and for recreation.” — Christopher Proudlove, SVP, Global Aerospace.

Far too often, he said, people watch a “cool video on YouTube and think they can buy a drone, get unmanned pilot certified, and instantly have a profitable business.”

“There’s a lot of work to do,” he said.

“That’s where the industry is now; helping to facilitate that path for drone pilots,” Perlman said, noting that his drone insurance guide is the most popular page on his website.

Insurers routinely mandate higher safety standards than those set by the FAA for traditional aviation risks, Global Aerospace said in a report. Merely meeting the legal safety requirements to become a pilot may not be enough to guarantee that a new operator will be a safe operator.

“The minimum FAA standard is a great starting point and new commercial operators may need additional training to be proficient and safe,” said James Van Meter, an aviation practice leader at AGCS who helped to write the AGCS study.

“We are used to dealing with certificated pilots, certificated aircraft, a different level of sophistication and sort of a shared fate; if we insure a pilot in an airplane, his fate is in his own hands when he’s operating his own aircraft.”

With drone use, the pilot may be minimally trained and newly certificated, and operating equipment that cost under $1,000, so “there’s no shared fate,” Van Meter said.

“There are some challenges there, but the new regulation provides good basic training on air space, risk management and some introductory safety issues,” he said.

Alexander Sheard co-founded Skyvuze Technologies LLC, a brokerage specializing in drone insurance, after he had trouble figuring out how to insure the drones he used in an aerial photography business.

Sheard said Skyvuze bridges the gap between drone entrepreneurs and the underwriters that offer unmanned aviation policies. He helps other drone pilots figure out what insurance they need and additional safety measures they should take.

“It’s really looking at all the risk and exposure and coming up with a complete package for these new operators that are popping up every day,” Sheard said.

Any commercial drone operator should assume that their customers and partners will eventually require them to certify that they are insured, Sheard said. Many experts also expect to one day see a type of vehicle registration similar to that required on cars.

“The ones that recognize there are risks as a key part of their business every time they bring this bird up into the sky, those are the ones that are going to be successful,” Perlman said.

“Those are the ones insurance companies are going to want to work with because they are mitigating their risks anyway and they have a ‘safety first’ mind-set.”

“We don’t yet truly understand the hazards, we don’t understand the capabilities of the system, how long they’ll last, what type of experience an operator needs to safely operate a certain make and model of drone,” Proudlove said.

“We are learning all this as we go. It’s really unbelievable what we are going to see over the next couple of years as far as the drone pilots and continued innovations,” Perlman said.

“That’s really exciting but I’m worried for that one operator who loses control for whatever reason and, maybe it’s cynical, but these things are dangerous.” &